Final Years of Life In Pompeii Revealed Through An Inscription

Pompeii was a city that was buried in ash in A.D. 79 as Mount Vesuvius erupted, and many people that lived there died. But before that catastrophic event, Pompeii was a wealthy city, and it was filled with parties and struggles

According to an inscription recently discovered on the wall of a tomb found in Pompeii in 2017.

The inscription describes a massive coming-of-age party for a wealthy young man. who reaches the age of an adult citizen.

According to the inscription, he threw a massive party that included a banquet serving 6,840 people and a show in which 416 gladiators fought over several days.

The inscription also tells of harder times, including a famine that lasted four years and another gladiator show that ended in a public riot, Massimo Osanna, the director-general of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, wrote in a paper published in the 2018 issue of the Journal of Roman Archaeology, which is published once a year.

Osanna deciphered the inscription and discussed some of the findings the inscription reveals, including new information that may allow researchers to determine how many people inhabited Pompeii.

Coming-of-age party

The inscription says that, when the wealthy man was old enough to wear the “toga virilis” (a toga worn by an adult male citizen), he threw a massive banquet and gladiator shows.

The banquet was served “on 456 three-sided couches so that upon each couch 15 persons reclined,” the inscription reads, as translated by Osanna.

This information could help researchers determine how many people lived in Pompeii in the decades before it was destroyed, Osanna wrote.

The inscription claims that 6,840 people attended the banquet. Because a banquet like that would likely be served only to adult males with political rights, and those men probably made up about 27% to 30% of Pompeii’s population, Osanna estimates Pompeii’s total population to have been about 30,000 people.

The gladiator show held by the wealthy man was “of such grandiosity and magnificence as to be able to be compared with [that of] any of the most noble colonies founded by Rome, since 416 gladiators participated,” the inscription says.

A show of this size would have taken several days, if not a week, Osanna wrote, noting that if each gladiator fought one-on-one, there would have been 213 separate fights.

Famine and riots

The inscription also mentions a famine, during which the wealthy man helped his fellow Pompeii citizens by selling wheat at discounted prices and organizing the distribution of free loaves of bread.

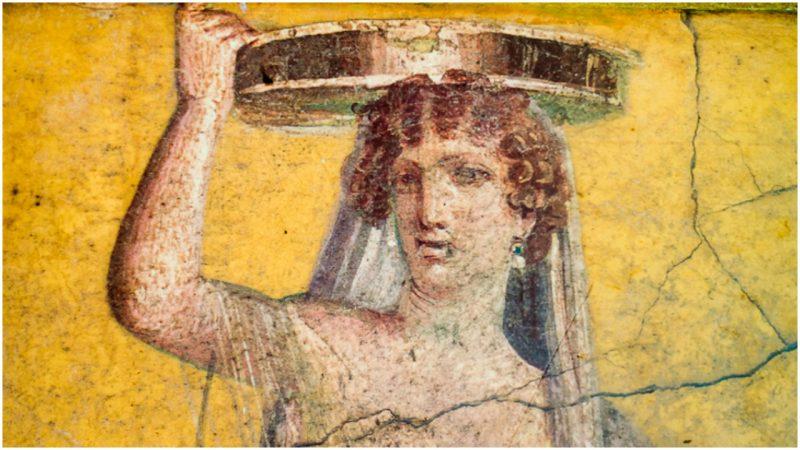

A famous mosaic from Pompeii shows three people, including a child, at a stall waiting to get bread, Osanna said, and it’s possible that the mosaic shows the event mentioned in the inscription.

Just 20 years before the Vesuvius eruption, in A.D. 59, a riot broke out during a gladiator show, according to the inscription.

The ancient Roman historian Tacitus (AD 56-120) also mentioned this riot in his book “Annals.” The inscription says that, as a penalty for the riot, Emperor Nero “ordered that they [Roman authorities] deport from the City beyond the two-hundredth mile all the gladiatorial households [schools].”Nero also ordered several Pompeii citizens involved in the riot to leave the city, according to the inscription.

The inscription claims that the wealthy man talked to Nero and convinced the emperor to allow some of the deported citizens to return to Pompeii — an indication of the high regard Nero seems to have held for the man, Osanna wrote.

Who was the wealthy man?

Osanna believes the wealthy man’s name and position were carved into a part of the tomb, which is now destroyed; it was looted in the 19th century.

The identity of the wealthy man could be Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, a man mentioned in other inscriptions from Pompeii, Osanna wrote. Maius is described as a man of great wealth and power who lived around A.D. 59, Osanna wrote. Previous archaeological work shows that a tomb belonging to Maius’ adoptive father, “Marcus Alleius Minius, is located near the tomb with the inscription.

The translation of the inscription is preliminary, and further studies may provide more information about it, Osanna wrote.