Breathtaking Find Unearths 3,500-Year-Old Ancient Greek Tombs, Once Lined With Gold

Archaeologists recently discovered two magnificent 3,500-year-old royal tombs in the shadow of the palace of the legendary King Nestor of Pylos. It’s not clear exactly who the tombs’ owners were, but their contents—gold and bronze, amber from the Baltic, amethyst from Egypt, and carnelian from the Arabian Peninsula and India—suggest wealth, power, and far-flung trade connections in the Bronze Age world. And the images engraved on many of those artefacts may eventually help us better understand the Mycenaean culture that preceded classical Greece.

Tombs fit for royalty

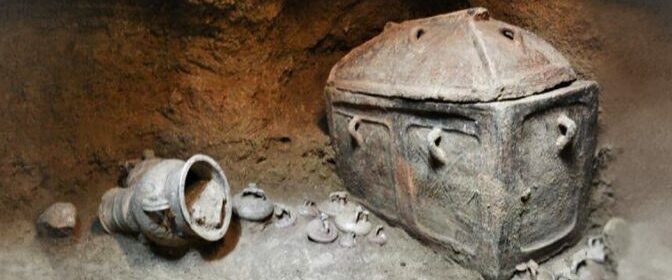

The larger tomb is 12m (36 feet) wide and 4.5 meters (15 feet) deep, and stone walls would once have stood that height again above ground.

Domes once covered the underground chambers, but the roofs and upper walls have long since collapsed, burying the tombs beneath thousands of melon-sized stones and a tangle of grapevines. University of Cincinnati archaeologists Jack Davis, Sharon Stocker, and their colleagues had to clear away vegetation and then remove the stones by hand.

“It was like going back to the Mycenaean period,” Stocker said. “They had placed them by hand in the walls of the tomb, and we were taking them out by hand. It was a lot of work.”

Beneath the rubble, gold leaf litters the burial pits’ floors in gleaming flakes; once, it lined the walls and floors of the chambers.

The tombs don’t appear to have contained the remains of their occupants (there’s some evidence that the tombs were disturbed in the distant past), but they were interred with jewellery and other opulent artefacts of gold, bronze, and gemstones, as well as a commanding view of the Mediterranean Sea.

For archaeologists, the real treasure in the Mycenaean tombs isn’t all the gold leaf or polished gemstones but the imagery engraved in those artefacts and what it can tell us about Mycenaean culture and beliefs.

Carved in stone

Today, we’ve got a pretty good grasp of classical Greek religion (and it’s still got a pretty good grip on popular culture). But classical Greece emerged from the ashes of the Mycenaean civilization, which crumbled like many other Mediterranean societies around 1200 BCE when the Bronze Age world suffered a sudden economic and political collapse.

Texts written in the earliest written form of Greek, a script called Linear B, describe the Bronze Age ideas that eventually gave rise to the more familiar classical Greek mythology.

Those texts mention some familiar names, like Zeus, Poseidon, and Athena, but those figures are not quite in the roles they hold in the later Greek pantheon. Zeus isn’t yet the ruler of the gods, while his brother Poseidon rules over earthquakes and the underworld. Other almost-familiar deities appear under different names.

But we don’t know what most of the symbols and motifs unearthed at Mycenaean archaeological sites mean or what role those symbols may have played in daily life, religious rituals, or other aspects of the culture.

“One problem is we don’t have any writing from the Minoan or Mycenaean time that talks of their religion or explain the importance of their symbols,” said Stocker.

A gold pendant suggests trade links with Egypt; it bears an image of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, whose domains include motherhood and the protection of the dead. Later Greek culture drew parallels between Hathor and the Greek goddess Aphrodite, but it’s not entirely clear what she meant to Mycenaeans.

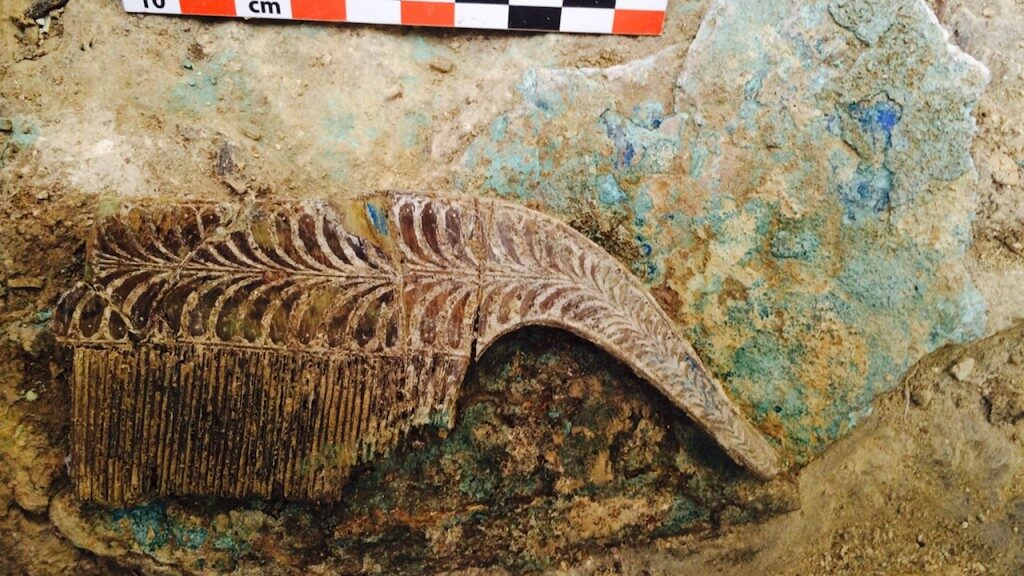

But one of the most interesting items from the tombs is an agate sealstone, a type of carved gemstone popular in the Minoan civilization that flourished on the island of Crete at around the same time as the Mycenaean civilization on the mainland.

Archaeologists think people may have carried sealstones as amulets. This one depicts two lion-like spirits, or genii, standing on their hind legs and carrying offerings—a serving vase and an incense burner—to an altar. The altar itself holds a sprouting sapling and a Minoan symbol that probably represents the horns of a sacrificial ox.

A 16-pointed star hangs over the whole scene. The elaborate star shape is a rare symbol on Mycenaean artefacts, but it shows up on two artefacts in the same tomb at Pylos: the agate sealstone and another gold and bronze item. Stocker, Davis, and their colleagues aren’t yet sure what the symbol means or why it may have been associated with the tomb’s occupant, but they’ll spend the next couple of years in the field and in the lab trying to better understand the tombs and their contents.

The Griffin Warrior

The pair of newly-discovered tombs lies close to another royal tomb, first excavated in 2015. It contained armour, weapons, gold jewellery, and another agate sealstone with a detailed combat scene engraved on it. Those warlike grave goods, combined with an ivory plaque bearing an engraving of a griffin, gave the tomb’s occupant the nickname “Griffin Warrior.”

Based on the style of the tomb and the nature of the things he took to the grave, Stocker, Davis, and their colleagues say the Griffin Warrior was probably a king who wielded both military and religious authority—a predecessor to later Mycenaean kings like Nestor, who features in the Greek epic poems The Iliad and The Odyssey. The two nearby tombs may hold relatives or family members of the Griffin Warrior, perhaps immediate family or members of the same dynasty.