The Theopetra Cave and the Oldest Human Construction in the World

The Theopetra Cave is an archaeological site located in Meteora, in the central Greek region of Thessaly. As a result of archaeological excavations that have been conducted over the years, it has been revealed that the Theopetra Cave has been occupied by human beings as early as 130000 years ago.

In addition, evidence for human habitation in the Theopetra Cave can be traced without interruption from the Middle Palaeolithic to the end of the Neolithic period. This is significant, as it allows archaeologists to have a better understanding of the prehistoric period in Greece.

Occupation of Theopetra Cave

The Theopetra Cave is situated on the northeastern slope of a limestone hill, about 100 m (330 ft above a valley. The cave overlooks the small village of Theopetra, and the Lethaios River, a tributary of the Pineios River, flows nearby.

According to geologists, the limestone hill was formed between 137 and 65 million years ago, which corresponds to the Upper Cretaceous period.

Based on the archaeological evidence, human beings only began to occupy the cave during the Middle Palaeolithic period, i.e. around 130000 years ago.

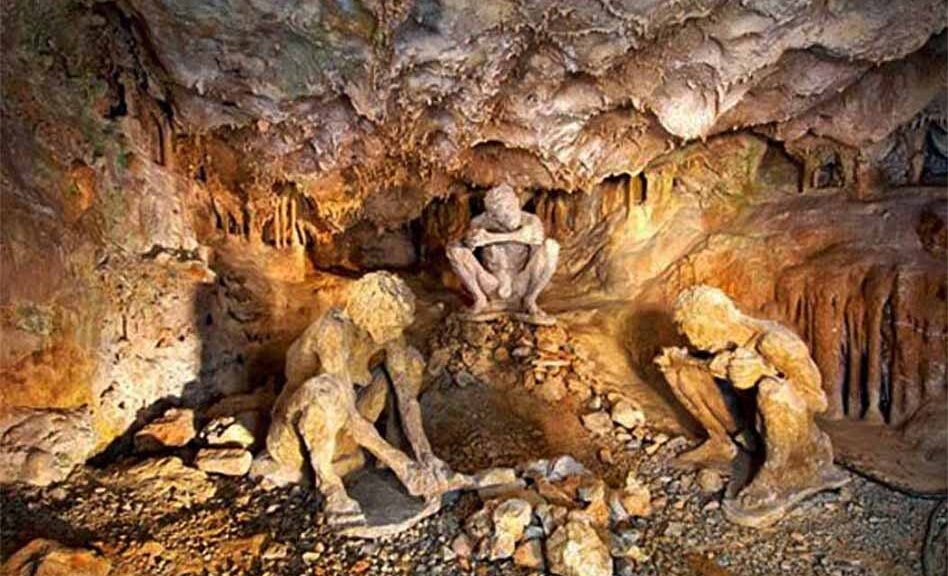

The cave itself has been described as being roughly quadrilateral in shape with small niches on its periphery and covers an area of about 500 sq meters (5380 sq ft). The Theopetra Cave has a large entrance, which allows light to enter abundantly into the interior of the cave.

Investigation Begins

The archaeological excavation of the Theopetra Cave began in 1987 and continued up until 2007.

This project was directed by Dr. Nina Kyparissi-Apostolika, who served as the head of the Ephorate of Palaeoanthropology and Speleography when the excavations were being carried out.

It may be mentioned that when the archaeological work was first conducted, the Theopetra Cave was being used by local shepherds as a temporary shelter in which they would keep their flocks. It may be added that the Theopetra Cave was the first cave in Thessaly to have been archaeologically excavated, and also the only one in Greece to have a continuous sequence of deposits from the Middle Palaeolithic to the end of the Neolithic period.

This is significant, as it has allowed archaeologists to gain a better understanding of the transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic way of life in mainland Greece.

Several interesting discoveries have been made through the archaeological study of the Theopetra Cave. One of these, for instance, pertains to the climate in the area when the cave was being occupied.

By conducting micromorphological analysis on the sediment samples collected from each archaeological layer, archaeologists were able to determine that there had been hot and cold spells during the cave’s occupation. As a result of these changes in the climate, the cave’s population also fluctuated accordingly.

The World’s Oldest Wall

Another fascinating find from the Theopetra Cave is the remains of a stone wall that once partially closed off the entrance of the cave.

These remains were discovered in 2010, and using a relatively new method of dating known as Optically Stimulated Luminescence, scientists were able to date this wall to be around 23000 years old.

The age of this wall, which coincides with the last glacial age, has led researchers to suggest that the wall had been built by the inhabitants of the cave to protect them from the cold outside. It has been claimed that this is the oldest known man-made structure in Greece, and possibly even in the world.

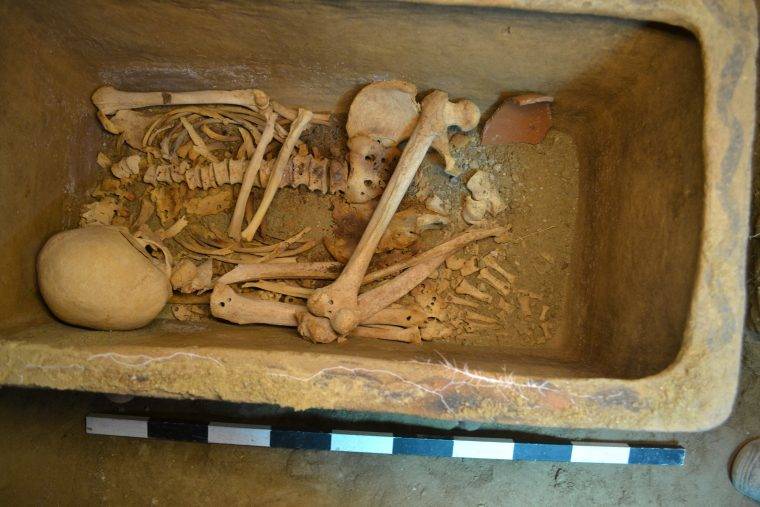

A year before this incredible discovery was made, it was announced that a trail of at least three hominid footprints that were imprinted onto the cave’s soft earthen floor had been uncovered. Based on the shape and size of the footprints, it has been speculated that they were made by several Neanderthal children, aged between two and four years old, who had lived in the cave during the Middle Palaeolithic period.

In 2009, the Theopetra Cave was officially opened to the public, though it was closed temporarily a year later, as the remains of the stone wall were discovered that year. Although the archaeological site was later re-opened, it was closed once again in 2016 and remains so due to safety reasons, i.e. the risk of landslides occurring.