Scientists discover intact Ice Age woolly rhino in Siberia

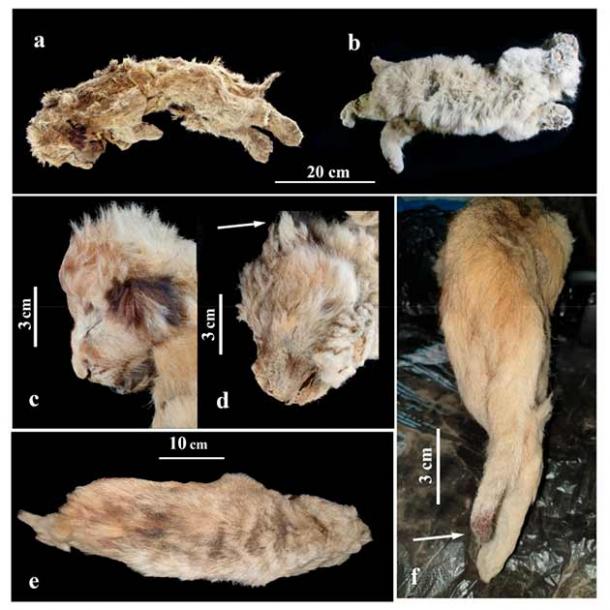

Russian researchers have just announced the discovery of a remarkably well-preserved woolly rhinoceros that was excavated in August 2020.

According to The Siberian Times, the specimen is between 20,000 and 50,000 years old, and was found in such pristine condition that much of its internal organs were still intact. Some are calling this the best-preserved carcass of its kind.

The frozen Siberian tundra offers the perfect conditions to preserve Ice Age remnants like this, while climate change has seen a slew of them melt to the surface. In recent years, experts in Yakutia, Siberia have excavated everything from ancient lion cubs and bison to a horse and woolly mammoths.

Scientists estimate that this latest discovery is about 80 percent undamaged. Indeed, all of its limbs, fur, and most of its teeth remain intact. Scientists are even confident that they can determine the creature’s last meal.

“The young rhino was between three and four years old and lived separately from its mother when it died, most likely by drowning,” said Dr. Valery Plotnikov from Yakutia’s Academy of Sciences. “The gender of the animal is still unknown… The rhino has a very thick short underfur, very likely it died in the summer.”

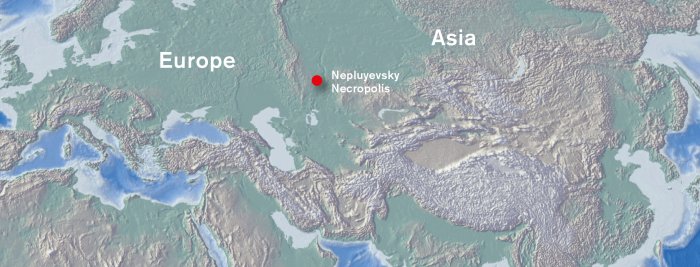

The specimen was unearthed not too far from where Sasha, the world’s only baby woolly rhino, was discovered in 2014. Sasha is believed to be about 34,000 years old and was around seven months old when she died.

Sasha’s discovery first showed scientists that even baby woolly rhinos had fur, and this latest discovery has only strengthened that theory.

“We have learned that woolly rhinoceroses were covered in very thick hair,” said Dr. Plotnikov of Sasha. “Previously, we could judge this only from rock paintings discovered in France. Now, judging by the thick coat with the undercoat, we can conclude that the rhinoceroses were fully adapted to the cold climate from a young age.”

As it stands, researchers have been unable to further analyze this latest specimen until stable ice roads can form for them to travel back to Yakutia’s capital of Yakutsk.

Discovered downstream of Tirekhtyakh River, finding the rhino wasn’t a cakewalk, as transportation across Yakutia’s utterly vast and remote territory is incredibly treacherous. Even in the summer, many areas are only accessible by air or boat.

In the winter, however, a rather practical network of ice roads forms, which allows people to travel across the tundra.

Despite having to wait for those roads to form in order to properly assess the specimen, Dr. Plotnikov and his team have already gleaned much from the find.

The horns of this creature, for instance, have suggested that this particular species of woolly rhino foraged for food. The fact that the animal’s internal organs remain intact will also show the scientists a lot about how this prehistoric creature lived.

“There are soft tissues in the back of the carcass, possibly genitals and part of the intestine,” said Dr. Plotnikov. “This makes it possible to study the excreta, while will allow us to reconstruct the paleoenvironment of that period.”

Yakutia is a remarkably fertile place for those in search of Ice Age animals. In just the last few years, researchers have found ancient wolf pups, “pygmy” mammoths, birds, foals, and more. Just this past summer, an Ice Age wolf pup was discovered with the remains of what could have been one of the last woolly rhinos on Earth in its stomach.

As for this latest woolly rhino, it will ultimately be transported to Sweden where researchers have been working to sequence the genomes of several species of prehistoric rhinos.