Evidence of Europe’s first Homo sapiens was found in a French cave

Stone artefacts and tooth pre-date the earliest known evidence of the species in Europe by more than 10,000 years.

Archaeologists have found evidence that Europe’s first Homo sapiens lived briefly in a rock shelter in southern France — before mysteriously vanishing.

A study published on 9 February in Science Advances1 argues that distinctive stone tools and a lone child’s tooth were left by Homo sapiens during a short stay, some 54,000 years ago — and not by Neanderthals, who lived in the rock shelter for thousands of years before and after that time.

The Homo sapiens occupation, which researchers estimate lasted for just a few decades, pre-dates the previous earliest known evidence of the species in Europe by around 10,000 years.

But some researchers are not so sure that the stone tools or teeth were left by Homo sapiens. “I find the evidence less than convincing,” says William Banks, a paleolithic archaeologist at the French national research agency CNRS and the University of Bordeaux.

Tools, bones, and teeth

A team co-led by Ludovic Slimak, a cultural anthropologist at CNRS and the University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès, has spent the past three decades excavating the Grotte Mandrin rock shelter in the Rhône Valley.

The researchers have uncovered tens of thousands of stone tools and animal bones, as well as 9 hominin teeth, all dating from around 70,000 to 40,000 years ago.

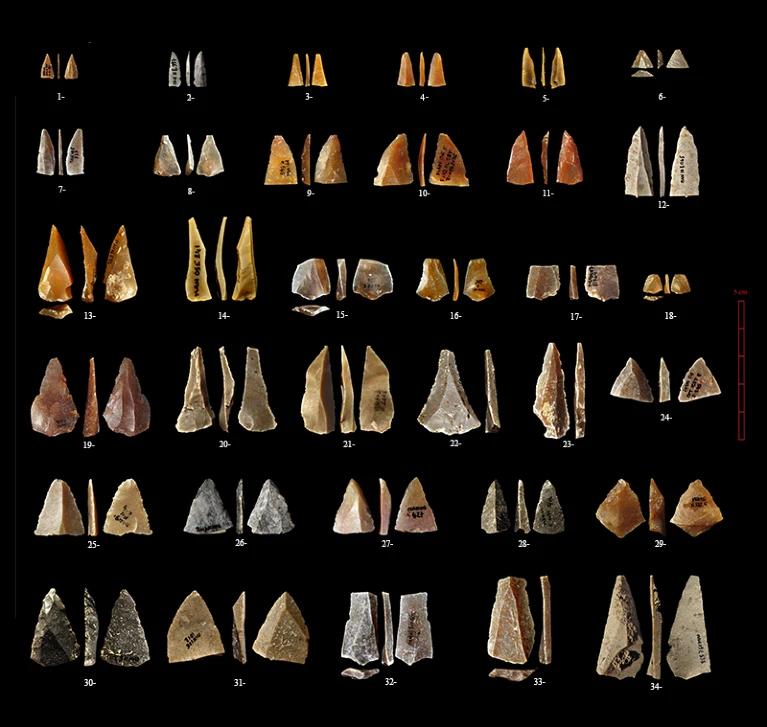

Most of the stone tools resemble artifacts categorized as ‘Mousterian technology’ that are found at Neanderthal sites across Eurasia, says Slimak. But one of the shelter’s archaeological levels — known as layer E and dated to between 56,800 and 51,700 years ago — contains tools such as sharpened points and small blades that are more typical of early Homo sapiens technology. Slimak says the layer E stone tools resemble those found at much younger sites in southern France, left by makers unknown, as well as those from similarly aged sites in the Middle East that are linked to Homo sapiens.

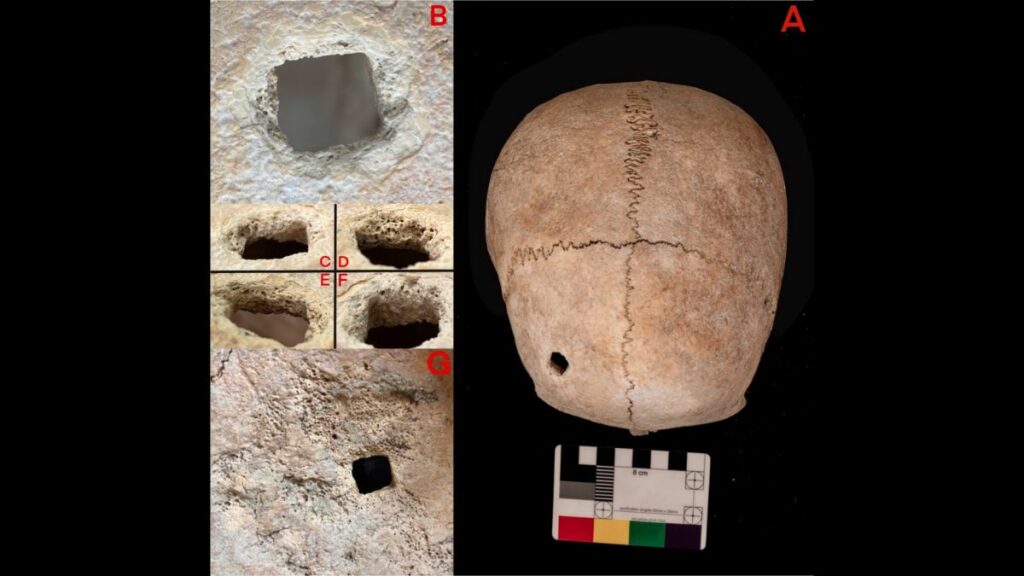

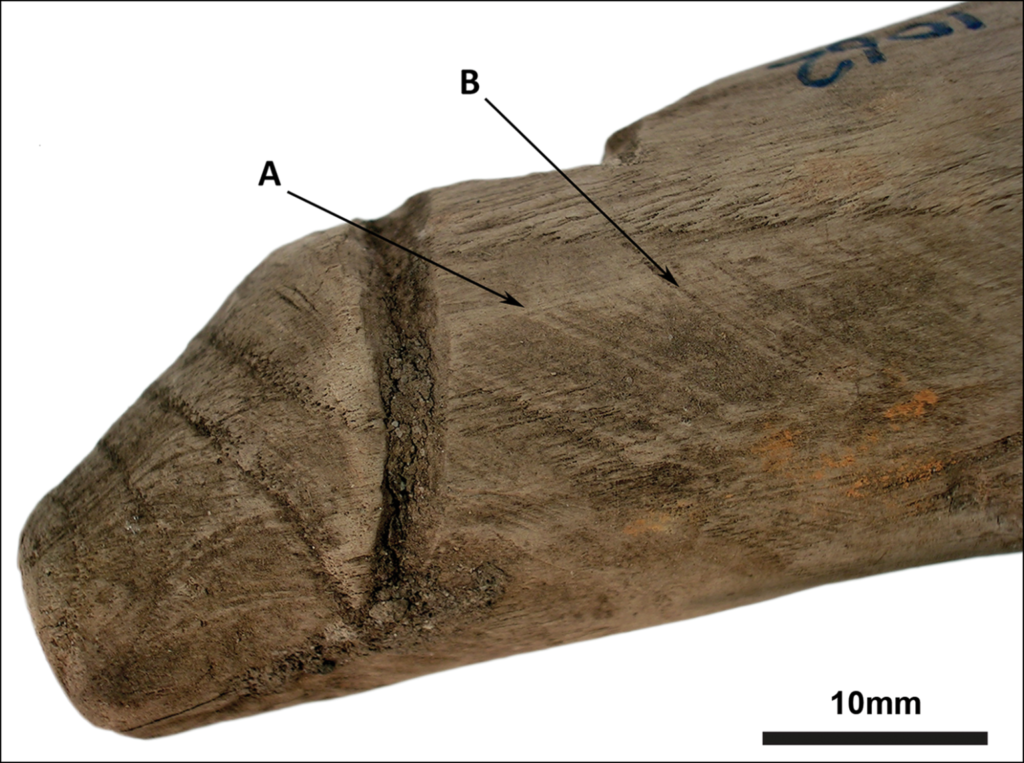

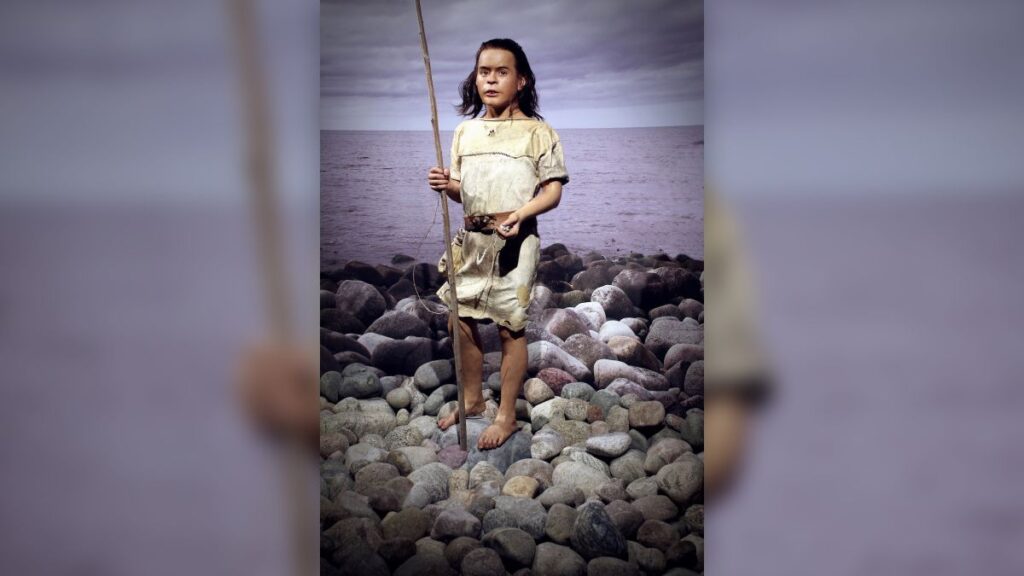

An analysis led by Clément Zanolli, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux who, found that the only hominin tooth in layer E, a molar probably from a child, is similar in shape to those of Homo sapiens who lived in Eurasia during the last Ice Age. Other teeth found in Grotte Mandrin resemble those of Neanderthals.

The researchers have not attempted to extract DNA from the layer E tooth to confirm whether it belongs to Homo sapiens or a Neanderthal.

Slimak says that in an unpublished analysis, other researchers have found Neanderthal DNA in sediments older than layer E, as well as in a tooth from Grotte Mandrin’s younger layers.

But the team was unable to extract much well-preserved DNA from horse teeth found in the rock shelter, including layer E. So they have decided to hold off on the destructive process of taking samples from the layer E hominin tooth until they have access to technology that will give them a good chance of getting genetic material out intact. “This tooth is very precious. There’s some chance there’s preserved DNA in it,” Slimak says.

If Homo sapiens left the tools and tooth in layer E, they weren’t in Grotte Mandrin for long. Slimak estimates that the residency lasted for around 40 years, on the basis of an analysis of fragments of the shelter’s ceiling that had broken off and been deposited alongside other archaeological material.

New layers of the white mineral calcite accrued on the ceiling twice each year, during wet periods, and soot from fires in the shelter left black marks, creating a sort of ‘barcode’ that can pinpoint hominin occupations to within a year. The researchers concluded that the last Homo sapiens fire went out no more than a year before the next Neanderthal one. “The populations must have in some way met each other,” Slimak adds. Yet the researchers found no obvious signs of cultural exchanges, such as similarities in stone tools, between the two groups.

Early settlers

If layer E was occupied by Homo sapiens, however fleetingly, it would put the species in Europe thousands of years earlier than other records suggest. The region’s oldest definitive Homo sapiens remains — confirmed with DNA — come from Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria, and are around 44,000 years old2.

“It is exciting to see that Homo sapiens was in western Europe several thousand years earlier than previously thought,” says Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands. “It shows that the peopling of Europe by Homo sapiens was likely a long and hazardous process.”

But Banks is not yet convinced that Grotte Mandrin was once home to Europe’s earliest known Homo sapiens. He says that the layer E tools are more likely to be local inventions than imports from people in the Middle East.

There can also be substantial overlap in the shapes of the teeth of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. “It is not a stretch to think that a single Neanderthal tooth could have dental characteristics that resemble moderns,” he says.