Excavation Unearths Traces of 16th-Century Mansion in England

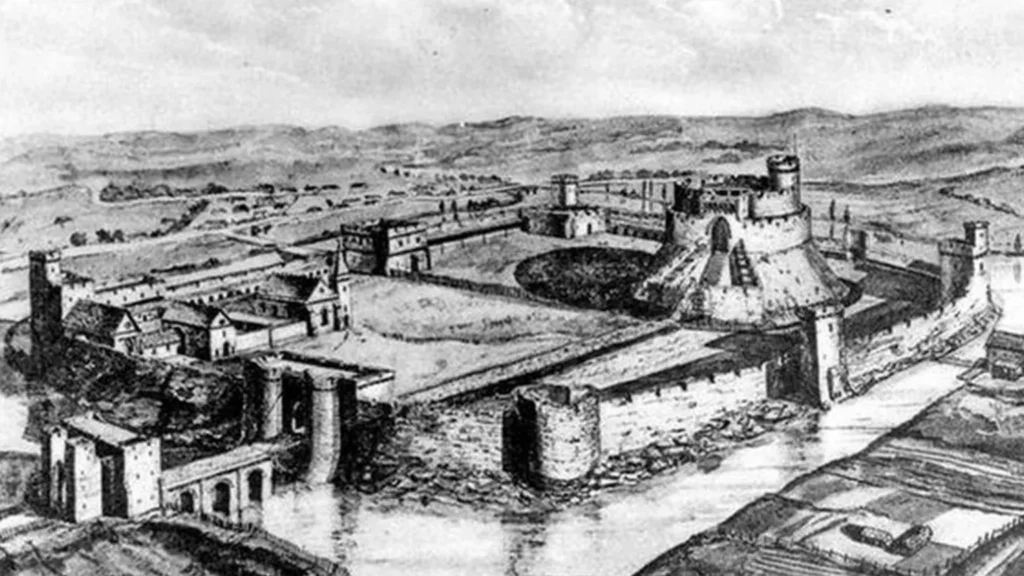

Excavations undertaken by Warwickshire’s Wessex Archaeology have discovered one of the UK’s best-preserved late 16th century gardens ever discovered.Archaeological investigations have revealed the remains of Coleshill Manor and an octagonal moat, aspects initially spotted by aerial drone images.

As excavations progressed, the remains of a massive garden dating from the very early 17th century were discovered, alongside the manor house.

Experts now believe after marrying an Irish heiress, owner Sir Robert Digby built his home in the modern style, in addition to lavish formal gardens measuring 300m (1km) from end to end, to flaunt his new-acquired wealth and consequent social status.

The hitherto-unknown gardens have been exceptionally well-preserved, and include gravel paths, planting beds, garden pavilion foundations and ornaments organised in an innovative geometric layout.

HS2’s Historic Environment Manager Jon Millward said the site has parallels to the iconic ornamental gardens at Kenilworth Castle and Hampton Court Palace.

He said in a statement: “It’s fantastic to see HS2’s huge archaeology programme making another major contribution to our understanding of British history.

“This is an incredibly exciting site, and the team has made some important new discoveries that unlock more of Britain’s past.”

Wessex Archaeology’s Project Officer, Stuart Pierson described the discovery as a career-high.

He said: “For the dedicated fieldwork team working on this site, it’s a once in a career opportunity to work on such an extensive garden and manor site, which spans 500 years.

“Evidence of expansive formal gardens of national significance and hints of connections to Elizabeth I and the civil war provide us with a fascinating insight into the importance of Coleshill and its surrounding landscape.

“From our original trench evaluation work, we knew there were gardens, but we had no idea how extensive the site would be.

“As work has progressed, it’s been particularly interesting to discover how the gardens have been changed and adapted over time with different styles.

“We’ve also uncovered structures such as pavilions and some exceptional artefacts including smoking pipes, coins and musket balls, giving us an insight into the lives of people who lived here.

“The preservation of the gardens is unparalleled.

“We’ve had a big team of up to 35 archaeologists working on this site over the last two years conducting trench evaluations, geophysical work and drone surveys as well as the archaeological excavations.”

Excavations have also revealed structures believed to date back to the late medieval period.

This includes structural evidence attributed to the large gatehouse in the forecourt of the Hall with its style and size alluding to a possible 14th or 15th century.

Dr Paul Stamper, a specialist in English gardens and landscape history, believes that, as a whole, the site is of the utmost archaeological importance.

He said: “This is one of the most exciting Elizabethan gardens that’s ever been discovered in this country.

“The scale of preservation at this site is really exceptional and is adding considerably to our knowledge of English gardens around 1600.

“There have only been three or four investigations of gardens of this scale over the last 30 years, including Hampton Court, Kirby in Northamptonshire and Kenilworth Castle, but this one was entirely unknown.

“The garden doesn’t appear in historical records, there are no plans of it, it’s not mentioned in any letters or visitors’ accounts.

“The form of the gardens suggest they were designed around 1600, which fits in exactly with the documentary evidence we have about the Digby family that lived here.

“Sir Robert Digby married an Irish heiress, raising him to the ranks of the aristocracy.

“We suspect he rebuilt his house and laid out the huge formal gardens measuring 300 metres from end to end, signifying his wealth.”