2,000-year-old Roman Military Sandal with Nails Found in Germany

Archaeologists have discovered the remains of a 2,000-year-old Roman Military Sandal near an auxiliary Roman camp in Germany.

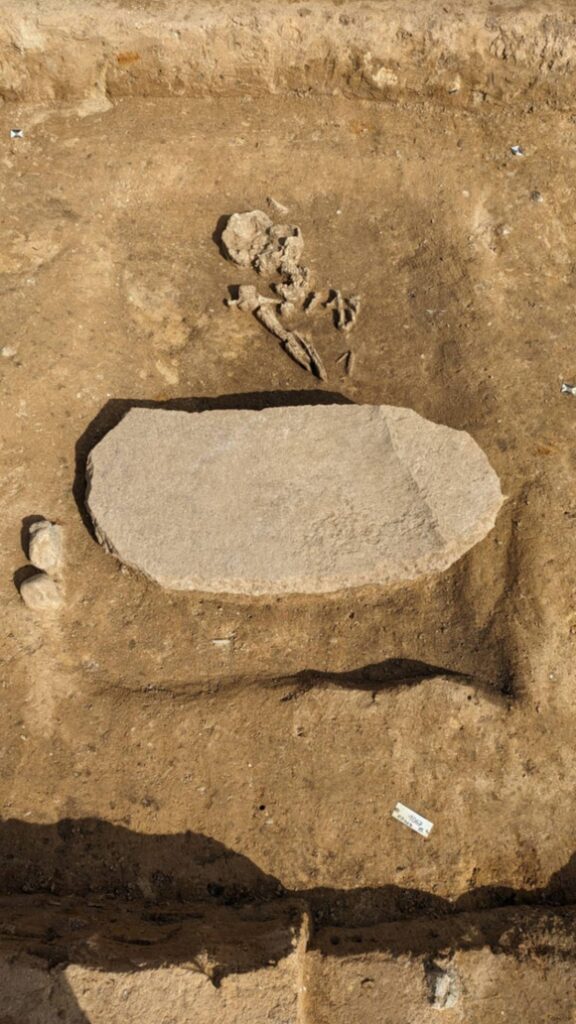

Archaeologists from the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation unearthed the military-style footwear while excavating at a civilian settlement on the outskirts of a Roman military fort near Oberstimm.

The settlement would have been occupied sometime between A.D. 60 and 130, according to a translated statement from the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (BLfD).

Surprising discoveries like the Oberstimm Sole show again and again that even after archaeological excavations are completed, valuable information is gathered.

This underscores the invaluable work of our restorers, says Mathias Pfeil, general conservator of the Bavarian State Office for the Conservation of Monuments (BLfD).

The rare find was disguised by a thick layer of corrosion, giving it the appearance of two indeterminate lumps of bent metal. Even, a curved and heavily corroded metal piece was initially suspected to be the remains of a sickle.

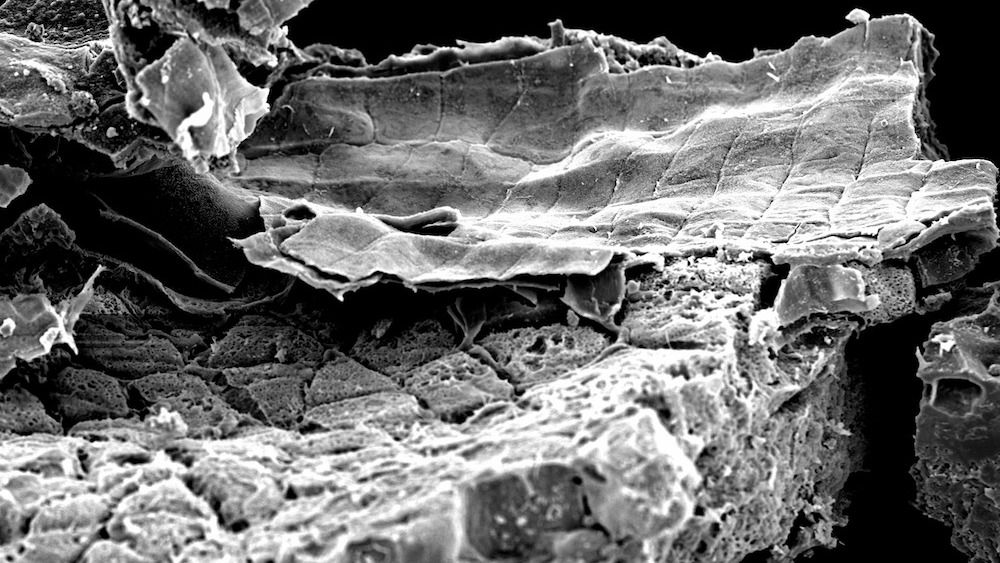

An X-ray at the laboratory of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (BLfD) revealed that the corroded lumps were hobnails.

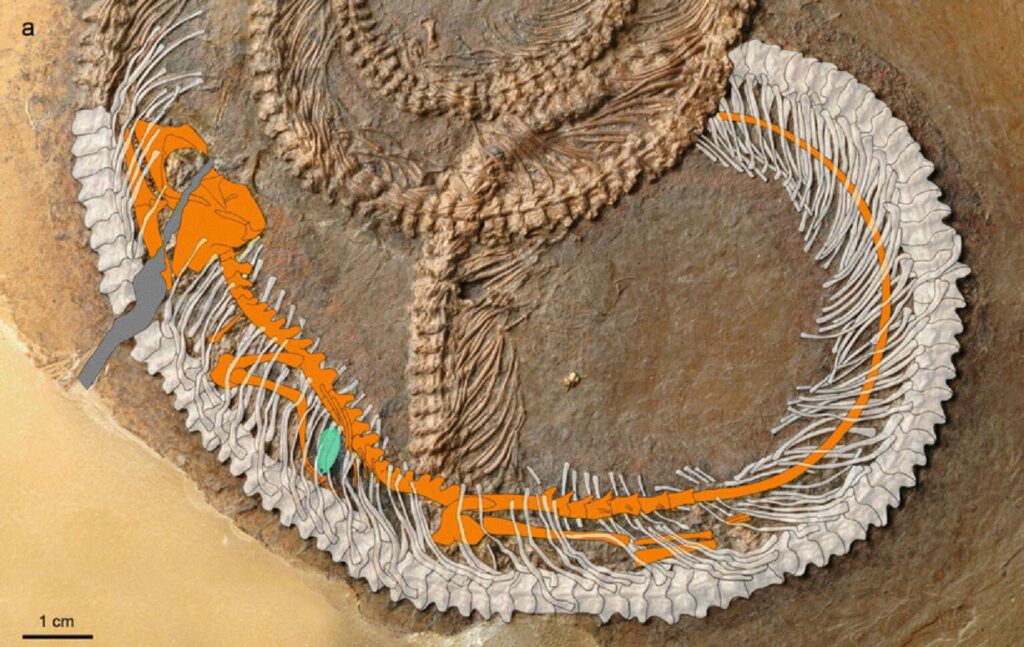

The shoe was a caliga, a heavy-duty, hobnailed sandal that was part of the uniform issued to Roman legionary soldiers and auxiliaries. The shoe would have been worn while the person was marching, with the nails providing traction.

The iron nails were used to reinforce and fix the leather sole. They provided stability and traction to the shoe when walking on difficult terrain, just like modern cleats do.

The discovery shows that the practices, lifestyles, and also the clothing that the Romans brought to Bavaria were adopted by the local people, says Amira Adaileh, a specialist at the Bavarian State Office for the Conservation of Monuments.

Individual shoe nails are frequently discovered at Roman sites, but only in certain circumstances are they preserved alongside remnants of the leather sole.

Comparable findings in Bavaria are known so far from only a handful of sites and they offer important new perspectives on Roman daily life and craftsmanship.