An Ancient society is 2,500 years older than the Egyptian Pyramids

Ancient Egypt may appear as the epitome of an advanced early civilisation to many by its impressive pyramids and complex rules. However, recent research reveals the civilization of the Indus Valley in India and Pakistan, known for its well-planned settlements and outstanding art, before Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Experts now assume that it is 8,000 years old – 2,500 years older than commonly believed – and still considered one of the oldest cultures in the world. Their study also sheds new light on why the seemingly flourishing civilization collapsed.

A team of researchers from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Institute of Archaeology, Deccan College Pune, and IIT Kharagpur, have analyzed pottery fragments and animal bones from the Bhirrana in the north of the country using carbon-dating methods.

‘Based on radiocarbon ages from different trenches and levels the settlement at Bhirrana has been inferred to be the oldest (>9 ka BP) in the Indian sub-continent,’ the experts wrote in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal.

They used also used ‘optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) method’ to check the dating and investigate whether the climate changed when the civilization was thriving, to fill ‘a critical gap in information … [about] the Harappan [Indus Valley] civilization.’

While more tests are required, the study suggests the Indus Valley Civilisation pre-dates those of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, which are also famed for their impressive ability to build organized cities.

It’s thought the civilization spread across parts of what is now Pakistan and northwest India in the Bronze Age and at its peak, some five million people lived in one million square miles along citadels built near the basins of the Indus River.

Pottery and metals discovered at various ancient sites in the region indicate the people were skilled craftsmen and metallurgists, able to work copper, bronze, lead, and tin, as well as bake bricks and control the supply and drainage of water.

Anindya Sarkar, a professor at the department of geology and geophysics at IIT Kharagpur, told International Business Times: ‘Our study pushes back the antiquity to as old as 8th millennium before present and will have major implications to the evolution of human settlements in Indian sub-continent.’

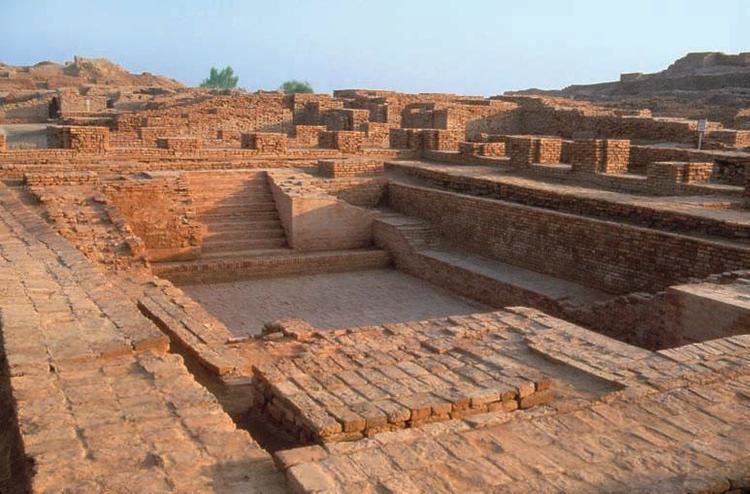

The archaeological sites at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan, show the ancient people were adept town planners and farmers.

Discovered in the 1920s, the Unesco site of Mohenjo-Daro is one of the largest and most advanced settlements of the Indus Valley Civilisation, with streets arranged round rectangular brick houses, two large assembly halls, a market place, public baths, and a central well.

Individual households got their water from smaller wells and wastewater was channelled into main streets, with some more lavish properties boasting their own bath and a second storey.

Experts have previously suggested the seemingly successful and advanced civilization was gradually wiped out when the Indus River dried up as the result of climate change. There are many other theories too, including an Aryan invasion, catastrophic floods, changing sea levels, societal violence, and the spread of infectious diseases.

But the team has come up with a new theory.

‘Our study suggests that the climate was probably not the cause of Harappan decline,’ they wrote.

While the ancient people relied upon heavy and regular monsoons between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago to water their crops, after this period, evidence at Bhirrana shows people continued to survive despite changing weather patterns.

‘Increasing evidence suggests that these people shifted their crop patterns from the large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species of small millets and rice in the later part of declining monsoon and thereby changed their subsistence strategy,’ they continued.

However, changing the crops they grew and harvested resulted in the ‘de-urbanization’ of cities and no need for large food storage facilities. Instead, the people swapped to personal storage spaces to look after their families.

‘Because these later crops generally have a much lower yield, the organized large storage system of mature Harappan period was abandoned giving rise to smaller more individual household-based crop processing and storage system and could act as a catalyst for the de-urbanization of the Harappan civilization rather than an abrupt collapse,’ the team wrote.