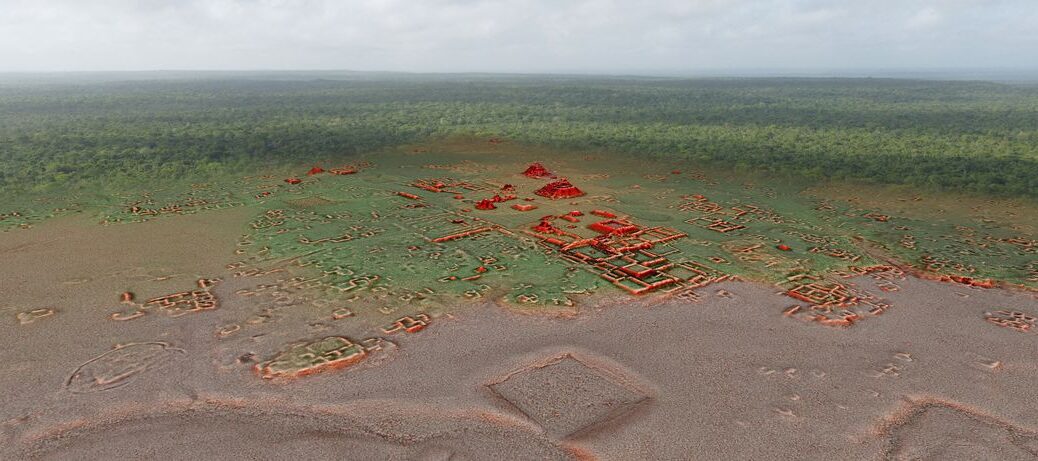

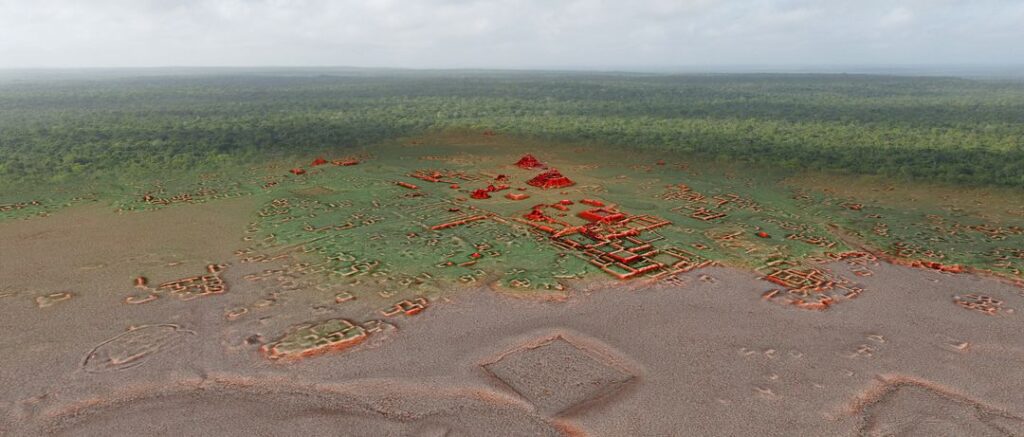

Lidar Survey Reveals Urban Sprawl of Ancient Maya City

Following years of research, Dr. Kathryn Reese-Taylor, PhD, professor in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at UCalgary, as well as her team of international colleagues, has used lidar (light detection and ranging) to help uncover more secrets of the enormous ancient Maya city of Calakmul.

As a result, researchers on the Bajo Laberinto Archaeological Project, a University of Calgary-led international and multidisciplinary research project directed by Reese-Taylor, can now better understand the density and landscape modifications of Mexico’s ancient Maya Calakmul settlement.

“By using lidar imagery, we are now able to fully understand the immense size of the Calakmul urban settlement and its substantial landscape modifications, which supported an intensive agricultural system,” says Reese-Taylor.

“All available land was covered with water canals, terraces, walls and dams, no doubt to provide food and water security for Calakmul residents.”

Although the number of people who lived at Calakmul during the height of the Snake King’s rule was not a complete surprise because of previous mapping and archaeological investigations by the Autonomous University of Campeche and INAH, the team was astonished at the scale and degree of urban construction.

Immense apartment-style residential compounds have been identified throughout the surveyed area, some with as many as 60 individual structures, the seats of large households composed of extended families and affiliated members.

These large residential units were clustered around numerous temples, shrines, and possible marketplaces, making Calakmul one of the largest cities in the Americas in 700 AD.

But that’s not all the team was able to see.

“We were also able to see that the magnitude of landscape modification equalled the scale of the urban population,” explains Reese-Taylor. “All available land was covered with water canals, terraces, walls, and dams, no doubt to provide maximum food and water security for the city dwellers.”

What’s next for the team and the technology

Going forward, the lidar survey will be used by INAH to help with policy and planning for the biosphere in anticipation of the expected increased tourism in the area.

The lidar will also continue to support the Bajo Laberinto Archaeological Project, which aims to investigate the causes of the rapid population increase at Calakmul and its effect on the region’s environment.

“We’re excited to see what else this technology will help us learn about Calakmul,” says Reese-Taylor. “It’s such a privilege to be unearthing the secrets of Mexico’s ancient settlements.”

Reese-Taylor and her colleagues on the Bajo Laberinto Archaeological Project will present their preliminary findings from the lidar survey on the INAH TV YouTube channel, on Tuesday, Oct. 25 at 5 p.m. MT.