Centuries-old skeleton with massive, crippling bone growth unearthed in Portugal

A rare and gruesome bone growth protruding from a 14th to 19th-century woman’s thigh bone mushroomed after she suffered severe trauma, anthropologists in Portugal have found.

The 3-inch (8 centimeters) lump sprouted precisely where a muscle joins the inner thigh bone and the public bone together, which would have caused the woman debilitating pain and severely impaired mobility.

“I have never seen such [a] large bone formation,” lead author Sandra Assis, a biological anthropologist at the NOVA University Lisbon in Portugal, told Live Science in an email. “I was really intrigued by its morphology.”

The massive, “rope-like” bone spur probably formed on the woman’s femur as a result of a serious muscle injury, according to a study published Jan. 9, 2023 in the International Journal of Paleopathology.

The researchers think that this could be a rare form of bone growth called myositis ossificans traumatica, which can develop after a single traumatic accident or following multiple minor injuries.

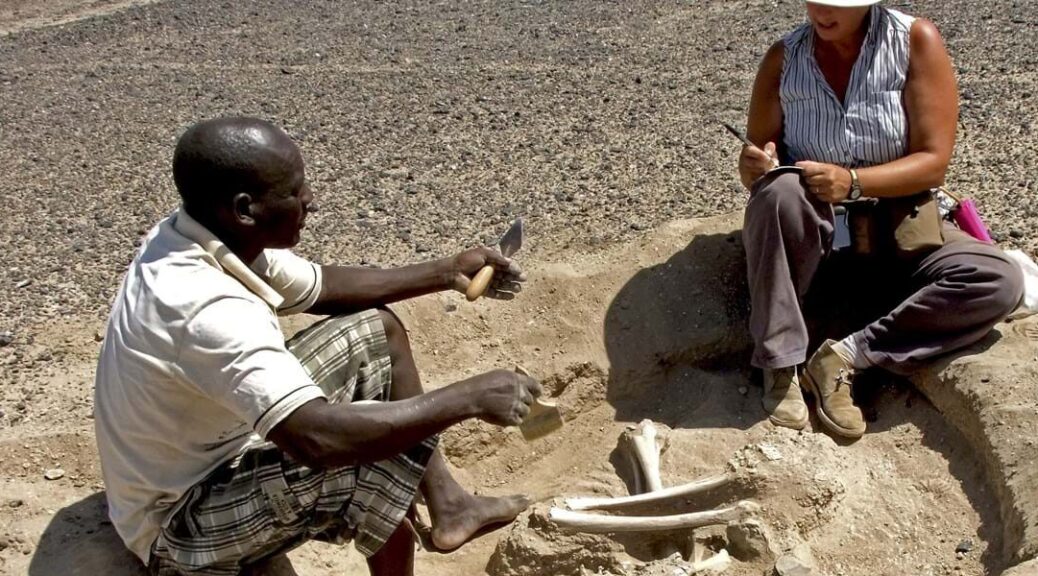

Archeologists unearthed the maimed woman’s skeleton in 2002 in the ancient necropolis of São Julião Church, in the village of Constância, Portugal. They discovered her remains among those 106 adults and 45 children who lived between 600 and 200 years ago.

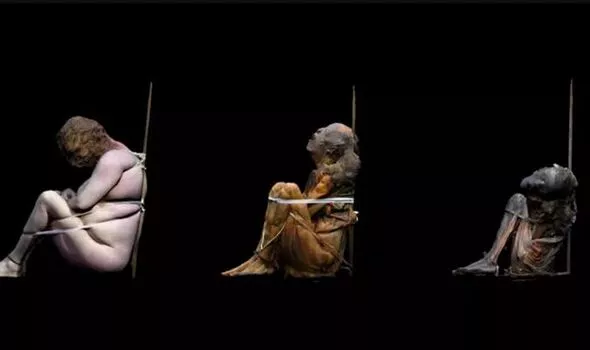

Although it was incomplete and missing the left femur, her skeleton was well preserved and indicated that she was roughly 5 feet tall (1.54 meters) and over 50 years old.

Archeologists found her on her back, with her hands resting on her pelvis, a coin on her left forearm and her head tilted to the right. Researchers later spotted the protruding lump of bone, while cleaning the skeleton in the laboratory, Assis said.

The researchers detected no fracture on the woman’s thigh bone and remain uncertain about what caused the grisly growth to sprout. They concluded that the injury was 6 weeks to a year old when she died and would have prevented the woman from making any dynamic movements or from carrying weight.

The gruesome bulge probably developed following a traumatic accident that crippled a muscle in the woman’s inner thigh called the pectineus.

This is the first time that paleopathologists document a case of this rare type of bone growth, known as myositis ossificans traumatica, affecting the pectineus muscle.

“The appearance of the femoral bone suggests a longstanding process,” Assis said. “We do not have the medical record of this female, but looking at similar clinical cases we can assume that this femoral lesion was quite debilitating.”

Nowadays, surgery can remove bone spurs, but that was not an option when the woman lived, Assis said.