Archaeological Site in Peru Is Called Oldest City in the Americas

A complex of American pyramids that may be older than the pyramids of Egypt stands on a high, dry terrace overlooking a lush river valley in the Andes Mountains of Peru. These structures are remnants of the ancient city of Caral, which some have called the oldest society in the Americas.

According to groundbreaking research published in Science back in 2001, Caral was founded around 5,000 years ago. That origin date places it before the Egyptian pyramids in Africa and roughly 4,000 years before the Incan Empire rose to power on the South American continent. That history, and the sheer scope of the site, prompted UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural.

Caral sits in the Supe Valley, a region of Peru’s high desert nestled between the rainforest, mountains and the Pacific coast. The valley is brimming with ancient monumental architecture. And in the decades since Caral first made headlines, archaeologists working in the region have turned up about 18 nearby cities, some of which may be even older.

Taken together, these ancient people represent a complex culture now called Norte Chico. These people lived at a time when cities were on Earth, and perhaps non-existent elsewhere in the so-called New World. Even more incredible is that the civilization pre-dated the invention of ceramic pottery by some six centuries, yet they could master the technological prowess required to build monumental pyramids.

Much remains a mystery about this culture, but if archaeologists can unlock the secrets of Caral and its ancient neighbours, they may be able to understand the origins of Andean civilizations — and the emergence of the first American cities.

The Pyramids of Caral

A German archaeologist named Max Uhle first stumbled across Caral in 1905 during a wide-ranging study of ancient Peruvian cities and cemeteries. The site piqued his interest, but Uhle didn’t realize the large hills in front of him were actually pyramids. Archaeologists only made that discovery in the 1970s. And even then, it took another two decades before Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Shady kicked off systematic excavations of the region.

In 1993, working on weekends with the help of her students, Shady began a two-year survey of the Supe Valley that would ultimately yield a staggering 18 distinct settlements. No one knew how old they were, but the cities’ similarities and more primitive technologies implied a single, ancient culture that predated all others in the region.

By 1996, Shady’s work attracted a small fund from the National Geographic Society, which was enough to launch her Caral Archaeological Project working at the heart of the main city itself.

And when her team’s initial results were published in 2001, their study set the narrative for Caral as we still appreciate it today. The global press heralded it as the first city in the Americas. “Caral … was a thriving metropolis as Egypt’s great pyramids were being built,” Smithsonian Magazine reported. The BBC said the find offered hope to a century-long archaeological search for a “mother city” — a culture’s true first transition from tribal family units into urban life. Such a discovery could help explain why humanity made the leap.

Ruth’s work would make her an icon in Peruvian archaeology. As a 2006 feature in Discover put it, “She has dug [Caral’s] buildings out of the dust and pried cash from the grip of reluctant benefactors. She has endured poverty, political intrigue, and even gunfire (her bum knee is a souvenir of an apparent attempted carjacking near the dig site) in the pursuit of her mission.”

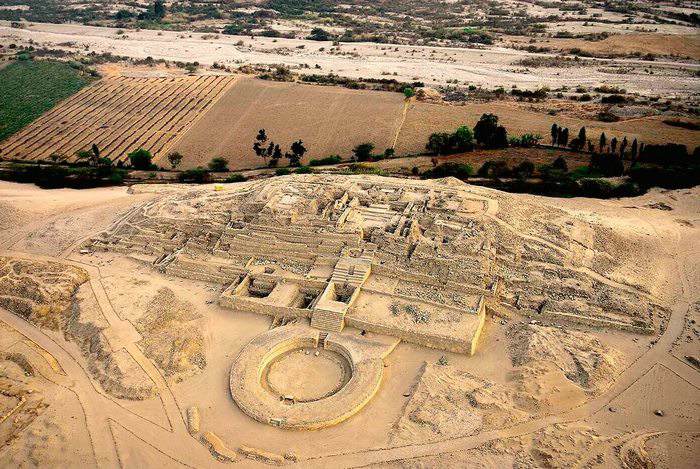

She continues to study the ancient society today, eking out new clues buried in the desert. Over decades, her long-running project has revealed that the “Sacred City of Caral-Supe” covers roughly 1,500 acres of surprisingly complex and well-preserved architecture. At its height, Caral was home to thousands of people and featured six pyramids, sunken circular courts, monumental stone architecture and large platform mounts made of earth. To researchers, these buildings are a testament to a forgotten ceremonial and religious system.

She now holds honorary doctorate degrees from five universities and a Medal of Honor from Peru’s congress. In November of 2020, the BBC named her to their 100 Women of 2020 list.

But controversy has also emerged in the two decades since the seminal study. Shady had a falling out with her co-authors in the years after their publication that turned nasty. Soon, other researchers had also started producing radiocarbon dates from the ancient cities that surround Caral. Surprisingly, some of those dates suggest they could be even older. Those dates could simply be evidence that these cities all existed simultaneously as part of a larger culture in this valley in the Andes. Or, it could be a sign that the true oldest city has yet to be found.

Influence on the Inca

Whichever city in the area is oldest, Norte Chico presents a puzzle for human history. Until recent years, conventional wisdom held that people first reached North America in earnest 13,000 years ago via a land bridge that appeared as the Ice Age thawed. A steady stream of sites older than that has since been found. In Peru, human remains have shown that hunter-gatherers lived in the region as far back as at least 12,000 years ago. And there are traces of settlements along the Pacific Coast from 7,000 years ago. The residents of Caral were likely the ancestors of these people who decided to settle down and build cities in the Supe Valley.

But why would the mother city of the Americas emerge so early in South America? Well-known sites in North America, like the cities of the Olmec, as well as Chaco Canyon and Moundville, weren’t built until thousands of years later.

To archaeologists, unlocking the story of Caral — and what became of the people who lived there — could carry implications for the story of the Americas as a whole. The Caral civilization survived for nearly a millennium, until, some researchers suspect, climate change wiped it out. But the people and their ideas didn’t disappear. Scientists see Caral’s influence in cultures that lived long after they were gone. All along the Peruvian coast, there are signs of mounds, circular structures and urban plans similar to those at Caral.

Archaeologists also found a khipu (or quipu) recording device at the site. For thousands of years after Caral’s demise, and throughout the Inca Empire, cultures in the Andes would use this system of knots as a kind of recorded language unlike any other known in the world.

The genetic heritage of the Caral people may also survive even today. A sweeping genetic study of modern Peru, published in Nature in 2013, showed that despite the Spanish influence, people in many regions of the nation can trace their genetic heritage all the way back to the first settlers of South America. It’s a line that runs right through Caral.