Américas – Skeleton mystery solved: One-legged remains of Napoleon’s favorite general identified

DNA tests on a one-legged skeleton found under a dance floor in Russia have officially confirmed the identification of one of Napoleon’s favorite generals

In Smolensk, Russia, a team of French and Russic archeologists discovered the remains of General Charles-Étienne Gudin, one of Napoleon Bonaparte’s most admired military commanders.

The one-legged military man was killed by a cannonball when he was 44 on Aug. 22, 1812, according to LiveScience — and his remains were left buried until now.

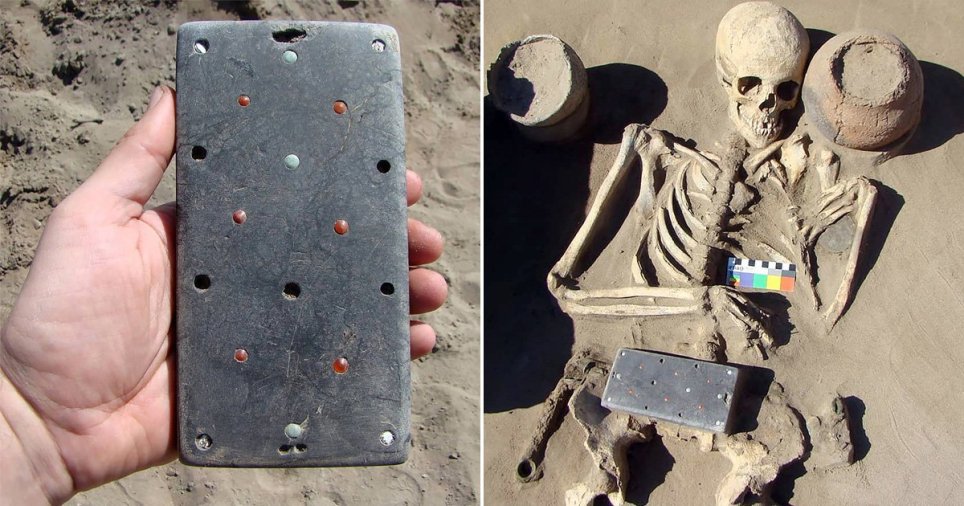

Found on July 6 beneath the foundations of a dancefloor, the skeleton was indeed missing a left leg and also showed evidence of injury on the right leg — two essential details that suggest that these remains, in fact, belong to Gudin.

Records from 1812 note that the man had his leg amputated below the knee after sustaining grievous harm during the Russian invasion. Upon his death, Napoleon ordered Gudin’s name to be inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe while his bust was put in the Palace of Versailles, and a Parisian street was named after him.

Meanwhile, his heart was removed and placed in a chapel in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery as a token of honor.

“It’s a historic moment not only for me but for our two countries,” said French historian and archaeologists Pierre Malinovsky, who helped find Gudin’s remains.

“Napoleon was one of the last people to see him alive, which is very important, and he’s the first general from the Napoleonic period that we have found.”

Bonaparte and Gudin were childhood friends and attended the Military School in Brienne together. Gudin’s death had a profound impact on his old friend. Napoleon reportedly cried when he heard the news and immediately ordered that the man receive high honors.

In July, the research team eagerly planned on testing the skeleton for DNA to officially lay all doubt about its identification to rest, Reuters reported.

“It’s possible that we’ll have to identify the remains with the aid of a DNA test which could take from several months to a year,” the Russian military-historical society explained. “The general’s descendants are following the news.”

According to CNN, Malinovsky has since eradicated any uncertainty. In November 2019, he revealed that he transported part of the skeleton’s femur and several teeth from Moscow to Marseille shortly after the excavation to conduct a detailed analysis.

The overnight trip concluded with a genetic comparison between the remains and that of the deceased general’s mother, brother, and son.

The resourceful scientist had simply packed the bone and teeth in his luggage to do so. The results were satisfactory, to say the least.

“A professor in Marseille carried out extensive testing and the DNA matches 100 percent,” he said. “It was worth the trouble.”

Malinovski said Gudin will likely be buried at Les Invalides. The historic compound of military monuments and museums will see the one-legged general in good company — as it also holds the body of Napoleon, himself.