Ancient Snail From 99 Million Years Ago Discovered With Hairs Growing on Shell

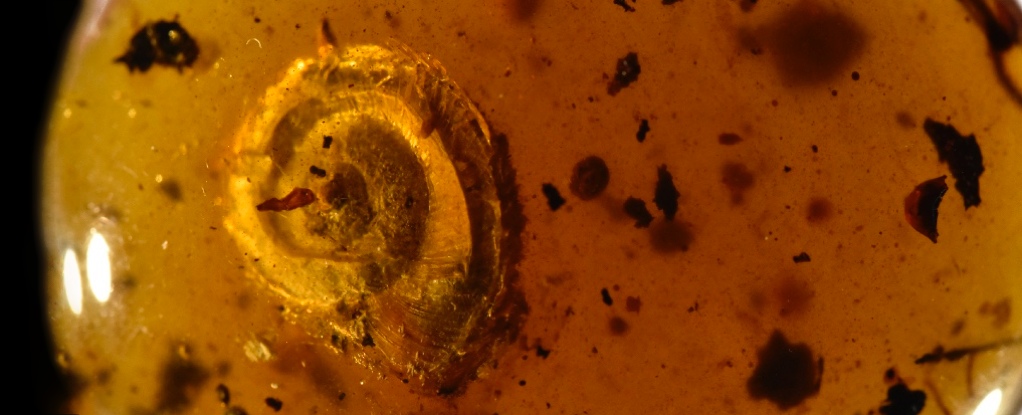

A snail preserved in amber with an intact fringe of tiny delicate bristles along its shell is helping biologists better understand why one of the world’s slimiest animals might evolve such a groovin’ hairstyle.

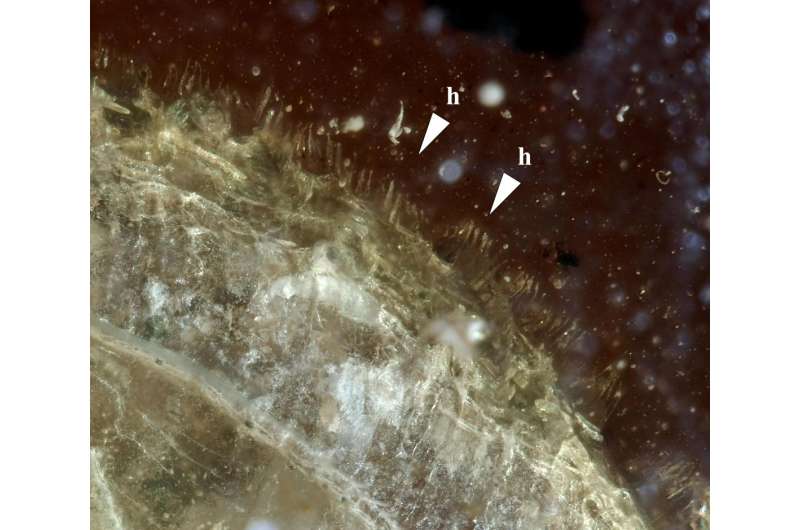

This unusual mollusc fossil, found in the Hukawng Valley of Myanmar, has lines of stiff, miniscule hairs, each between 150 and 200 micrometres long, following the swirl of its 9-millimetre long, 3.1-millimetre high shell.

It’s not the first hairy snail discovered, either, joining an exclusive club of coifed gastropods.

“This is already the sixth species of hairy-shelled Cyclophoridae – a group of tropical land snails – found so far, embedded in Mesozoic amber, about 99 million years old,” explains University of Bern palaeontologist Adrienne Jochum.

They’re not just some weirdo extinct critters, either. Several land snails still living today also have fuzzy shells.

A team of researchers led by malacologist Jean-Michel Bichain from the Museum of Natural History and Ethnography in France named the newly discovered animal Archaeocyclotus brevivillosus – its species name combining the Latin words small (brevis) and shaggy (villōsus).

Out of eight species found in Myanmar amber, six have hairy shells, suggesting this may be the ancestral state of these land snails. In fact, this fuzz may have helped snails transition from a watery environment to life on land during the Mesozoic period 252 to 66 million years ago, the researchers suggest.

The hairs are formed from the outermost protein-filled layer of the snail’s shell – the shell’s skin – called the periostracum. Adding hairs to a shell would cost the tiny animals energy, so it must have given these minuscule prehistoric snails some sort of selective advantage in their tropical environment to make it worthwhile.

Bichain and team speculate that these could have included water retention and protection against shell desiccation, allowing these animals to branch out into dryer soil niches. And just like our own mammalian hair, it’s possible the shell fuzz may have helped with thermoregulation.

“The bristles could also have served as camouflage or protected the snail against a direct attack by stalking birds or soil predators,” explains Jochum. “They may also have played a role in thermal regulation for the snail by allowing tiny water droplets to adhere to the shell, thereby serving as an ‘air conditioner’. And finally, it cannot be ruled out that the hairs provided an advantage in sexual selection.”

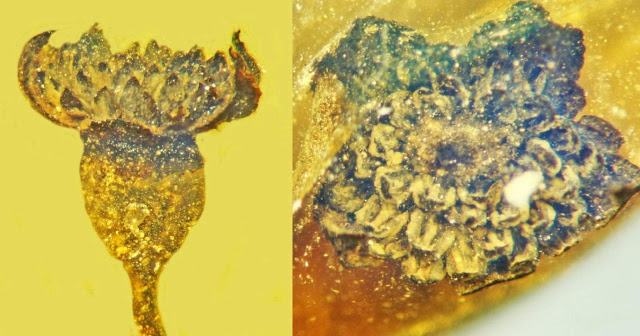

As well as shaggy snails, Myanmar amber has conserved over two thousand unique species from delicate flowers to an exquisitely preserved feathered dinosaur tail, providing a stunning window into the biodiversity of the Cretaceous period.

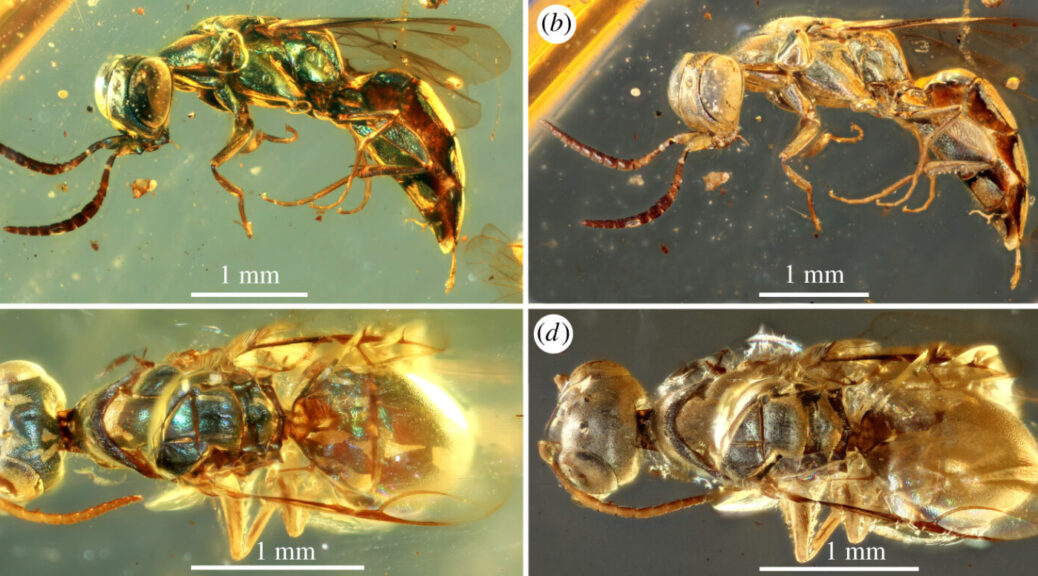

Signs of ancient species from the tropics are hard to come by, given the warm, moist conditions are ideal for the disintegration and recycling of organic matter. So animals preserved in amber fill in some of these gaps in our fossil records, providing details on soft tissues and even the metallic colours of ancient insects, which would otherwise be lost to time.

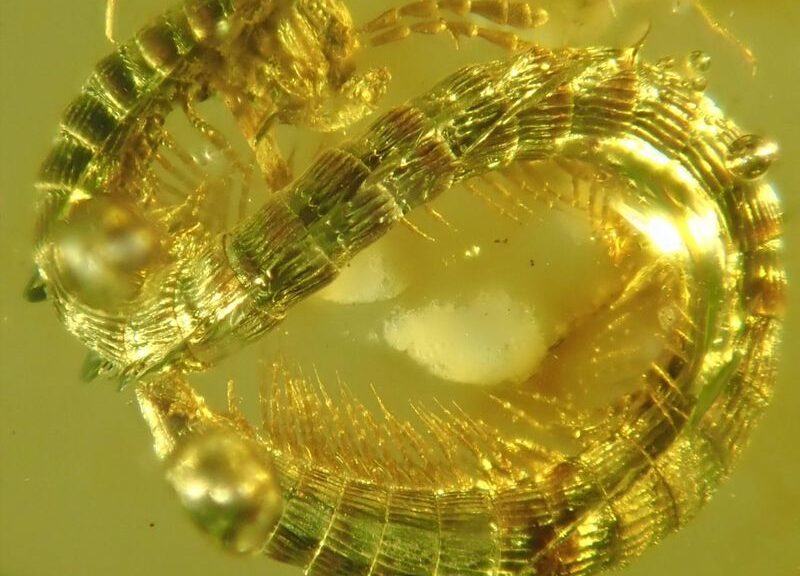

One such specimen preserved what may be the first evidence of live births in land snails (rather than egg laying), with neonate snails still attached to their mother through mucus.

Sadly, while the amber does hold many precious exquisite specimens, trade in the fossils is currently funding devastating conflicts in Myanmar. In recognition of this awful problem, the researchers note the amber-encased snail specimen was collected legally in 2017 before the current conflicts resumed.

Their study was published in Cretaceous Research.