1,600-year-old Hunnic double burial found in Poland

In 2018, archaeologists uncovered a 1,600-year-old double burial in the village of Czulice near Krakow, Poland, containing the remains of two young boys.

This discovery, reported in the June issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, provides some of the earliest evidence of Hunnic presence in Europe. Radiocarbon dating placed the burial between CE 395 and 418, making it the oldest known Hunnic burial site in Poland.

As warriors, the Huns inspired almost unparalleled fear throughout Europe. Attila was the last sole king of the Huns. He ruled a vast empire, that from its firm center in Pannonia extended to the Baltic Sea and the “islands of the Ocean” in the north, and to the Caspian Sea in the east. Attila’s military prowess was so formidable that both the Eastern (Byzantine) and Western Roman empires paid him tributes to avoid his wrath.

The grave was discovered thanks to an excavation led by Polish Academy of Sciences archaeologist Jakub Niebylski. This site contained the remains of two boys aged between 7 and 9 years, buried alongside an assortment of grave goods and animal remains.

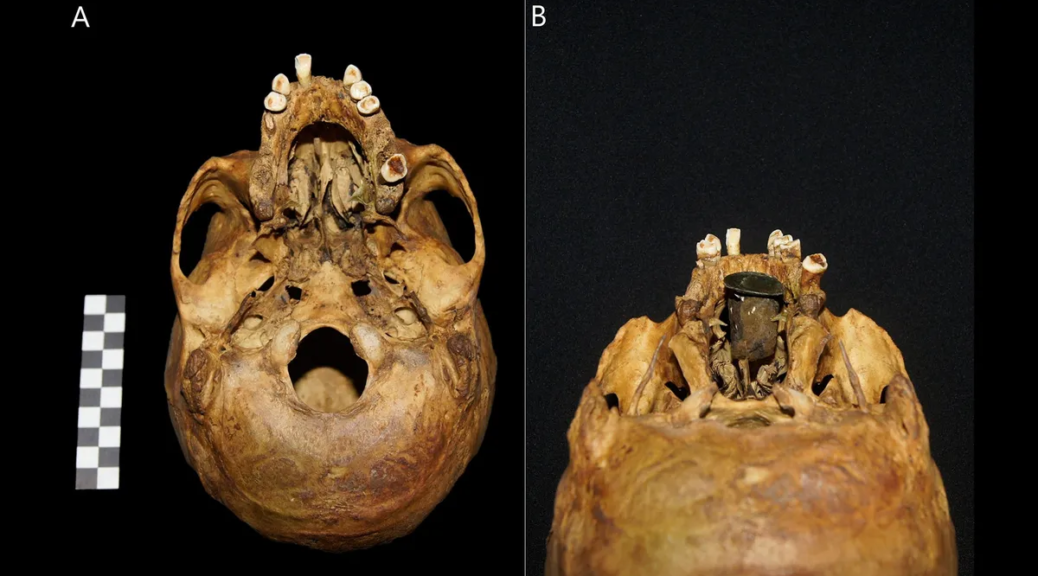

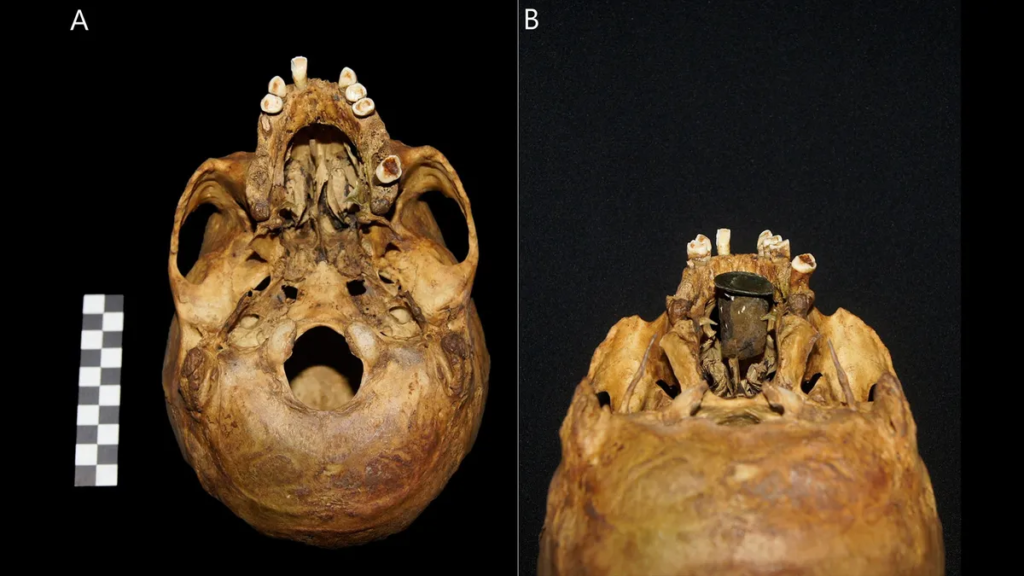

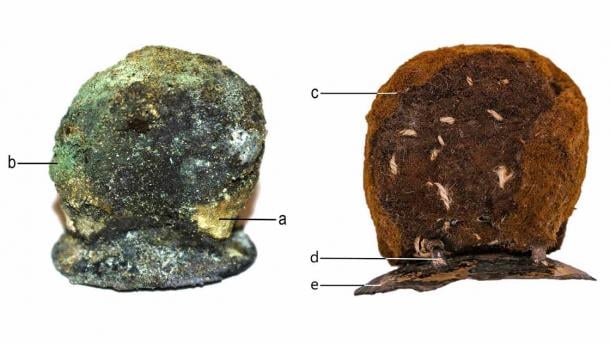

The grave contained numerous artifacts, including gold and silver trinkets, an iron knife, a clay pot, and the remains of various animals. Notably, one of the boys exhibited an artificially deformed skull, a practice common among Hunnic elites.

The Huns took up the practice of cranial deformation as a sign of aristocracy and elite status from the Alans, an ancient Iranian nomadic tribe. As a result, this burial site in Czulice provides a glimpse into the cultural practices and social hierarchies of the Huns, as well as their interactions with local populations during their migrations into Europe.

The boys’ bones were scattered in the oval-shaped grave, which was slightly over two feet below the surface. DNA testing revealed the boys’ separate ancestries. One boy, identified as Individual I, was of local European origin, likely connected to the Pannonian Plain in modern-day Hungary.

The other, identified as Individual II, was found to be of Hunnic origin and showed genetic similarities with modern Asian populations, especially nomads from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

The Hunnic boy’s remains were buried with several valuable items, including a gold earring, silver buckles, a clay vessel, and an iron knife, indicative of his high status. In contrast, the European boy, who lacked grave goods, was found buried on his stomach, suggesting a lower social status, possibly as a servant or companion to the Hunnic boy.

The double burial also included the remains of a dog, a cat, and a crow, which were thought to be the boys’ animal companions on their journey to the afterlife. This aspect of the burial is unusual for the Huns and may indicate a borrowing from Roman funerary practices.

More information about the lives and origins of the boys was discovered through isotope and ancient DNA testing, CT scans, X-rays, and further examination of the human bones.

The Hunnic boy’s lesions in his eye sockets suggested chronic anemia or another disease that may have contributed to his early death. Isotopic analysis of the boys’ diets indicated that both had protein-rich diets, but the lack of grave goods for the European boy hinted at his lower social status.

Scientists extracted and sequenced genes from the skeletons of the deceased and compared them with available genetic material. The genes have been deposited in a genetic database and will be compared with further material obtained from other graves across Europe.