This Wooden Phallus Might Be a Rare 2,000-Year-Old Dildo

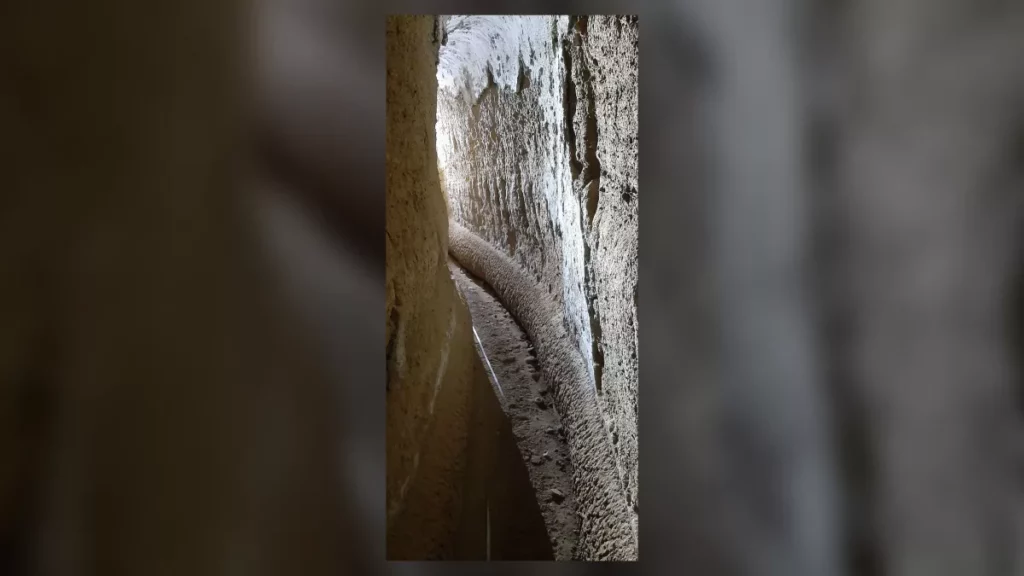

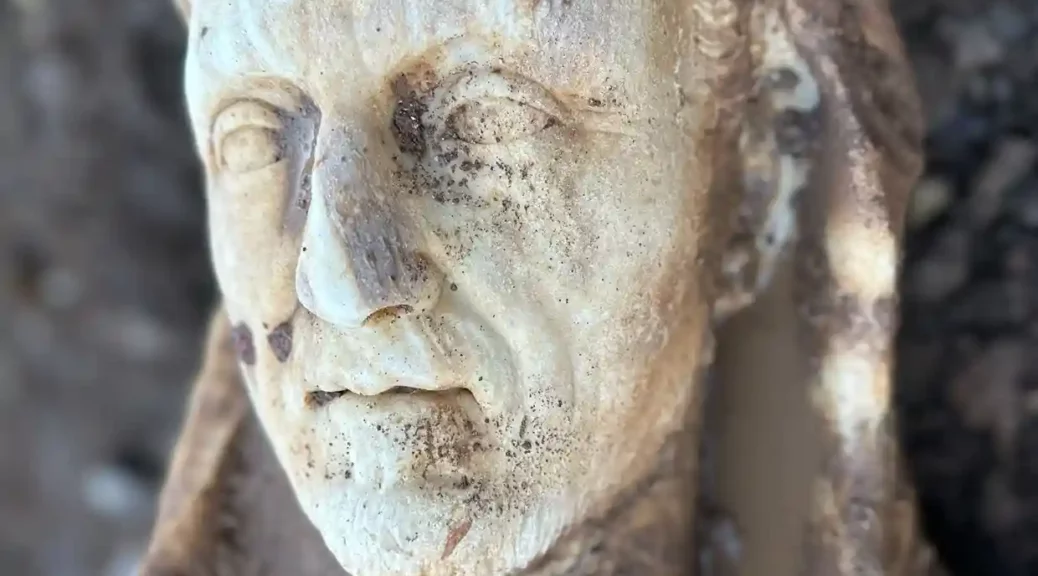

Archaeologists have uncovered what could be a rare example of an ancient sex toy carved from wood, found in a Roman fort known for a plethora of phallic motifs. The ruins of Vindolanda fort sit near Hadrian’s Wall in England on the borderlands of what was once the great Roman Empire.

On this politically tense frontier, where Roman soldiers faced off with ‘barbarians’ to the north, symbols representing penises were a ubiquitous sign of protection. Imagery of male genitalia can be found on just about anything, it seems; stone walls, the lids of boxes, even horse riding gear.

Yet the wooden phallus mentioned above is unlike any other penis unearthed at the site. Or at any other Roman dig for that matter. The object was initially discovered in 1992 and rather innocently assumed to be a darning tool. But researchers are now pretty sure that it is actually a disembodied penis.

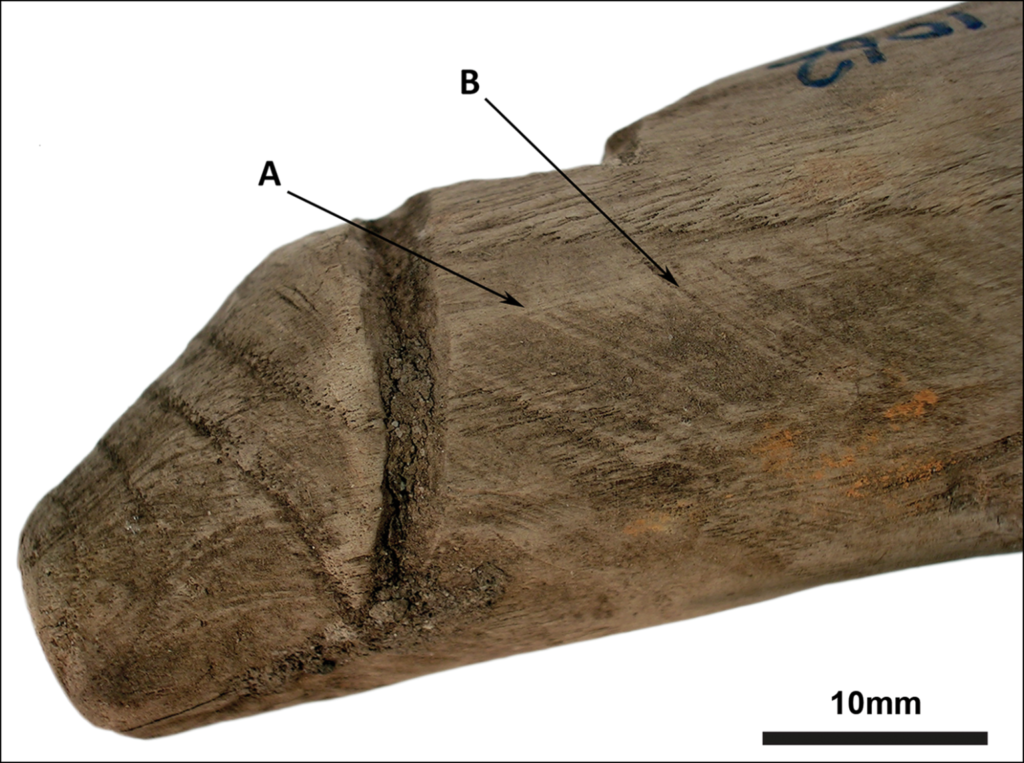

Apart from a carved line at the tip that looks suspiciously like the appendage’s glans, the wooden object is quite smooth, which suggests it made routine, rubbing contact with another surface.

Archaeologists have put forward three possible explanations for what that surface might have been. The 160-millimeter (6.3 inch) long implement could have been used as a grinding pestle, specially designed to ‘infuse’ food, cosmetics, or medicine with spiritual properties.

While the tool does look like it could crush soft materials, an absence of staining or discoloration on the object’s blunt end means there’s no easy way to confirm this particular hypothesis.

It’s also possible the wooden object was in fact a penis, one adorning a statue, or put on display outside of a building; a common feature in ancient Greece and Rome. People walking by might then have rubbed the penis for good luck. With no signs of outdoor weathering or of being removed or reinserted into an abrasive notch, this is also an unlikely purpose.

The third and final explanation put forward by researchers is the most interesting to consider: the ancient penis could be a uniquely preserved dildo from the second century CE.

“We know that the ancient Romans and Greeks used sexual implements – this object from Vindolanda could be an example of one,” says archaeologist Rob Collins from Newcastle University in England.

Today, we might be tempted to call it a sex toy, but archaeologists working on the artifact think that that term may not have applied in Roman times.

“Use may not have been exclusively sexual or for the pleasure of the user,” they explain.

“Such implements may have been used in acts that perpetuated power imbalances, such as between an enslaved person and his or her owner, as attested in the recurrence of sexual violence in Roman literature.”

The ancient dildo may not have even been used for penetration. In fact, the signs of wear on the object’s exterior might support clitoral stimulation better.

Researchers say the artifact shows “perceptibly greater wear at either end compared to its middle”.

This seems to align with signs of wear on a 2,000-year-old bronze dildo found in China, although experts say it’s hard to compare the patterns between such old artifacts.

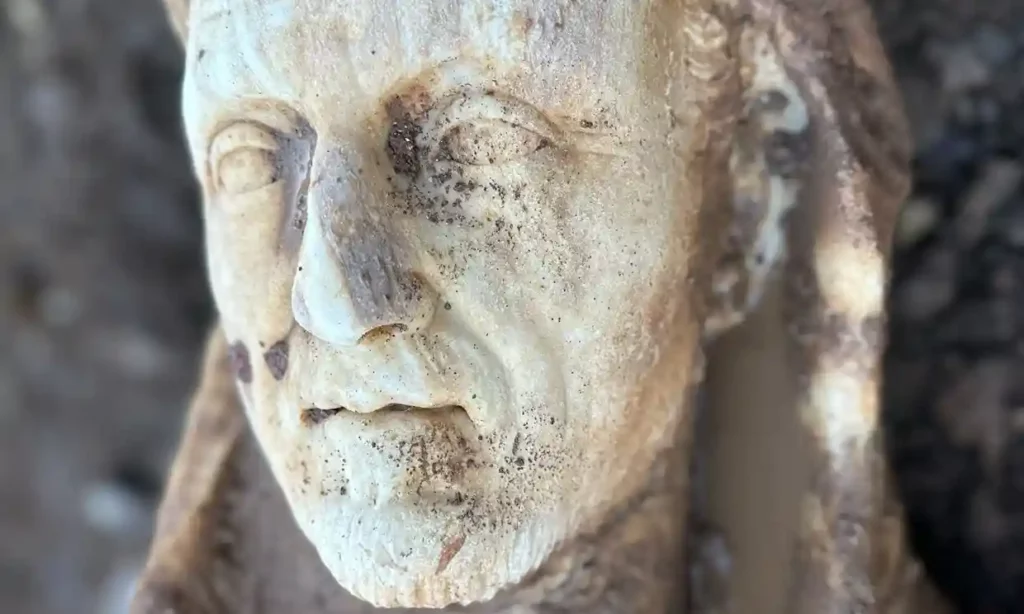

Although the wooden phallus from ancient Rome is “simple in form”, researchers suspect it was created by the hand of a confident artist, a practiced practitioner of penises, if you will.

In a Roman fort like Vindolanda, that would have been quite the skill.

“The Vindolanda phallus is an extremely rare survival,” says archaeologist Rob Sands from University College Dublin.

“It survived for nearly 2000 years to be recovered by the Vindolanda Trust… “

Interpreting the wooden phallus as a pestle or a good luck charm might be less problematic and uncomfortable explanations, but archaeologists argue we need to “accept the presence of dildos and the manifestation of sexual practices in the material culture of the past.”

The oldest suspected dildo ever found in archaeology dates back 28,000 years.

In all likelihood, these sexual instruments are a part of human history, whether we acknowledge them or not.