Why There Are Six Million Skeletons Stuffed Into The Tunnels Beneath Paris

One of his mysterious entrances into the French capital Paris should you be closely looking for. But if you trip over it, it shows a dark and dank and narrow tunnel underground world with a fascinating history.

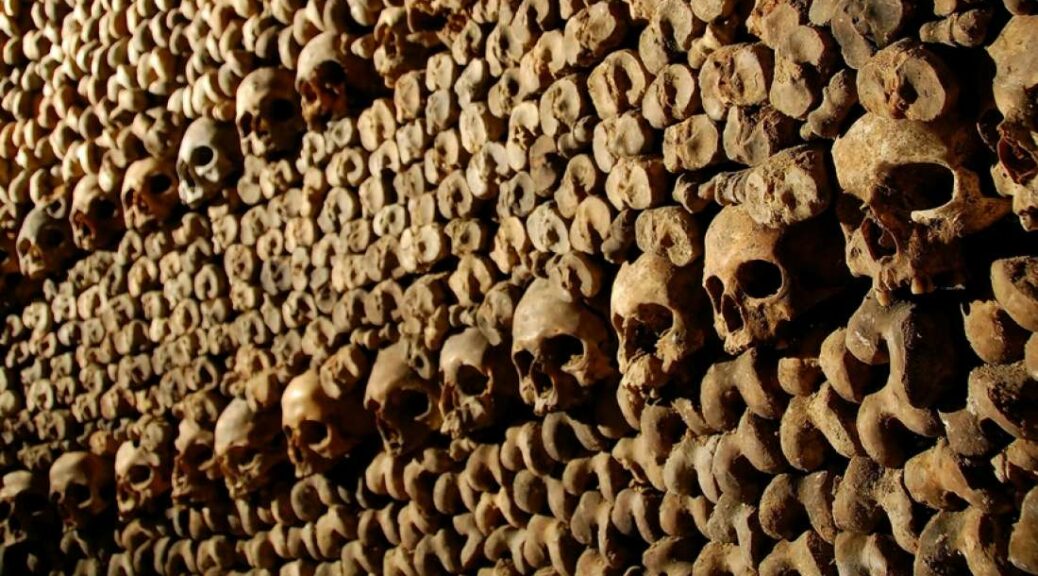

The bones of 6 million people known as the French Empire of the Dead a reality brought to life in the recent CNN movie-lie underneath the City of Light where 12 million people are living there.

The Paris catacombs are a 200-mile network of old caves, tunnels, and quarries – and much of it is filled with the skulls and bones of the dead.

Much of the catacombs are out of bounds to the public, making it illegal to explore unsupervised. But nevertheless, it is a powerful draw for a hardcore group of explorers with a thirst for adventure.

A tourist-friendly, the legal entrance can be found off Place Denfert-Rochereau in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, near the Montparnasse district.

Here, visitors from all over the world can descend into the city’s dark and dank bowels for a whistle-stop tour of a small section of the catacombs.

One visitor told CNN: ‘I think people are fascinated with death. They don’t know what it’s about and you see all these bones stacked up, and the people that have come before us, and it’s fascinating. We’re trying to find our past and it’s crazy and gruesome and fun all at the same time.’

The well-worn trail might be enough to satisfy the tourists, but other Parisians like to go further – and deeper – to explore the network. The name given to the group of explorers who go into the cave network illegally and unsupervised is Cataphiles.

The top-secret groups go deep underground, using hidden entrances all over the city. And they sometimes stay for days at a time, equipped with headlamps and home-made maps.

Street names are etched into the walls to help explorers navigate their way around the underground version of the city and some groups have even been known to throw parties in the tunnels or drink wine.

For catacomb devotees, the silence experienced deep in tunnels cannot be replicated anywhere else.

Urban explorer Loic Antoine-Gambeaud told CNN: ‘I think it’s in the collective imagination. Everybody knows that there is something below Paris; that something goes on that’s mysterious. But I don’t think many people have even an idea of what the underground is like.’

Those caught exploring unauthorized sections of the network could end up out of pocket. Police tasked with patrolling the tunnels have the power to hand out fines of 60 euros to anyone caught illegally roaming the network.

A by-product of the early development of Paris, the catacombs were subterranean quarries which were established as limestone was extracted deep underground to build the city above.

However, a number of streets collapsed as the quarries weakened parts of the city’s foundations. Repairs and reinforcements were made and the network went through several transformations throughout history.

However, it wasn’t until the 18th century that the catacombs became known as the Empire of the Dead when they became the solution to overcrowding in the city’s cemeteries.

The number of dead bodies buried in Paris’s cemeteries and beneath its churches was so great that they began breaking through the walls of people’s cellars and causing serious health concerns.

So the human remains were transferred to the underground quarries in the early 1780s. There are now more than 6million people underground.

Space was the perfect solution to ease overcrowding in cemeteries but it presented disadvantages elsewhere. It is the reason there are few tall buildings in Paris; large foundations cannot be built because the catacombs are directly under the city’s streets.

The tunnels also played their part in the Second World War. Parisian members of the French Resistance used the winding tunnels and German soldiers also set up an underground bunker in the catacombs, just below the 6th arrondissement.