Ancient Footprints Offer Evidence Humans Wore Shoes 148,000 Years Ago

A new analysis of ancient footprints in South Africa suggests that the humans who made these tracks might have been wearing hard-soled sandals.

Ichnological evidence from three palaeosurfaces on the Cape Coast, in conjunction with a neoichnological study, suggests that humans may indeed have worn footwear while traversing dune surfaces during the Middle Stone Age.

The study is published in the journal Ichnos.

While researchers are reluctant to shoehorn in any firm conclusions regarding the use of footwear in the distant past, the prints’ unusual characteristics may provide the oldest evidence yet that people used shoes to protect their feet from sharp rocks in the Middle Stone Age.

No direct dates have been assigned to the well-preserved markings found on stone slabs at three different sites along the Cape Coast, according to the study’s authors.

However, the researchers hypothesize that tracks discovered at a location known as Kleinkrantz may be between 79,000 and 148,000 years old based on the age of other nearby rocks and sediments.

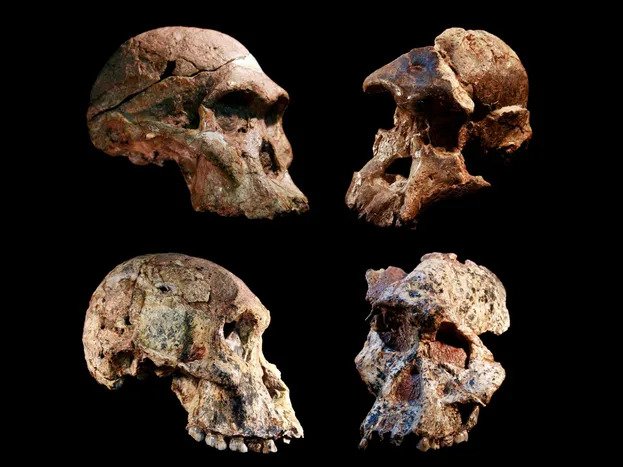

The footprints show no toes, discerning it from barefoot markings, and instead displayed “rounded anterior ends, crisp margins, and possible evidence of strap attachment points.’ Similar markings that are estimated to have been left between 73,000 and 136,000 years ago were located at a site called Goukamma.

The study authors wrote: “In all cases the purported tracks have dimensions that are broadly consistent with those of hominin tracks.” They added that the “track sizes appear to correspond to the tracks either of juvenile track-makers, or else small-adult hominin track-makers.”

To test this conclusion, the researchers made their own footprints wearing sandals resembling two different pairs of shoes used historically by the Indigenous San people of southern Africa, both of which are currently housed in museums.

Experiments revealed that the use of hard-soled footwear on wet sand left prints with crisp edges, no toe prints, and indentations where the leather straps met the sole – just like the markings at Kleinkrantz.

“While we do not consider the evidence conclusive, we interpret the three sites […] as suggesting the presence of shod-hominin trackmakers using hard-soled sandals,” write the researchers. Offering a possible motive for the use of such footwear, they go on to explain that coastal foraging involves clambering over sharp rocks while also posing the risk of stepping on sea urchins.

“In the [Middle Stone Age], a significant foot laceration might have been a death sentence,” they say. In this scenario, sandals would have been a lifesaver.

Despite their promising findings, researchers are reluctant to make any bold claims. This is due to a variety of factors, such as the difficulty of interpreting rock markings, as well as the fact no actual shoes from the Middle Stone Age have ever been found.

As such, they refrain from making major claims about their findings, but speculate that “humans may have indeed worn footwear while traversing dune surfaces during the Middle Stone Age.”

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2023.2249585