Scientists In Kansas Discover 91-Million Year Old Fossil Of A Shark That Had Cannibal Babies

A newly discovered Cretodus Houghtonorum fossil shark aged 91 million years old in the Kansas region is part of the list of large dinosaur-era animals.

Cretodus houghtonorum was a spectacular, almost 7 feet long shark, or slightly more than 5 meters long, preserved in sediment deposited in an ancient ocean called the West’s Inland Waterway which covers North America during the Late Cretaceous period (144 million to66 million years ago), based on a study published in the Journal of Vertebrate paleontology.

In 2010, researchers Kenshu Shimada and Michael Everhart and 2 people of central Kansas, Fred Smith and Gail Pearson, found and excavated the fossil shark on the ranch near Tipton, Kansas.

Shimada is a professor of paleobiology at DePaul University in Chicago. He and Everhart are both adjunct research associates at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas.

The species name houghtonorum is in honor of Keith and Deborah Houghton, the landowners who donated the specimen to the museum for science. Although a largely disarticulated and incomplete skeleton, it represents the best Cretodus specimen discovered in North America, according to Shimada.

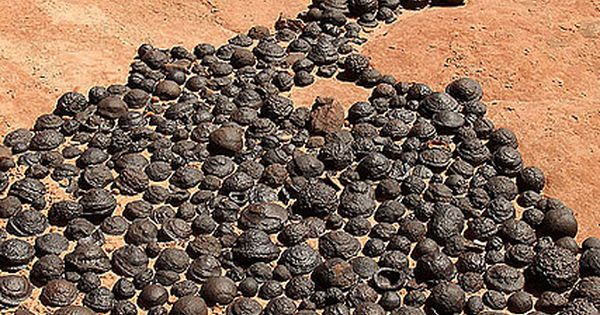

The discovery consists of 134 teeth, 61 vertebrae, 23 placoid scales and fragments of calcified cartilage, which when analyzed by scientists provided a vast amount of biological information about the extinct shark.

Besides its estimated large body size, anatomical data suggested that it was a rather sluggish shark, belonged to a shark group called Lamniformes that includes modern-day great white and sand tiger sharks as distant cousins, and had a rather distinct tooth pattern for a lamniform shark.

“Much of what we know about extinct sharks is based on isolated teeth, but an associated specimen representing a single shark individual like the one we describe provides a wealth of anatomical information that in turn offers better insights into its ecology,” said Shimada, the lead author on the study.

“As important ecological components in marine ecosystems, understanding about sharks in the past and present is critical to evaluate the roles they have played in their environments and biodiversity through time, and more importantly how they may affect the future marine ecosystem if they become extinct,” he said.

During the excavation, Shimada and Everhart believed they had a specimen of Cretodus crassidens, a species originally described from England and subsequently reported commonly from North America.

However, not even a single tooth matched the tooth shape of the original Cretodus crassidens specimen or any other known species of Cretodus, Shimada said.

“That’s when we realized that almost all the teeth from North America previously reported as Cretodus crassidens belong to a different species new to science,” he noted.

The growth model of the shark calibrated from observed vertebral growth rings indicates that the shark could have theoretically reached up to about 22 feet (about 6.8 meters).

“What is more exciting is its inferred large size at birth, almost 4 feet or 1.2 meters in length, suggesting that the cannibalistic behavior for nurturing embryos commonly observed within the uteri of modern female lamniforms must have already evolved by the late Cretaceous period,” Shimada added.

Furthermore, the Cretodus houghtonorum fossil intriguingly co-occurred with isolated teeth of another shark, Squalicorax, as well as with fragments of two fin spines of a yet another shark, a hybodont shark.

“Circumstantially, we think the shark possibly fed on the much smaller hybodont and was in turn scavenged by Squalicorax after its death,” said Everhart.

Discoveries like this would not be possible without the cooperation and generosity of local landowners, and the local knowledge and enthusiasm of amateur fossil collectors, according to the authors.

“We believe that continued cooperation between paleontologists and those who are most familiar with the land is essential to improving our understanding of the geologic history of Kansas and Earth as a whole,” said Everhart.

The new study, “A new large Late Cretaceous lamniform shark from North America with comments on the taxonomy, paleoecology, and evolution of the genus Cretodus,” will appear in the forthcoming issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.