Victoria Cave: The underground Dales cavern that changed history

Victorian excavators were particularly fascinated by ‘bone caves’ where there might be a possibility of finding evidence for the earliest humans along with long-extinct animals.

The cavern near Settle is home to the skeletons of mammoths and Roman remains. Described as an ‘archaeologist’s dream’, Victoria Cave is made of limestone and can be found east of Langcliffe, in Ribblesdale.

It was discovered by chance in 1837 – the year Queen Victoria was crowned – and since then has yielded a number of incredible finds. It’s been completely excavated and has provided vital information about climate change over thousands of years.

An amazing discovery

A group of men from Settle was out walking their dogs in 1837 when one of them disappeared inside a foxhole. Its owner, Michael Horner, followed and found himself in a passage that led to a cave with Roman objects clearly visible on the ground.

He returned with his employer, Joseph Jackson, and the pair discovered a deeper chamber sealed from daylight. 20-year-old plumber Joseph had no knowledge of archaeology but began a large-scale candlelit excavation of the cave.

In 1840, he contacted Roman expert Charles Roach Smith, who visited the site just before Joseph dug up a hyena’s jawbone. A Victorian fascination with ‘bone caves’ soon developed, and the hunt for evidence of early man and the animals they had eaten began.

Charles Darwin himself even took an interest in Victoria Cave, and he became involved in another dig in 1870 that was linked to his emerging theories about human evolution. By this time, Joseph Jackson had become a full-time, eminent archaeologist.

Victoria Cave looked set to become a crucial archaeological and geological site – but two of the scientists involved later fell out over its contents.

The repercussions from the dispute, which centered around their conflicting views on cyclical climate change, led to Victoria Cave falling out of favor with the scientific community and it was gradually forgotten.

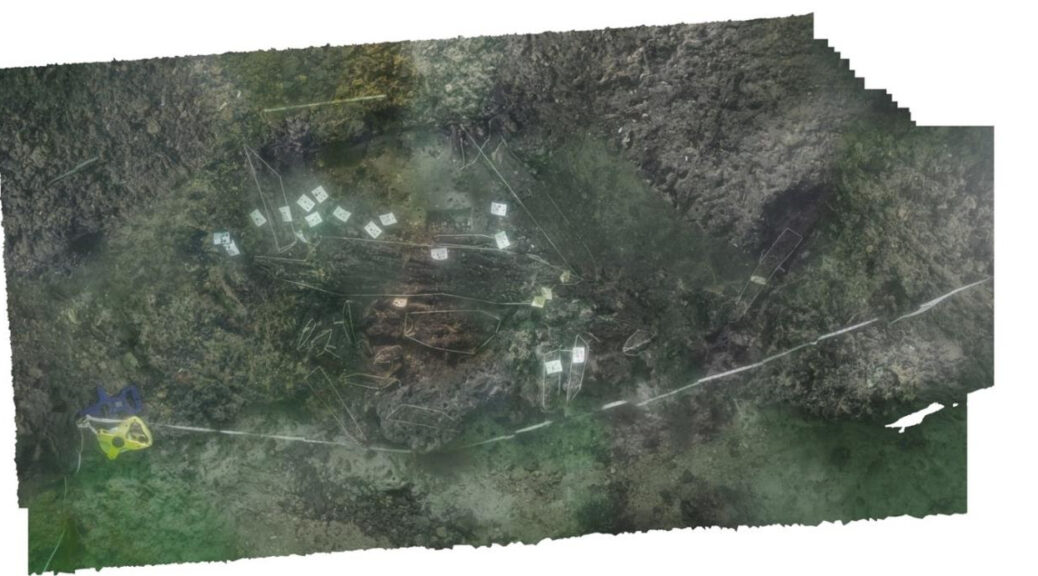

In the 1930s, the cave was re-discovered when a local greengrocer set up a society for cave explorers in his father’s pig yard. Tot Lord and his group collected as many of the artifacts as possible from the earlier digs and uncovered further remains.

His family has taken possession of the collection and archive material, and Victoria Cave returned to international prominence, with its importance highly valued. It offers the first proof that the Ice Age was cyclical and the final record of wild lynx living in Britain.

A prehistoric cache

Ancient bones found inside the cave, which is managed by the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority, include those of mammoths, hippos, rhino, elephants, and spotted hyenas who lived in the Dales over 130,000 years ago – when the climate was warm enough to support species that are nowadays more commonly found in Africa.

After the last Ice Age, evidence that a brown bear had hibernated in the cave was uncovered, and reindeer bones were found. One of the key discoveries was a key indicator of the first human life in the Dales – an 11,000-year-old antler harpoon point used for hunting the deer.

Roman remains

The area seems to have later been inhabited by the Romans – artifacts such as brooches, coins, and pottery from the period were buried in the cave, some of them imported from France and Africa.

Experts believe the cave could have been a religious shrine, with a workshop outside. Some of the items have been put on display at the Craven Museum in Skipton.

Access to the cave is limited as the roof is dangerously unstable, but walkers can visit the entrance.