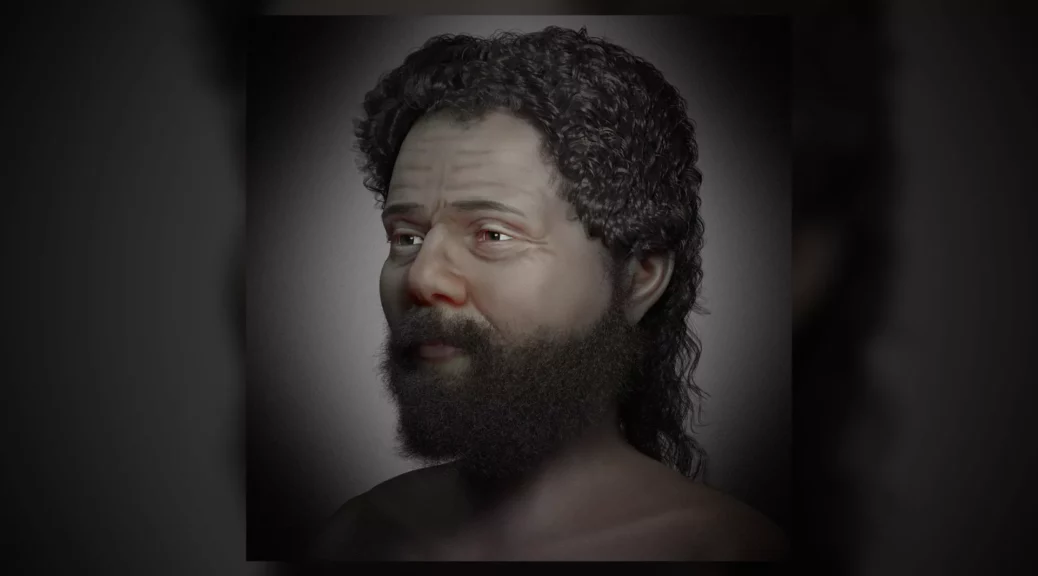

Digital Reconstruction Depicts Face of “Jericho Skull”

A famous, 9,000-year-old human skull discovered near the biblical city of Jericho now has a new face, thanks to efforts by a multi-national team of researchers.

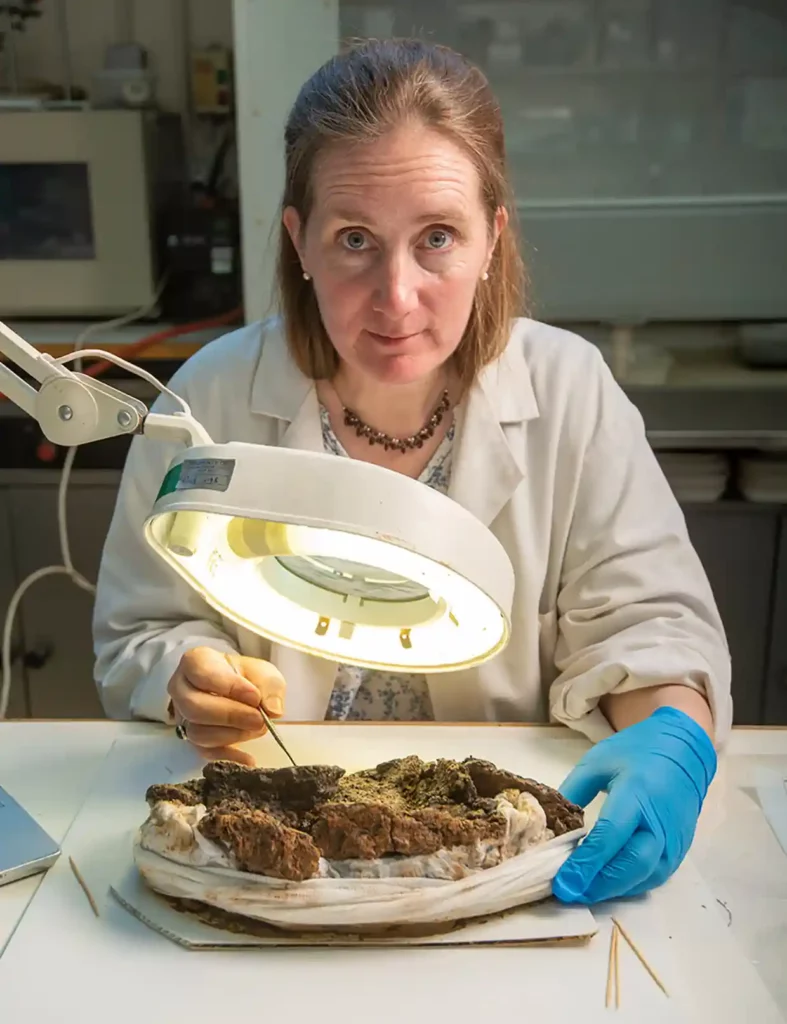

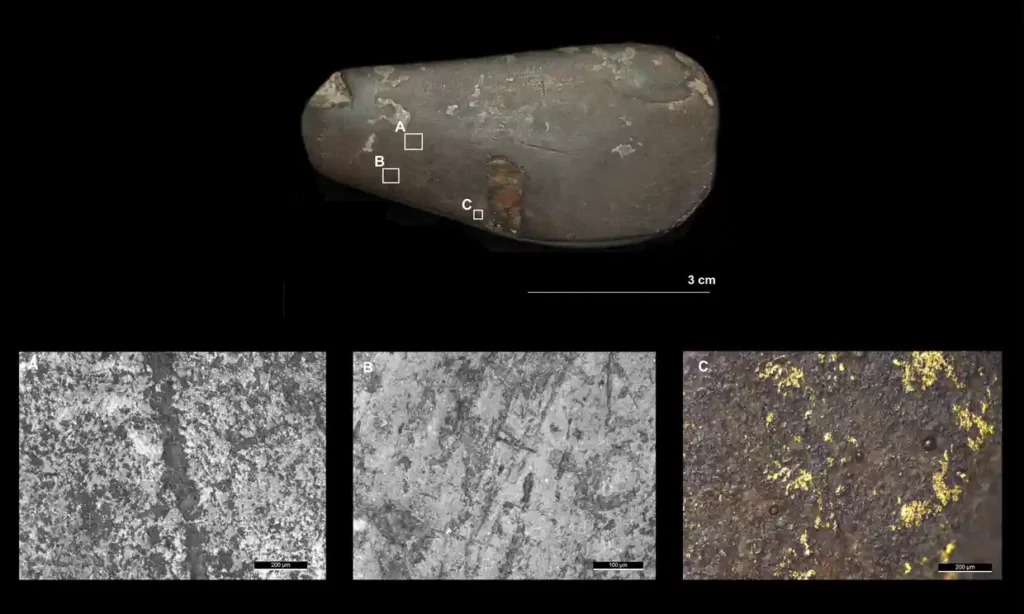

The so-called Jericho Skull — one of seven unearthed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon in 1953 and currently housed in the British Museum in London — was found covered in plaster and with shells for eyes, apparently in an attempt to make it look more lifelike.

This prehistoric design was “the first facial reconstruction in the world,” Brazilian graphics expert Cícero Moraes, the leader of the project, told Live Science in an email.

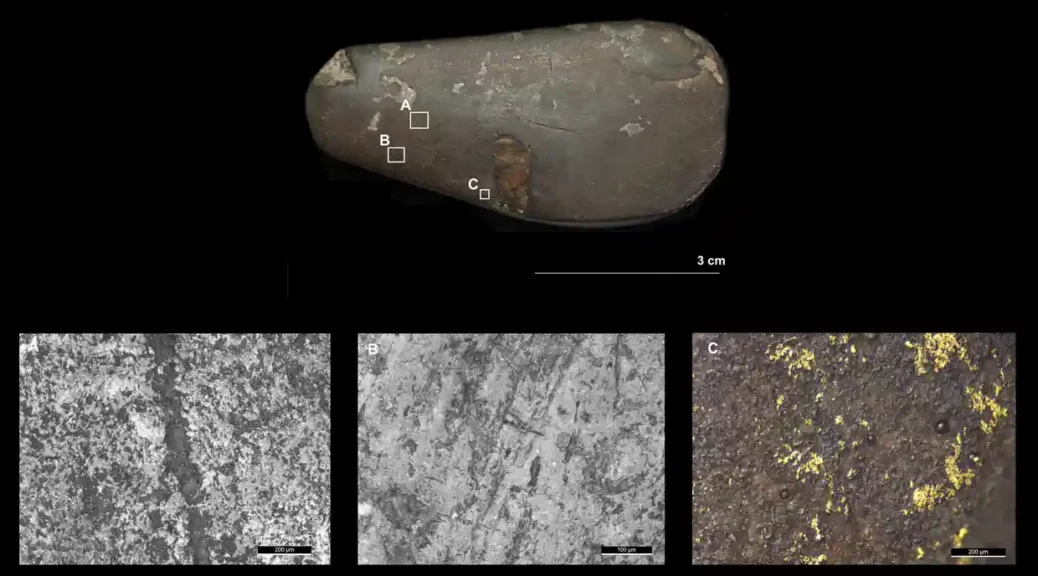

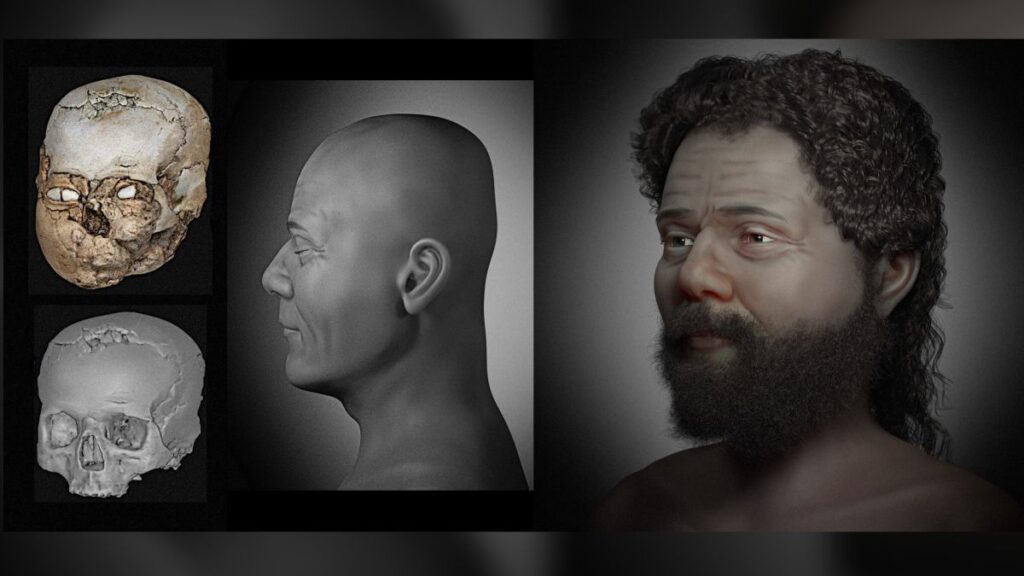

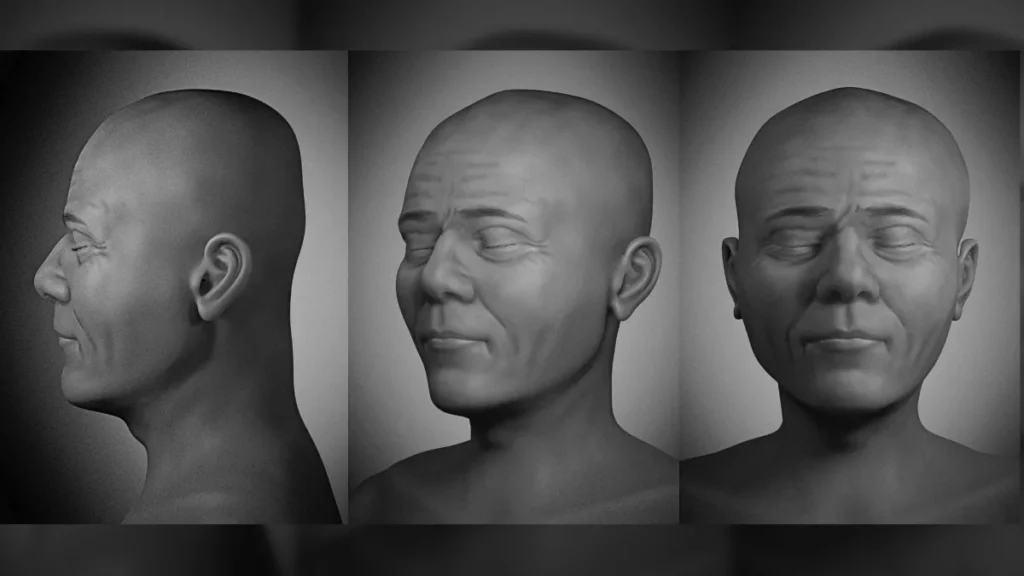

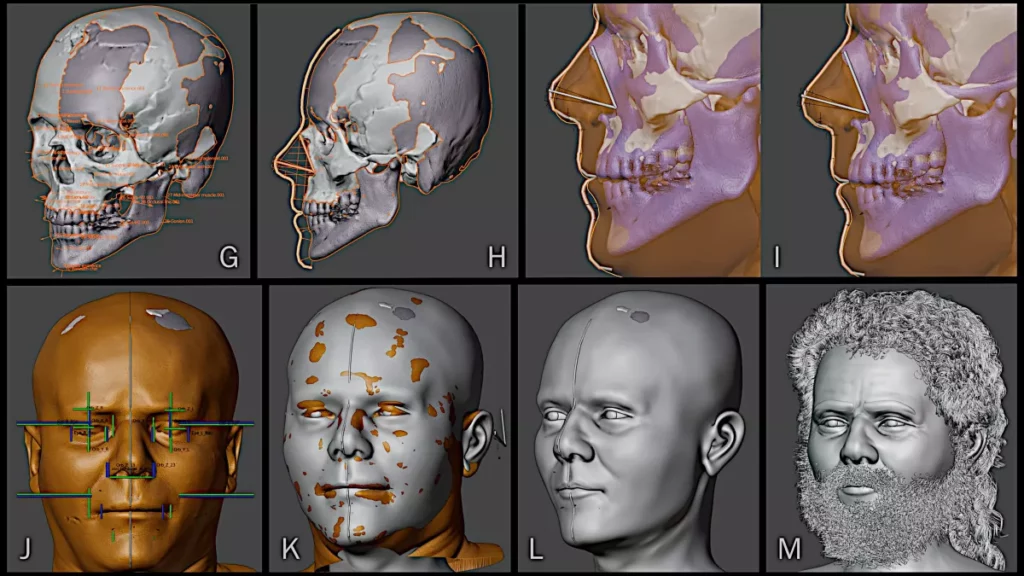

In 2016, the British Museum released precise measurements of the Jericho Skull, based on a micro-computed tomography, or micro-CT — effectively a very detailed X-ray scan. The measurements were then used to create a virtual 3D model of the skull, and the model was used to make an initial facial approximation.

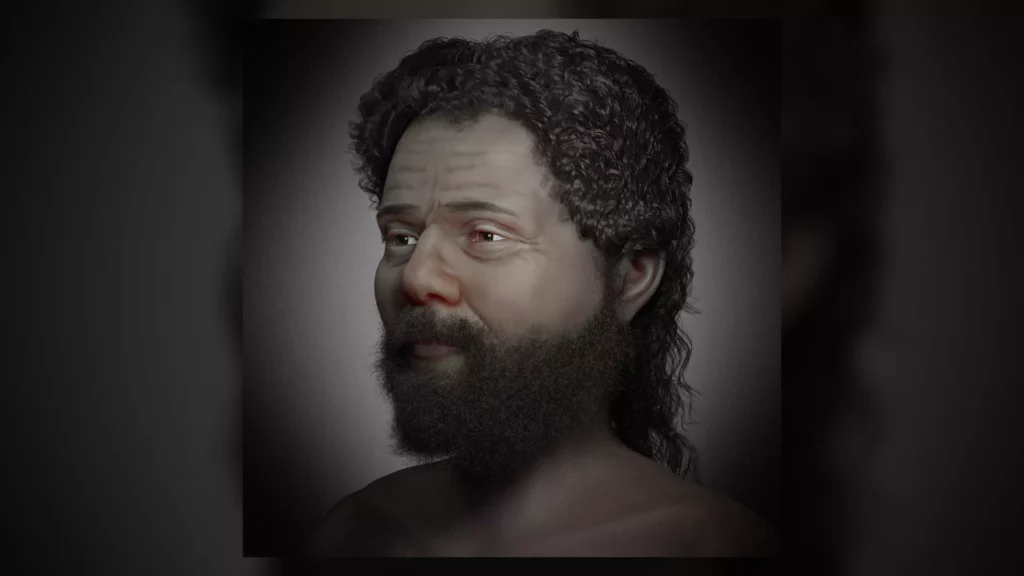

But the new approximation, published online on Dec. 22 in the journal OrtogOnline, uses different techniques to determine how the face may have looked, and goes further by artistically adding head and facial hair.

Although the skull was initially thought to be female, later observations determined it belonged to a male individual, Moraes said, so the new approximation shows the face of a dark-haired man in his 30s or 40s. (Based on how a lesion on the skull has healed, archaeologists suggest he was “middle-aged” by today’s standards when he died.)

An unusual feature of the British Museum’s Jericho Skull is that the cranium, or upper skull, is significantly larger than average, Moraes said.

In addition, the skull seems to have been artificially elongated when the man was very young, probably by tightly binding it; some of the other plastered skulls found by Kenyon also show signs of this, but the reason isn’t known.

Jericho skulls

Jericho, now a Palestinian city in the West Bank, is thought to be one of the oldest settlements in the world.

It appears in the biblical Book of Joshua as the first Canaanite city attacked by the Israelites after they crossed the Jordan River in about 1400 B.C. According to the biblical story, Jericho’s walls collapsed after Joshua ordered the Israelites to circle the city for seven days while carrying the Ark of the Covenant, and then to blow their trumpets and shout.

But archaeological research has failed to find any evidence of this event, and it’s now thought to be Judean propaganda, according to historians writing in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (Eerdmans, 2000).

Archaeologists have determined, however, that Jericho has been continually inhabited for about 11,000 years; and in 1953 Kenyon excavated seven skulls at a site near the ancient city.

Each had been encased in plaster, and the spaces inside the skulls were packed with earth. They also had cowrie seashells placed over their eye sockets, and some had traces of brown paint.

Kenyon speculated that the skulls might be portraits of some of Jericho’s earliest inhabitants; but more than 50 plastered skulls from about the same period have since been found throughout the region, and it’s now thought they are relics of a funerary practice, according to a study by Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a professor emerita of Art and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

New approximation

Moraes said he’s been unable to find many details of the 2016 facial approximation, but it seems to have used what’s known as the Manchester method, which has been developed since 1977 and is based on forensic analyses.

It is now widely used for facial approximations, especially of the victims of crimes.

The latest approximation, however, used a different approach, which is based on anatomical deformation and statistical projections derived from computed tomography (CT) scans— thousands of X-ray scans knitted together to create a 3D image — of living people, he said.

The techniques are also used to plan plastic surgeries and in the manufacturing of prostheses (artificial body parts), but neither were used in the 2016 study, he said.

“I wouldn’t say ours is an update, it’s just a different approach,” he said. But “there is greater structural, anatomical and statistical coherence.”

Moraes hopes to carry out digital approximations of other plastered skulls from the region, but so far only the precise measurements of the Jericho Skull in the British Museum have been published. “There is a lot of mystery around this material,” Moraes said. “Thanks to new technologies we are discovering new things about the pieces, but there is still a lot to be studied.”