Nazca Line Discoveries in Peru Suggest the Mysterious Geoglyphs Are Pervasive

In Peru, the Nazca Lines are the most mysterious archeological geoglyphs. For nearly a century, these humanoid, geometric forms and animal glyphs have confused experts.

Scientists from Japan now claim that up to 143 new images have been found near the UNESCO World Heritage site. One was discovered using new artificial intelligence and it is believed that this technology could now reveal a flood of more glyphs.

The Nazca Lines have been studied since 2004 by a group from Yamagata University in Japan headed by Prof. Masato Sakais, a specialist in Andean archeology.

They suspected that there were new geoglyphs still to be discovered. This was “based on an on-site investigation begun in 2010 as well as aerial pictures” reports Asahi.com. The Nazca Lines are on a plateau on the pampa and are some 250 miles (80 kilometers) south of Lima the capital of Peru.

A press release from IBM Research describes the manmade phenomena as “shapes of varying complexity – from simple geometric shapes and plants to zoomorphic designs of animals — some several hundreds of meters in length, etched into the terrain”.

The lines date from anywhere between 500 BC to 500 AD and they were created by pre-Incan people. They were possibly used as solar calendars or more likely for ceremonial purposes and many can be considered to be ritual art.

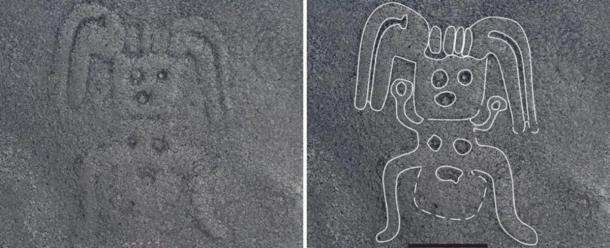

Asahi.com reports that “until now, it was thought that 80 or so geoglyphs exist”. However, the team from Yamagata University used drones and 3D data to identify up to 143 new geoglyphs. According to a press release by Yamagata University, ‘these geoglyphs depicted people and many different animals (including birds, monkeys, fish, snakes, foxes, felines, and camelids). One of the new images “shows a two-headed snake that appears to be devouring two people”.

The geoglyphs are of two types, depending on how they were made. The first category comes from the Early Nazca Period and consists of images made by removing black topsoil to reveal white sand.

The second type which was created somewhat later was made by placing earth and stones on the surface. It seems that some of the first types were used for ceremonial purposes and the second type was “produced beside paths or on sloping inclines and are thought to have been used as way posts when traveling” according to Yamagata University.

However, the Japanese team was faced with a number of challenges. They could not manage all the data that they retrieved. So the team and their faculty entered into an academic partnership with IBM Japan Ltd to exploit the tech company’s “extensive initiatives to analyze and leverage large, complex data sets, such as remote sensing and geographical data, with AI” reports Yamagata University.

Yamagata archaeologists collaborated closely with IBM researchers, after a feasibility study that demonstrated the company’s Watson Machine Learning Community Edition, could help in identifying glyphs.

They utilized IBM PAIRS Geoscope, when they surveyed the Nazca Pampa, recently. This is a cloud-based Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology that can analyze data from multiple datasets and is especially useful when it comes to geospatial evaluations.

The team used LiDAR, that uses lasers to make a 3D representation of the lines in the desert. They also used images from satellites and drones.

Data from on-the-ground geographical surveys were all collected. All this diverse data was inputted into PAIRS and its AI was able to integrate and evaluate the data in a matter of minutes where previously such an analysis would have taken months.

The researchers found a 15 foot (5 meters) long geoglyph of a humanoid figure. This figure appears to be “brandishing some form of the club” reports Fox News. Furthermore, “AI analysis of aerial footage indicated there are more than 500 other candidate sites” reports Ashai.com. One of these was subsequently proven to be a site of ritual art.

These finds are important in themselves but also demonstrated how AI could be used to speed up the process of identifying new Nazca Lines.

The new technology will be used along with fieldwork to further study the images that have been found. This will result in a map of the new geoglyphs and will help in the development of a comprehensive map for the entire location.

Not only can they help to locate new Nazca Lines, but IBMs technology can also help to preserve the UNESCO World Heritage site. “Professor Sakai and others have carried out activities to preserve this heritage site” in recent years report Yamagata University.

The mysterious glyphs are being threatened by the growth of nearby urban areas. It is hoped that AI technology can also play a part in determining the distribution of the lines so that they can be better protected.