2,500-Year-Old Bronze Items and Bones Recovered in Poland

Dozens of bronze ornaments: necklaces, bracelets, greaves, decorative pins, as well as numerous human bones, were discovered in the Chełmno district (Kujawy-Pomerania Province). According to archaeologists, these are the remains of sacrificial rituals from 2,500 years ago.

Today, the site of the discovery is a drained peat bog transformed into a farmland, but in the 6th century BCE it was a lake.

The discovery was made in the Chełmno Lake District by members of the Kujawy-Pomerania History Seekers Group, who conducted searches with metal detectors, with the permission of the Kujawy-Pomerania Province Conservator of Monuments in Toruń.

After being alerted by a group of detectorists, excavations led by Wojciech Sosnowski from the Office of Conservator of Monuments in Toruń began in January. They were carried out by researchers from the Institute of Archaeology of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń and the services of the Wda Landscape Park.

Sosnowski told PAP: “In the 6th century BCE, in the early Iron Age, ritual ceremonies were held here periodically.”

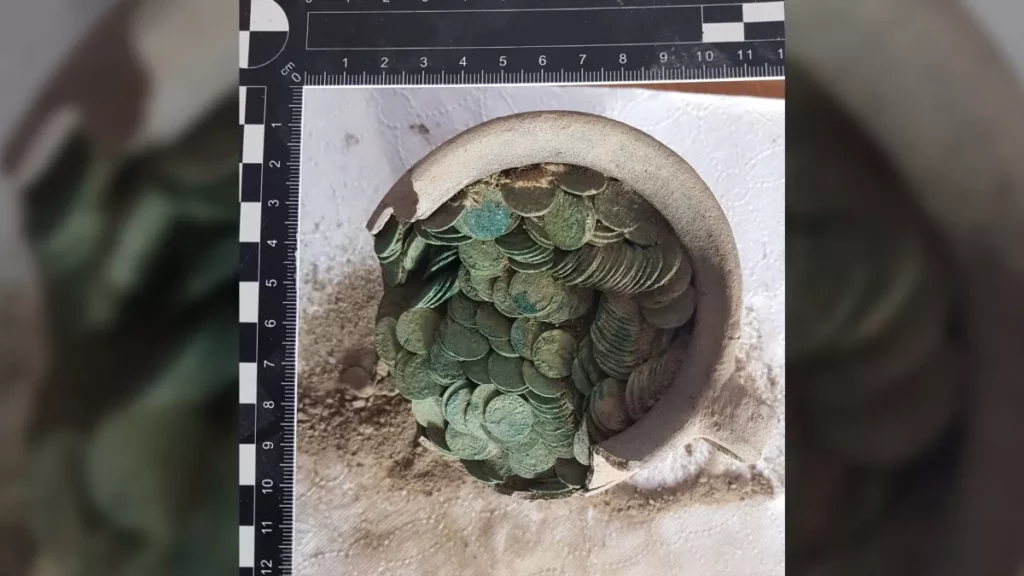

In addition to valuable items lying loosely in the ground, probably displaced as a result of ploughing, the researchers also found three deposits. These accumulations of monuments have remained in the same place since they were deposited 2.5 thousand years ago.

Sosnowski told PAP: “In the 6th century BCE, in the early Iron Age, ritual ceremonies were held here periodically.”

In addition to valuable items lying loosely in the ground, probably displaced as a result of ploughing, the researchers also found three deposits. These accumulations of monuments have remained in the same place since they were deposited 2.5 thousand years ago.

According to the researchers, most of the items discovered during the research project are whole or damaged ornaments: necklaces, bracelets, greaves, pins with spiral heads, probably made for ceremonial purposes.

Dr. Jacek Gackowski from the Institute of Archaeology of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, who analysed the artefacts said: “A particularly impressive object is a necklace consisting of many delicate metal and probably glass elements, decorated with a series of pendants in the shape of fish tails.”

The researchers also discovered metal parts of horse harnesses and a large number of other items. Among them there are very rarely preserved products made of organic raw materials – fabrics, antler tools in bronze sheet fittings and pieces of rope.

Most of the artefacts, according to the researchers, should be associated with the Lusatian culture. Several dozen kilometres further to the south-east, its representatives lived in the now famous fortified settlement in Biskupin. However, there are also objects that are foreign to this area and should be associated with the Scythian civilization and its influences from the area of today’s Ukraine.

Dr. Gackowski said: “This includes temple rings – unique objects of great scientific value, because they are – so far and in such numbers – the northernmost artefacts of this type discovered in Europe.”

The researchers were surprised to find many human bones among dozens of artefacts. This suggests that it was a place where sacrifices were probably made in prehistory, and not only of valuable items.

Why were people sacrificed? According to the researchers, this was related to the period of migrations and, probably, invasions.

Gackowski said: “It was a time of growing unrest related to the penetration of groups of nomads coming from the Pontic Steppe, probably Scythians or the Neuri, into Central and Eastern Europe.

“These people, probably in order to delay the rapid changes associated with the appearance of new neighbours with a completely different organization, appearance and vision of the world, began to practice various rituals treatments. They tried to secure their existence and give ritual resistance to the imminent, as it turned out, inevitable changes.”

To date, archaeologists have collected over a hundred human bone fragments. All the remains were on the surface of a freshly ploughed field.

“At the moment, it is difficult to estimate how many people we are dealing with. It will be determined by a thorough anthropological analysis,” said Mateusz Sosnowski, an archaeologist from the Wda Landscape Park, who participated in the field work.

For security reasons and fear of robbery, archaeologists have not yet revealed the exact location of the discovery.

The custom of sinking bronze products during that period is known from other areas of Europe. Treasures from the period are also discovered in Poland, but according to scientists analysing the collection, this is the first place in Poland where people were also sacrificed.

The community described by scientists as the Lusatian culture inhabited the Vistula and Oder river basins, as well as the areas of Saxony, Brandenburg, northern Bohemia and Lusatia. Its economy was mainly based on farming and breeding horned cattle, sheep, pigs and goats.

In the beginning of the Iron Age, in addition to open settlements, forts also appeared (existing from the 8th to the 6th century BCE), considered tribal centres or places of refuge during unrest. The bronze artefacts and offerings discovered by detectorists and archaeologists come from that period.