1,000-year-old cross buried in Scottish field thought to have belonged to the king

Since painstaking restoration, a stunning Anglo-Saxon silver cross has arisen from under 1,000 years of encrusted dirt. Such is its quality that whoever commissioned this treasure may have been a high-standing cleric or even a king.

It was a sorry-looking object when first unearthed in 2014 from a ploughed field in western Scotland as part of the Galloway Hoard, the richest collection of rare and unique Viking-age objects ever found in Britain or Ireland, acquired by the National Museums Scotland (NMS)

The tiniest glimpses of its gold-leaf decoration could be spotted through its grubby exterior, but its stunning, intricate design had been concealed until now. A supreme example of Anglo-Saxon metalwork has been revealed.

The equal-armed cross was created by a goldsmith of outstanding skill and artistry. Its four arms bear the symbols of the four evangelists to whom tradition attributed the gospels of the New Testament: Saint Matthew (man), Mark (lion), Luke (cow) and John (eagle).

Dr Martin Goldberg, the NMS principal curator of early medieval and Viking collections, recalled his “wonderment” after seeing the cross in a gleaming state.

He told the Observer: “It’s just spectacular. There really isn’t a parallel. That is partly because of the time period it comes from. We imagine that a lot of ecclesiastical treasures were robbed from monasteries – that’s what the historical record of the Viking age describes to us. This is one of the survivals. The quality of the workmanship is just incredible. It’s a real privilege to see this after 1,000 years.”

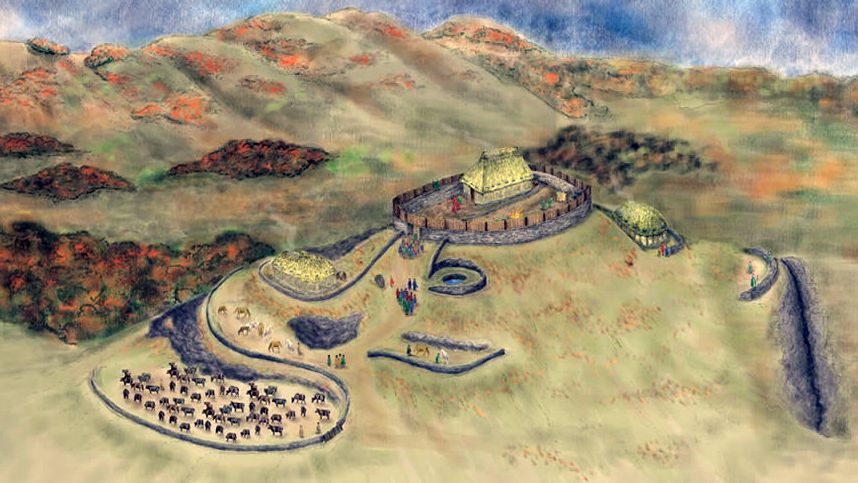

The Galloway Hoard was buried in the late 9th century in Dumfries and Galloway, where it was unearthed by a metal detectorist in 2014.

The cross was among more than 100 gold, silver and other items, including a beautiful gold bird-shaped pin and a silver-gilt vessel. Incredibly, textile in which the objects had been wrapped was among organic matter that also survived.

Goldberg said: “At the start of the 10th century, new kingdoms were emerging in response to Viking invasions. Alfred the Great’s dynasty was laying the foundations of medieval England, and Alba, the kingdom that became medieval Scotland, is first mentioned in historical sources.”

Galloway had been part of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, said Goldberg, and was called the Saxon coast in the Irish chronicles as late as the 10th century. But this area was to become the Lordship of Galloway, named from the Gall-Gaedil, people of Scandinavian descent who spoke Gaelic and dominated the Irish Sea zone during the Viking age.

“The mixed material of the Galloway Hoard exemplifies this dynamic political and cultural environment,” Goldberg added.

“The cleaning has revealed that the cross, made in the 9th century, [has] a late Anglo-Saxon style of decoration. This looks like the type of thing that would be commissioned at the highest levels of society. First sons were usually kings and lords, second sons would become high-ranking clerics. It’s likely to come from one of these aristocratic families.”

The pectoral cross has survived with its intricate spiral chain, from which it would have been suspended from the neck, displayed across the chest.

The chain shows that the cross was worn. Goldberg said: “You could almost imagine someone taking it off their neck and wrapping the chain around it to bury it in the ground. It has that kind of personal touch.”

Conservators carved a porcupine quill to create a tool that was sharp enough to remove the dirt, yet soft enough not to damage the metalwork.

Dr Leslie Webster, former keeper of Britain, Prehistory and Europe at the British Museum, said: “It is a unique survival of high-status Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical metalwork from a period when – in part, thanks to the Viking raids – so much has been lost.”

Why the hoard was buried remains a mystery. Goldberg said that the cross now raises many more questions and that research continues.

The exhibition, Galloway Hoard: Viking-age Treasure, will be at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.