Amber fossils reveal the true colours of 99-million-year-old insects

Nature is full of colours, from the radiant shine of a peacock’s feathers or the bright warning colouration of toxic frogs to the pearl-white camouflage of polar bears.

Usually, fine structural detail necessary for the conservation of colour is rarely preserved in the fossil record, making most reconstructions of the fossil-based on artists’ imagination.

A research team from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS) has now unlocked the secrets of true colouration in the 99-million-year-old insects.

Colours offer many clues about the behaviour and ecology of animals. They function to keep organisms safe from predators, at the right temperature, or attractive to potential mates. Understanding the colouration of long-extinct animals can help us shed light on ecosystems in the deep geological past.

The study, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B on July 1, offers a new perspective on the often overlooked, but by no means dull, lives of insects that co-existed alongside dinosaurs in Cretaceous rainforests.

Researchers gathered a treasure trove of 35 amber pieces with exquisitely preserved insects from an amber mine in northern Myanmar.

“The amber is mid-Cretaceous, approximately 99 million years old, dating back to the golden age of dinosaurs. It is essentially resin produced by ancient coniferous trees that grew in a tropical rainforest environment.

Animals and plants trapped in the thick resin got preserved, some with life-like fidelity,” said Dr. CAI Chenyang, associate professor at NIGPAS who lead the study.

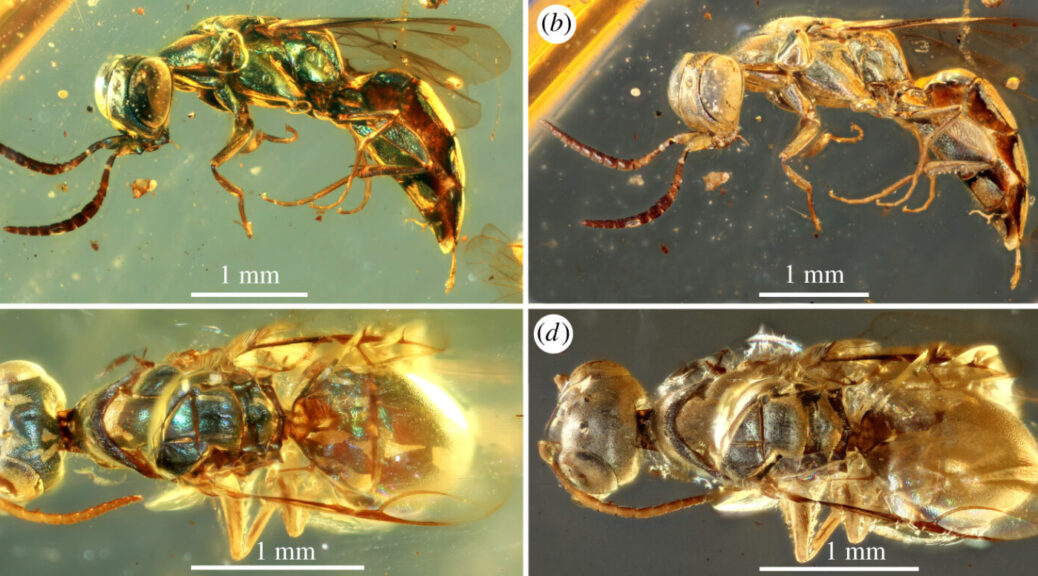

The rare set of amber fossils includes cuckoo wasps with metallic bluish-green, yellowish-green, purplish-blue or green colours on the head, thorax, abdomen, and legs. In terms of colour, they are almost the same as cuckoo wasps that live today, said Dr. CAI.

The researchers also discovered blue and purple beetle specimens and a metallic dark-green soldier fly. “We have seen thousands of amber fossils but the preservation of colour in these specimens is extraordinary,” said Prof. HUANG Diying from NIGPAS, a co-author of the study.

“The type of colour preserved in the amber fossils is called structural colour. It is caused by the microscopic structure of the animal’s surface. The surface nanostructure scatters light of specific wavelengths and produces very intense colours.

This mechanism is responsible for many of the colours we know from our everyday lives,” explained Prof. PAN Yanhong from NIGPAS, a specialist on palaeoecology reconstruction.

To understand how and why colour is preserved in some amber fossils but not in others, and whether the colours seen in fossils are the same as the ones insects paraded more than 99 million years ago, the researchers used a diamond knife blades to cut through the exoskeleton of two of the colourful amber wasps and a sample of the normal dull cuticle.

Using electron microscopy, they were able to show that colourful amber fossils have a well-preserved exoskeleton nanostructure that scatters light.

The unaltered nanostructure of coloured insects suggested that the colours preserved in amber may be the same as the ones displayed by them in the Cretaceous. But in fossils that do not preserve colour, the cuticular structures are badly damaged, explaining their brown-black appearance.

What kind of information can we learn about the lives of ancient insects from their colour? Extant cuckoo wasps are, as their name suggests, parasites that lay their eggs into the nests of unrelated bees and wasps.

Structural colouration has been shown to serve as camouflage in insects, and so it is probable that the colour of Cretaceous cuckoo wasps represented an adaptation to avoid detection.

“At the moment we also cannot rule out the possibility that the colours played other roles besides camouflage, such as thermoregulation,” adds Dr CAI.