Stone Inscribed With Ireland’s Ogham Script Found in England

A geography teacher was tidying his overgrown garden at his home in Coventry, England, when he stumbled across a rock with mysterious incisions. Intrigued, he sent photographs to a local archaeologist and was taken aback to learn that the markings were created more than 1,600 years ago and that the artefact was worthy of a museum.

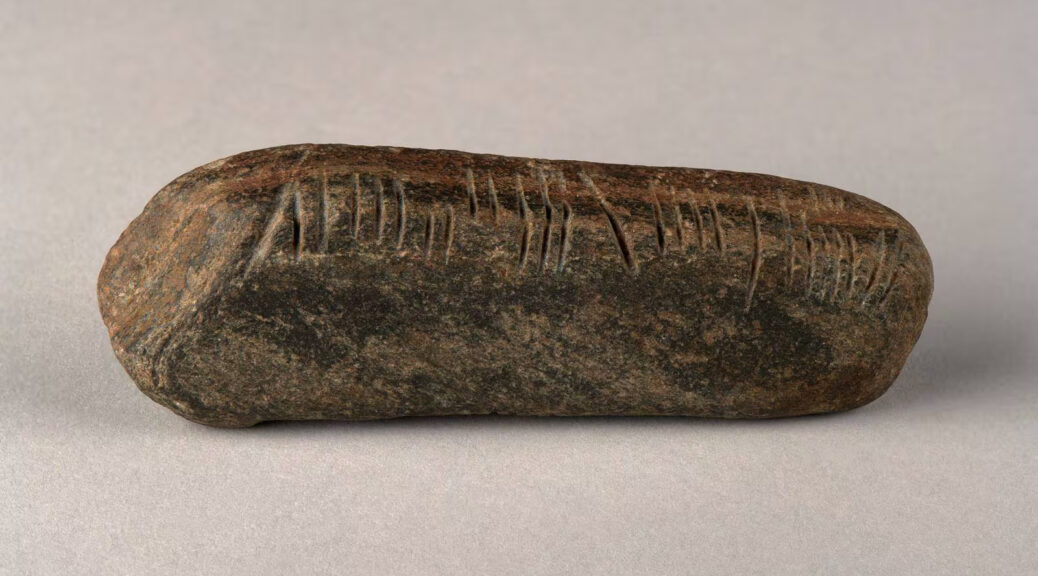

The rectangular sandstone rock that Graham Senior had discovered was inscribed in ogham, an alphabet used in the early medieval period primarily for writing in the Irish language.

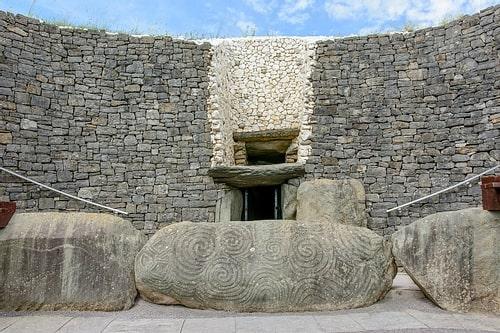

Before the people of Ireland began using manuscripts made from vellum, they used the ogham writing system, consisting of parallel lines in groups on materials such as stone. Rare examples of such stones offer an insight into the Irish language before the use of the Latin insular script.

Mr Senior (55) said: “I was just clearing a flower bed of weeds and stones when I saw this thing and thought, that’s not natural, that’s not scratchings of an animal. It can’t have been more than four or five inches below the surface.”

He washed it and consulted a relative who was an archaeologist, who suggested that he contact the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which encourages the recording of archaeological objects found by members of the public.

Teresa Gilmore, an archaeologist and finds liaison officer for Staffordshire and West Midlands based at Birmingham Museums, said: “This is an amazing find. The beauty of the Portable Antiquities Scheme is that people are finding stuff that keeps rewriting our history.

“This particular find has given us a new insight into early medieval activity in Coventry, which we still need to make sense of. Each find like this helps in filling in our jigsaw puzzle and gives us a bit more information.”

When Mr Senior sent her some photographs, she immediately saw its potential. She contacted Katherine Forsyth, professor of Celtic Studies at the University of Glasgow, who confirmed that it was an ogham script, that of an early style, which most likely dates to the fifth to sixth century but possibly as early as the fourth century.

Ms Gilmore said such stones were “very rare and have generally been found in Ireland or Scotland … so to find them in the [English] midlands is actually unusual.”

She suggested it could be linked to people coming over from Ireland or to early medieval monasteries in the area. “You would have had monks and clerics moving between the different monasteries.”

The stone, which is 11cm long and weighs 139g, is inscribed on three of its four sides.

Its purpose is unclear, said Ms Gilmore, adding: “It could have been a portable commemorative item. We don’t know. It’s an amazing little thing.”

Explaining its inscription, “Maldumcail/S/Lass”, Gilmore said.

“The first part relates to a person’s name, Mael Dumcail. The second part is less certain. We’re not sure where the S/ Lass comes from. It is probably a location. So something like ‘had me made’.”

Senior said it was exciting to be told that the artefact was significant, adding: “We’re not far from the river Sowe. My thinking is that it must have been a major transport route.”

The rock will be displayed at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry, to which Mr Senior has donated it permanently. It will feature in the forthcoming Collecting Coventry exhibition, which opens on May 11th.

Ali Wells, a curator at the museum, said: “It is really quite incredible. The language originates from Ireland. So, to have found it within Coventry, has been an exciting mystery. Coventry has been dug up over the years, especially the city centre, so there’s not that many new finds. It was quite unexpected.” – Guardian