London’s largest Roman mosaic in 50 years discovered by archaeologists

In the shadow of the iconic Shard in London, archaeologists have come across an echo of the city’s ancient past. Right there in the heart of the city, they’ve unearthed a striking Roman mosaic that dates back to the late second or early third century.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime find in London,” raved Antonietta Lerz, the Museum of London Archeology (MOLA) site supervisor.

MOLA archaeologists uncovered the mosaic while excavating a new housing and retail development at the Liberty of Southwark site near the London Bridge. As they sifted through the dirt, something suddenly caught their attention.

“When the first flashes of colour started to emerge through the soil everyone on site was very excited,” Lerz explained.

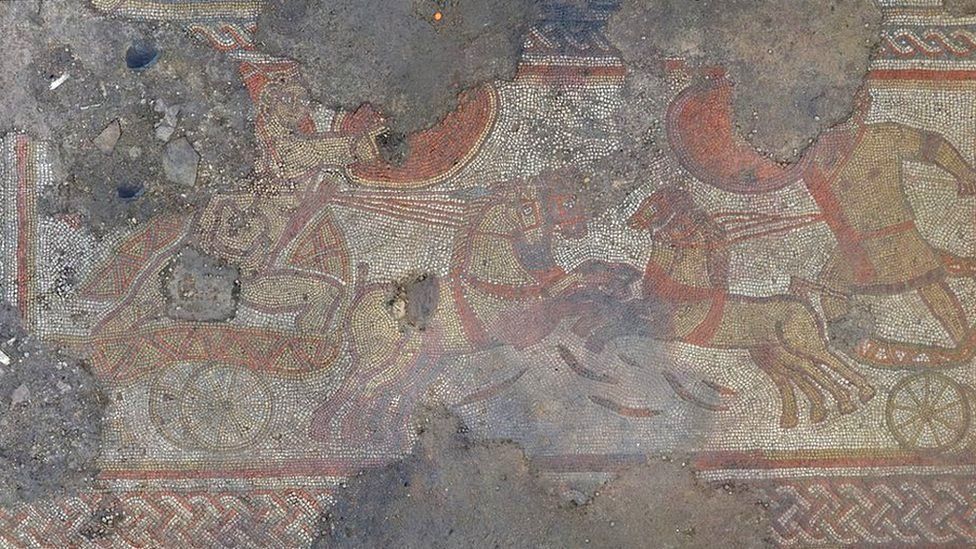

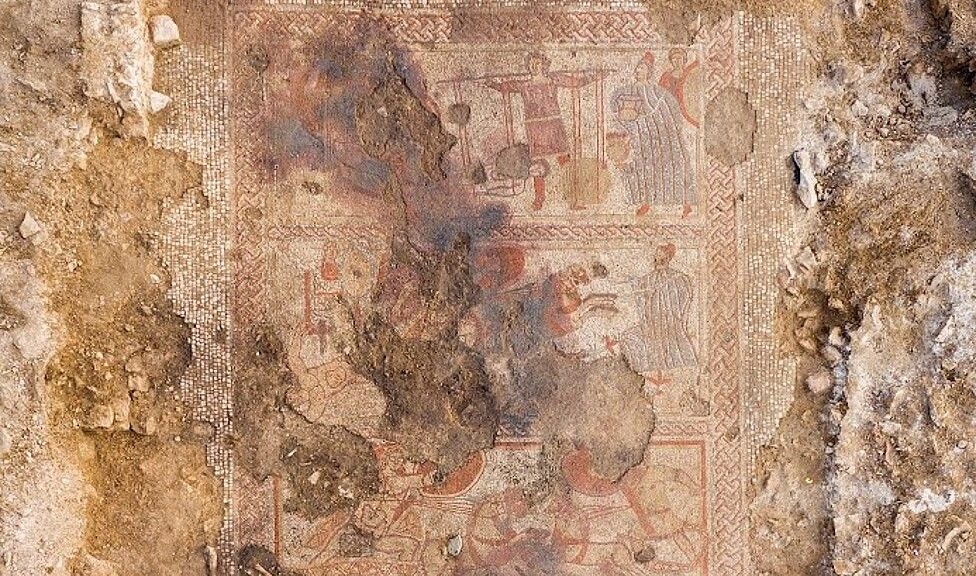

The archaeologists eventually uncovered a Roman mosaic made of two panels that stretches for more than 26 feet. The larger panel includes lotus flowers, a “Solomon’s knot” pattern, and intertwining strands called guilloche. The smaller panel is simpler but includes some of the same designs with red and black tiles. Historians have seen similar mosaics elsewhere.

David Neal, a Roman mosaic expert, believes that the larger panel was made by the Acanthus group, who developed a unique style in London. And, intriguingly, the smaller panel bears a striking resemblance to one found in Trier, Germany. That may mean that London artisans took their craft abroad.

Both mosaics probably made up a triclinium, a sort of formal dining room where upper-class ancient Romans would have lounged on couches, chatted, and admired the beautiful floor.

The triclinium itself likely made up one part of a mansio, a type of inn for Romans officials travelling on state business where they could rest, stable their horses, and get a bite to eat. Archaeologists suspect that it was part of a bigger complex, but they’re still examining the grounds.

Indeed, the mosaics weren’t the only discoveries that the MOLA archaeologists made. They also found evidence of a large building nearby, which may have been a wealthy Roman’s private house. There, they uncovered an intricate bronze brooch, a bone hairpin, and a sewing needle.

“These finds are associated with high-status women who were following the latest fashions and the latest hairstyles,” Lerz explained, noting that they lived during the “heydey of Roman London.”

“The buildings on this site were of very high status. The people living here were living the good life.”

Roman London, or Londinium, was first settled in 47 C.E. It expanded rapidly throughout the first century and reached its peak during the second century. At the time, Londinium boasted a population of around 45,000 to 60,000.

The largest city in Roman Britannia, it had a forum, a basilica, bathhouses, temples, and other features found in bustling Roman hubs. The mosaics found near The Shard are a striking throwback to that time.

“The Liberty of Southwark site has a rich history, but we never expected a find on this scale or significance,” explained Henrietta Nowne, a Senior Development Manager at regeneration specialist U+I, which is working with Transport for London to develop the Liberty of Southwark site.

“We are committed to celebrating the heritage of all of our regeneration sites, so it’s brilliant that we’ve been able to unearth a beautiful and culturally-important specimen in central London that will be now preserved so that it can be enjoyed by generations to come.”

Moving forward, Lerz and her team aim to preserve and display the stunning mosaics.

“Long term, we would hope to have these on public display and we are in consultation with Southwark Council to find an appropriate building to put them in, where they can be enjoyed by everyone,” she explained.

For now, the excavation of the Roman mosaics continues — just a three-minute walk from London’s gleaming Shard.