This 48-Million-Year-Old Fossil Has an Insect Inside a Lizard Inside a Snake

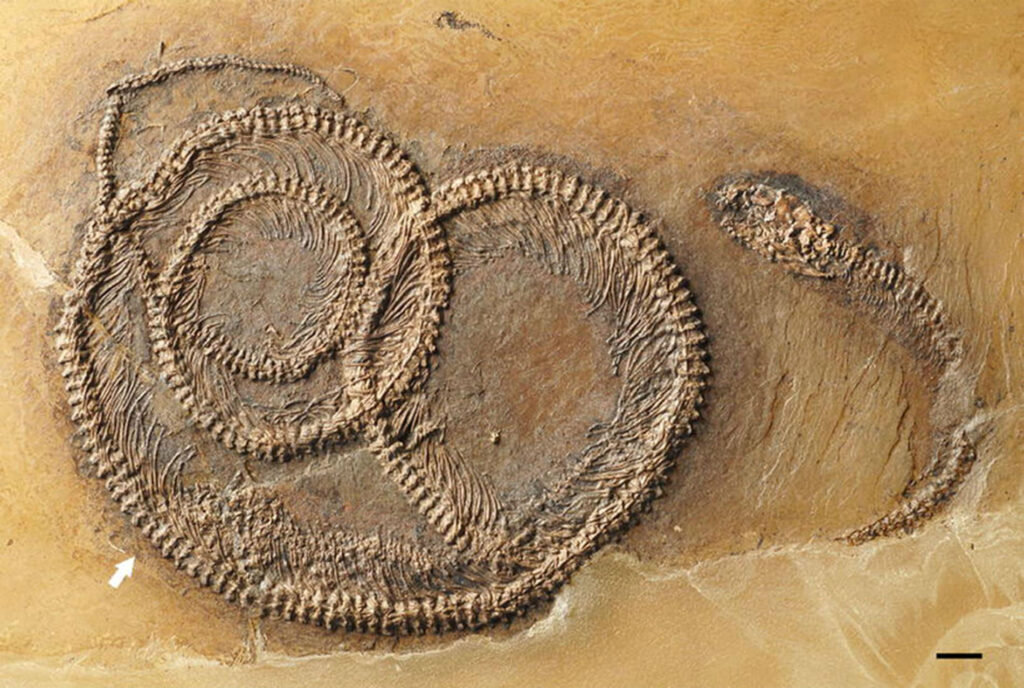

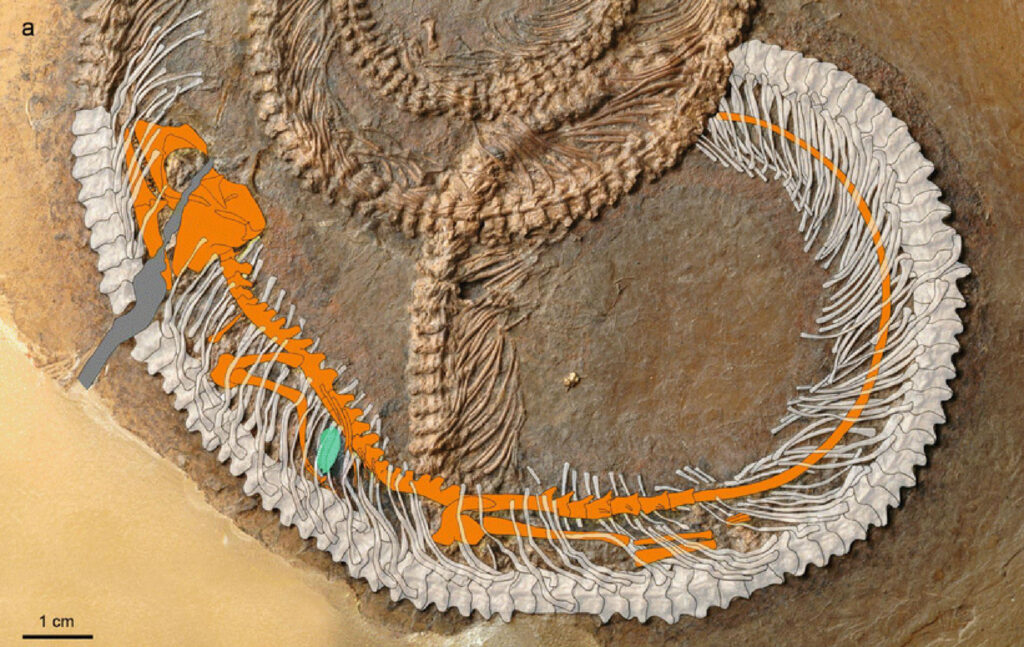

Palaeontologists have uncovered a fossil that has preserved an insect inside a lizard inside a snake – a prehistoric battle of the food chain that ended in a volcanic lake some 48 million years ago.

Pulled from an abandoned quarry in southwest Germany called the Messel Pit, the fossil is only the second of its kind ever found, with the remains of three animals sitting snug in one another.

“It’s probably the kind of fossil that I will go the rest of my professional life without ever encountering again, such is the rarity of these things,” palaeontologist Krister Smith from Germany’s Senckenberg Institute told Michael Greshko at National Geographic. “It was pure astonishment.”

Smith and his team suspect that the iguana ate a shiny insect meal, and then two days later was swallowed headfirst by a juvenile snake.

It’s unclear how the snake ultimately died, but what we do know is it got too close to the deep volcanic lake that once bubbled in the Messel Pit, and was either poisoned or suffocated by the toxic fumes.

Its corpse likely slid into the lake after death, where the Russian doll of skeletons was preserved perfectly for millions of years.

“To see this kind of trophic scale recorded within the gut of a snake is a very cool thing,” UK palaeontologist Jason Head from the University of Cambridge, who wasn’t involved with the study, told National Geographic.

While the combination of snake-lizard-bug is entirely unique in the fossil record, this isn’t the first time a prehistoric turducken has been discovered.

Back in 2008, Austrian researchers found a 250-million-year-old fossil that had preserved a shark that had eaten some kind of amphibian that had eaten a small fish.

It’s far more fragmentary than the Messel Pit fossil, but it was the first real indication that the food web of the time was far more complex than researchers had thought.

If anywhere is likely to be harbouring more of these types of fossils, it’s the Messel Pit, which in the past has served up the now notorious Darwinius masillae fossil, a fossilised beetle with its turquoise iridescence largely intact, and two turtles caught in the middle of doing, erm, turtle things…

The best-preserved fossils in the world from the Eocene epoch, which ran from around 56 to 34 million years ago, have been found here, and Smith and his team are already planning another trip back.

“This fossil is amazing,” says one of the researchers, Agustín Scanferla. “We were lucky men to study this kind of specimen.”

The find has been published in Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments.