The ancient giants of Nevada and the mystery of lovelock cave

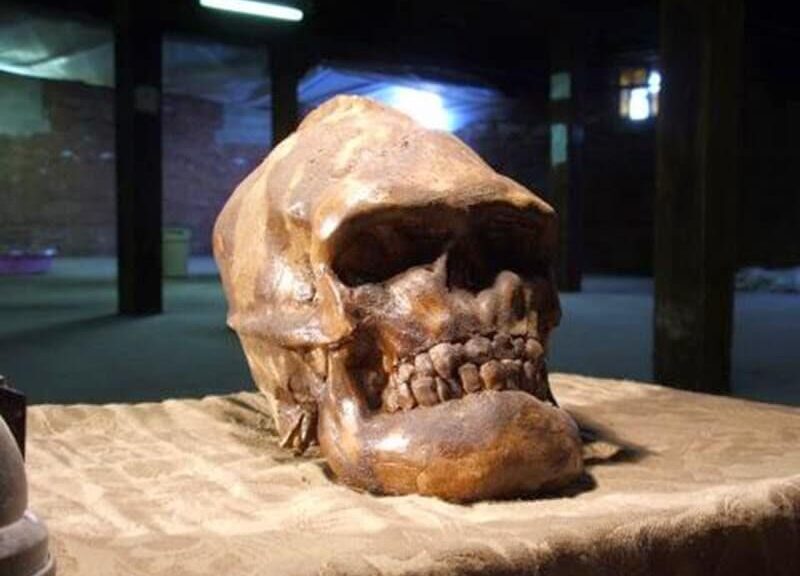

For more than a century, a story has persisted about the skeletons of giants being found in Lovelock Cave in northern Nevada. For many years, human remains were put on display in museums here and elsewhere, but that changed. Most of the bones and skulls that were once considered to be historical artifacts have been returned to tribes for burial.

If oversized bones from the so-called Lovelock giants ever existed, they are no longer available to the public. But their story behind the legend persists. Slicing through the bone-dry Humboldt sink on a long dirt road, it’s hard to imagine that all of it was once underwater.

Remnants of a vast ancient lake can still be seen in the distance. For generations of first Americans, this was a lush paradise of tules, fish, and waterfowl. Humans have climbed the same narrow path up the jagged mountain for more than 4,000 years. That’s how long indigenous peoples lived in and around the Lovelock Cave.

The roof of the cave is coated with soot from countless campfires lit by ancestors of the Paiutes. According to tribal lore, a race of red-headed giants made its last stand in the cave.

Reporter George Knapp: “Among today’s Paiutes, do most say the giants were real?”

Devoy Munk: “All that I’ve talked to say yes. I’ve haven’t heard anybody say no.”

Devoy Munk, a Lovelock historian, has spent all of her 80-plus years in Lovelock. Her family’s home today houses a small museum, jam-packed with artifacts and depictions documenting centuries of native culture and pioneer life.

Munk has earned the trust of Paiute elders who say the stories are true, and that the red-headed interlopers not only killed but ate their ancestors.

“My Indian friends tell me they were cannibals, that they set traps. They dug holes in pathways where they walked, covered them, and then Indians would fall in, and they said the best parts to eat were the thighs,” Munk said.

On Internet sites and alien-themed TV shows, the gruesome legend has blossomed, but it’s hardly new. Versions have been told and retold in magazines, even scholarly journals for more than a century.

Famed Nevadan Sarah Winnemucca first wrote in her acclaimed book that the Paiutes waged a three-year war against a tribe of red-headed cannibals before trapping — then killing — the last of them inside lovelock cave.

Her book doesn’t mention giants, and mainstream archeologists have vigorously rejected the entire story, to the point that the state museum in Winnemucca admonishes visitors at its front entrance that the red-headed giants are a myth.

“There have been skeletons pulled out of the Reid collection,” said Bill Snodgrass. “They found some in there roughly 6’2″. When you think about it, back then, six-foot was a very tall individual.”

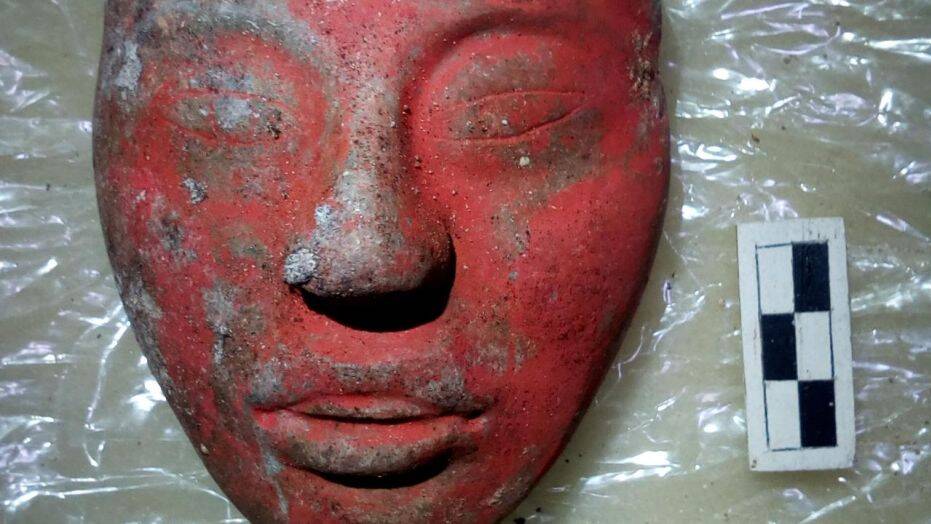

Snodgrass is the curator of the Marzen House Museum in Lovelock and thinks there is a reasonable basis for parts of the story. In the early 20th century, guano miners began excavating the Lovelock Cave and uncovered thousands of artifacts along with mummified remains including a few specimens much taller than the typical Paiute of centuries past.

Later scientific excavations found troves of native antiquities along with bones. Some human remains were destroyed. Others went to museums for display. A few, Snodgrass says, were consumed in bizarre initiation rituals. He adds there is evidence — including basketry — of an unknown culture that lived near the cave. Records show some of them had red hair.

“I can’t say who they were, redheads or not. Some say uric acid changes the color of hair, but there was definitely a different people here,” Snodgrass said.

Many, if not most, of the visitors who end up at the Marzen House Museum, have questions about the red-headed cannibals. The locals still enjoy the debate.

Reporter George Knapp: “The two of you disagree but it’s a friendly disagreement?”

“Oh yes. We’ve had this discussion and he hasn’t convinced me and I haven’t convinced him,” Munk said. Whether the red-headed giants ever existed, visits to the two museums are worth the drive.