Ancient Egyptian Embalming Residues Analyzed

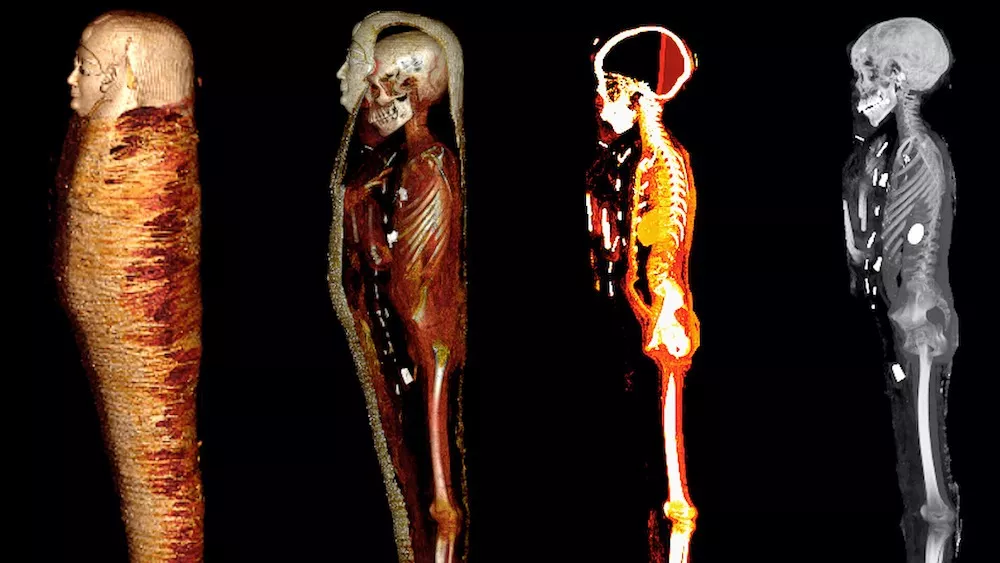

Scientists have unwrapped long-sought details of embalming practices that ancient Egyptians used to preserve dead bodies.

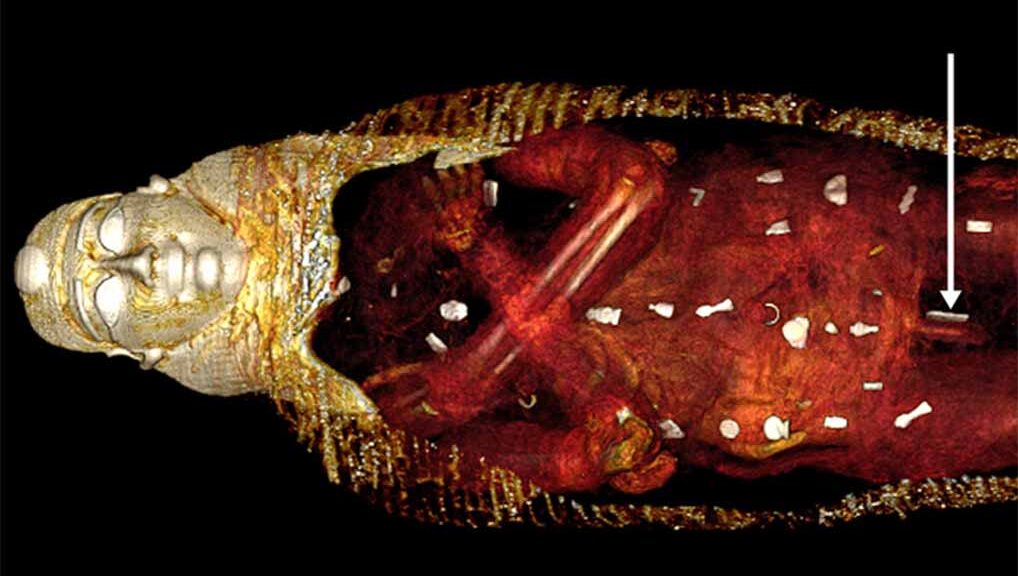

Clues came from analyses of chemical residue inside vessels from the only known Egyptian embalming workshop and nearby burial chambers. Mummification specialists who worked there concocted specific mixtures to embalm the head, wash the body, treat the liver and stomach, and prepare bandages that swathed the body, researchers report February 1 in Nature.

“Ancient Egyptian embalmers had extensive chemical knowledge and knew what substances to put on the skin to preserve it, even without knowing about bacteria and other microorganisms,” Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, said at a January 31 news conference.

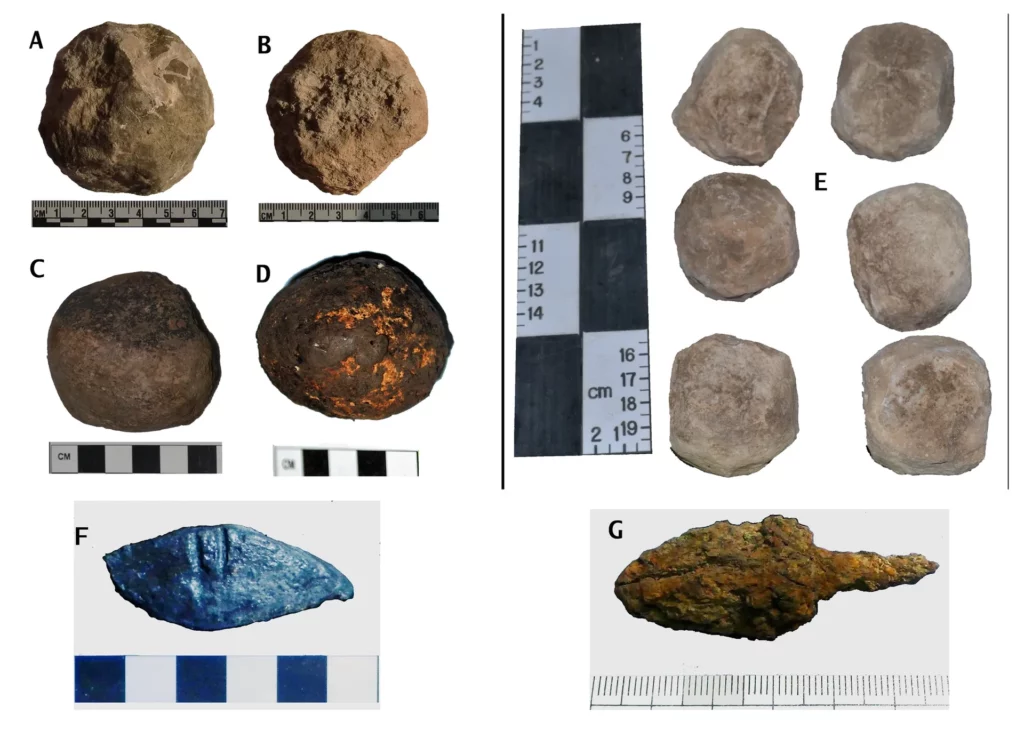

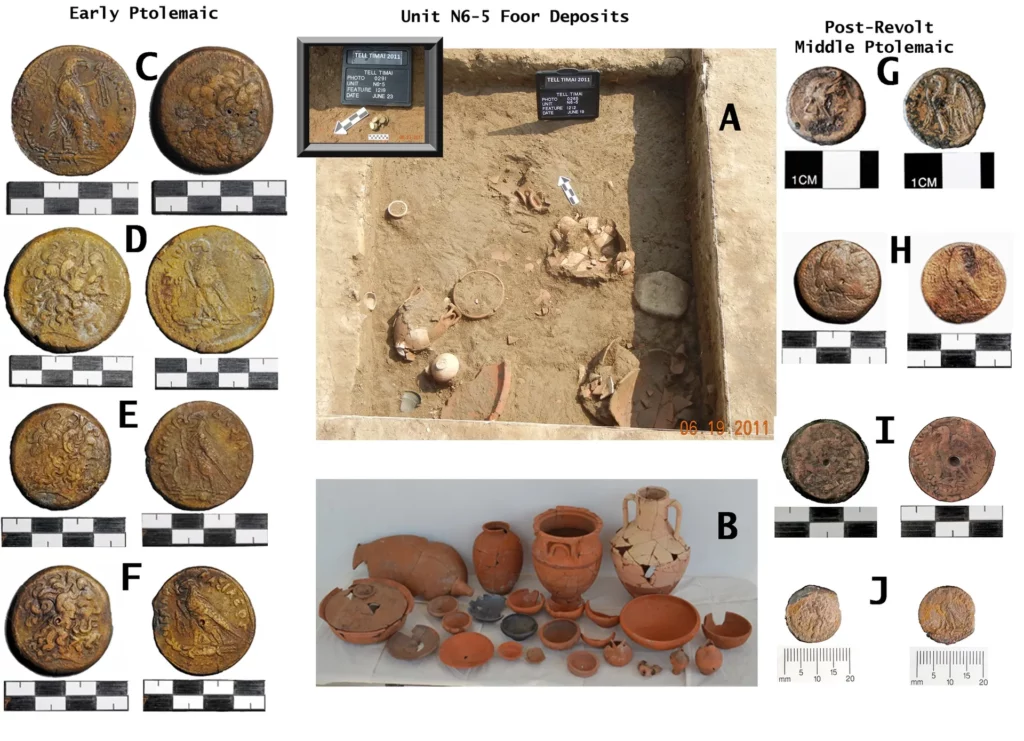

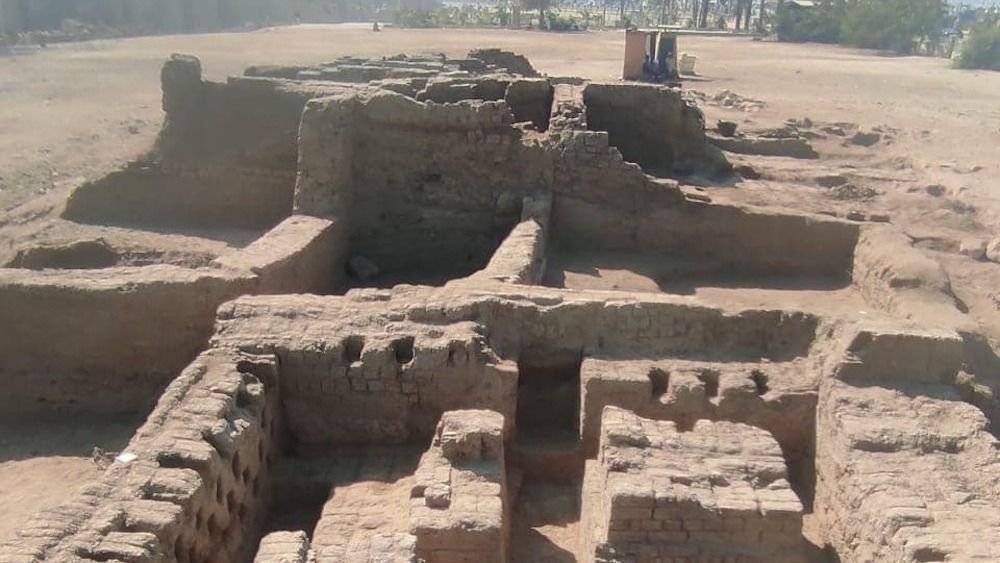

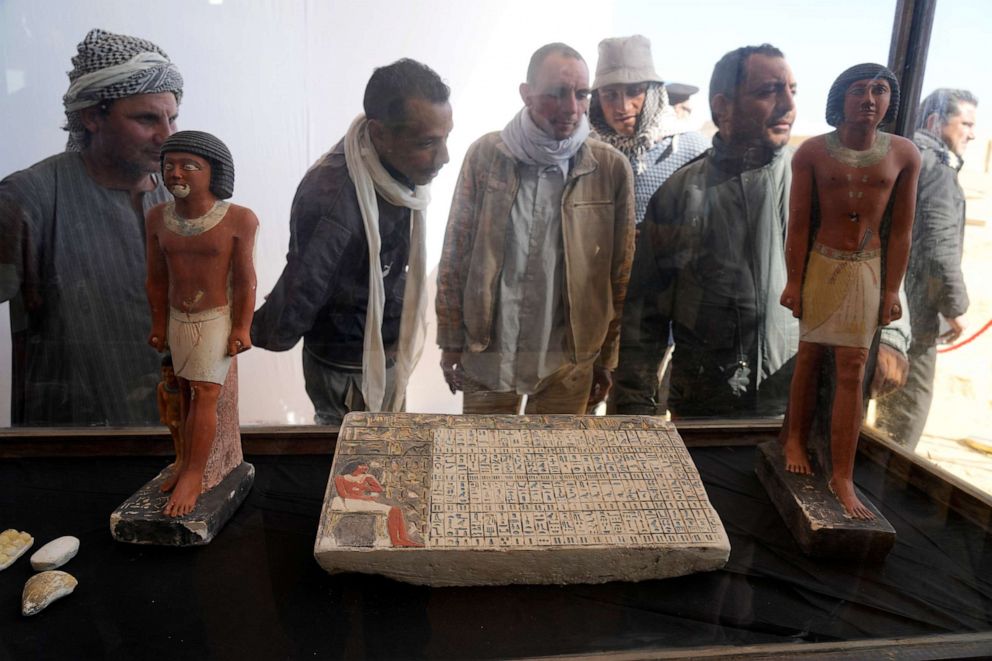

The findings come courtesy of chemical residue inside 31 vessels found in an Egyptian embalming workshop and four vessels discovered in an adjacent pair of burial chambers. Writing on workshop vessels named embalming substances, provided embalming instructions (such as “to put on his head”) or both. All the artifacts — dating from Egypt’s 26th dynasty which rose to power between 664 B.C. and 525 B.C. — were excavated at a cemetery site called Saqqara in 2016. Archaeologist and study coauthor Ramadan Hussein, who died in 2022, led that project.

Newfound mummy embalming mixtures

Five of the vessels had the label antiu. The substance was thought to have been a fragrant resin called myrrh. The antiu at Saqqara, however, consisted of oil or tar from cedar and juniper or cypress trees mixed with animal fats. Writing on these jars indicates that antiu could have been used alone or combined with another substance called sefet.

Three vessels from the embalming workshop bore the label sefet, which researchers have usually described as an unidentified oil. At Saqqara, sefet was a scented, fat-based ointment with added ingredients from plants. Two sefet pots contained animal fats mixed with oil or tar from juniper or cypress trees. A third container held animal fats and elemi, a fragrant resin from tropical trees.

Clarification of the ingredients in antiu and sefet at Saqqara “takes mummification studies further than before,” says Egyptologist Bob Brier of Long Island University in Brookville, N.Y., who was not part of the research.

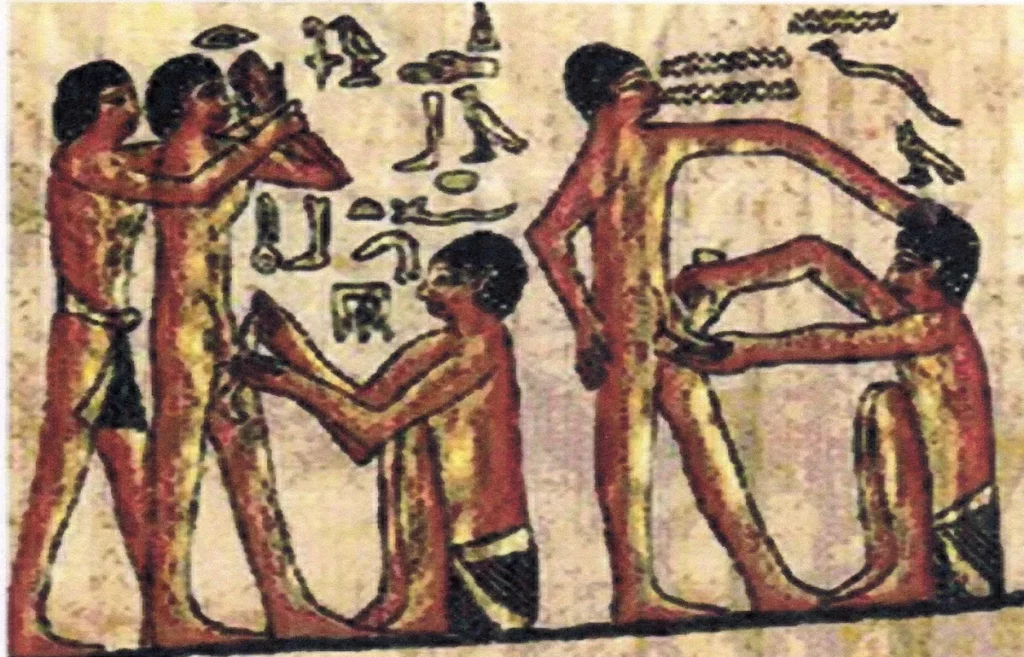

Egyptians may have started mummifying their dead as early as 6,330 years ago (SN: 8/18/14). Mummification procedures and rituals focused on keeping the body fresh so the deceased could enter what was believed to be an eternal afterlife.

Embalming and mummification procedures likely changed over time, says team member Maxime Rageot, a biomolecular archaeologist also at Ludwig Maximilians University. Embalmers’ mixtures at Saqqara may not correspond, say, to those used around 700 years earlier for King Tutankhamun (SN: 11/2/22).

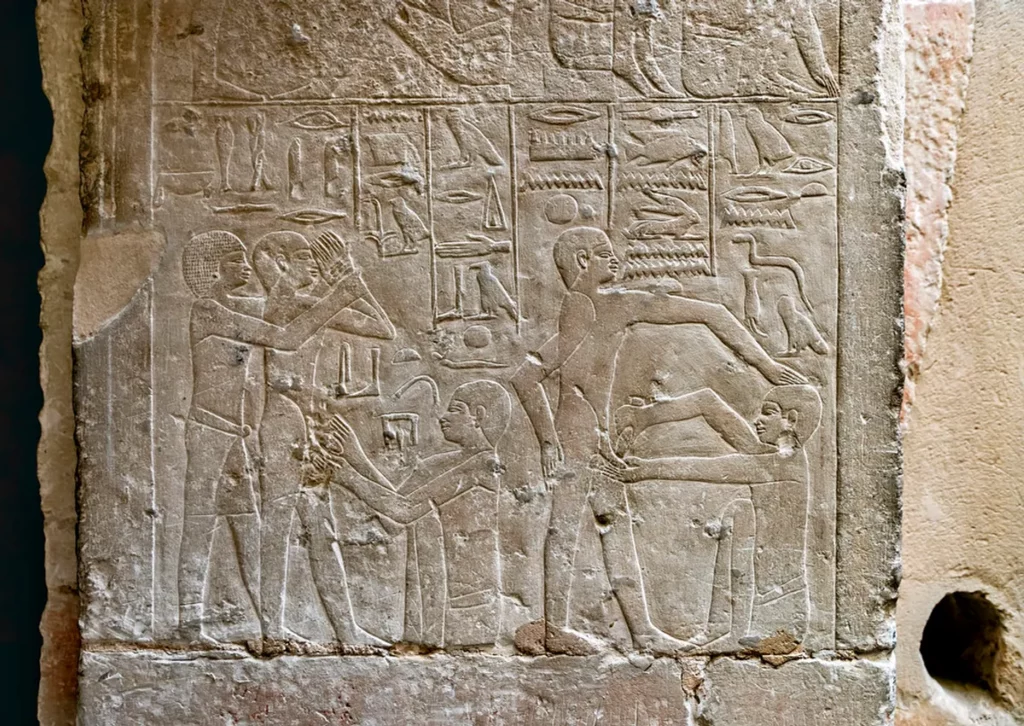

Mummy embalming instructions

Outside surfaces of other vessels from the Saqqara embalming workshop and burial chambers sported labels and, in some cases, instructions for treatment of the head, preparation of linen mummy bandages, washing the body and treating the liver and stomach. Inscriptions on one jar referred to an administrator who performed embalming procedures, mainly on the head.

Chemical residue inside these pots consisted of mixtures specific to each embalming procedure. Ingredients included oils or tars of cedar and juniper or cypress trees, pistachio resin, castor oil, animal fats, heated beeswax, bitumen (a dense, oily substance), elemi and a resin called dammar.

Most of those substances have been identified in earlier studies of chemical residues from Egyptian mummies and embalming vessels in individual tombs, says Egyptologist Margaret Serpico of University College London. But elemi and dammar resins have not previously been linked to ancient Egyptian embalming practices and are “highly unexpected,” notes Serpico, who did not participate in the new study.

Elemi was an ingredient in the workshop mixtures used to treat the head, the liver and bandages wrapped around the body. Chemical signs of dammar appeared in a vessel from one of the burial chambers that included remnants of a range of substances, indicating that the container had been used to blend several different mixtures, the researchers say.

Specific properties of elemi and dammar that aided in preserving dead bodies have yet to be investigated, Stockhammer said.

A far-flung trade network for mummy embalming ingredients

Elemi resin reached Egypt from tropical parts of Africa or Southeast Asia, while dammar originated in Southeast Asia or Indonesia, Rageot says. Other embalming substances detected at Saqqara came from Southwest Asia and parts of southern Europe and northern Africa bordering the Mediterranean Sea. These findings provide the first evidence that ancient Egyptian embalmers depended on substances transported across vast trade networks.

Egyptian embalmers at Saqqara took advantage of a trade network that already connected Egypt to sites in Southeast Asia, Stockhammer said. Other Mediterranean and Asian societies also engaged in long-distance trade during ancient Egypt’s heyday (SN: 1/9/23).

It’s no surprise that ancient Egyptians imported embalming ingredients from distant lands, Brier says. “They were great traders, had limited [local] wood products and really wanted these substances to achieve immortality.”