9,500-Year-Old Baskets And 6,200-Year-Old Sandals Found In Spanish Cave

Scientists have discovered and analyzed the first direct evidence of basketry among hunter-gatherer societies and early farmers in southern Europe (9,500 and 6,200 years ago), in the Cueva de los Murciélagos of Albuñol (Granada, Spain).

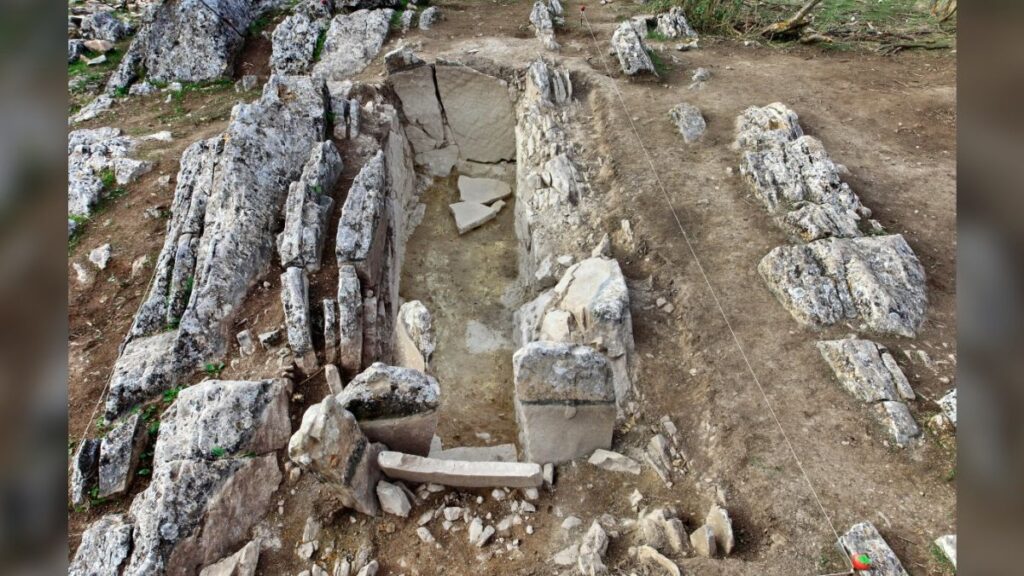

This site is one of the most emblematic archaeological sites of prehistoric times in the Iberian Peninsula due to the unique preservation of organic materials found there.

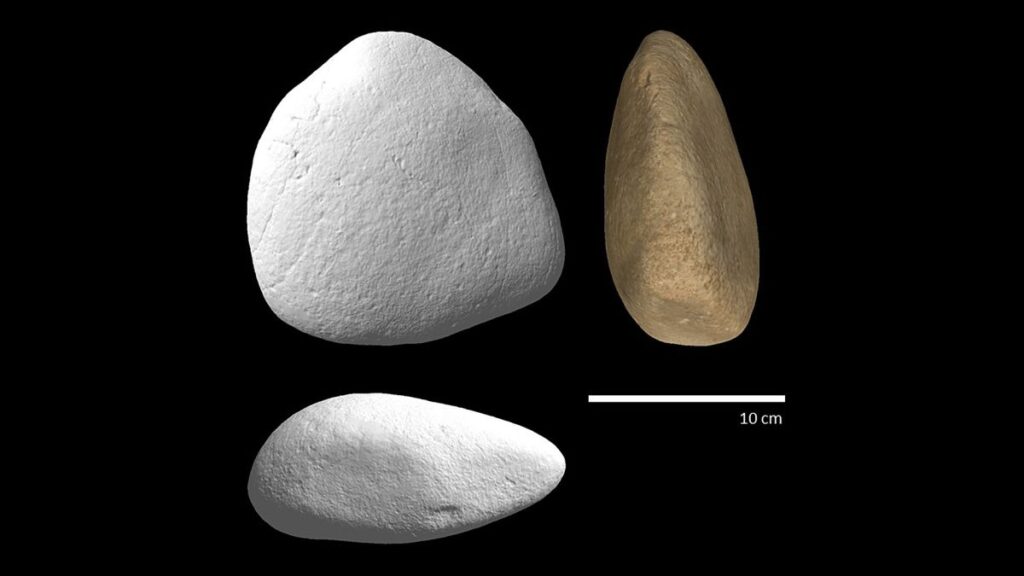

The work analyzes 76 objects made of organic materials (wood, reed and esparto) discovered during 19th century mining activities in the Granada cave.

The researchers studied the raw materials and technology and carried out carbon-14 dating, which revealed that the set dates to the early and middle Holocene period, between 9,500 and 6,200 years ago.

This is the first direct evidence of basketry made by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies in southern Europe and a unique set of other organic tools associated with early Neolithic farming communities, such as sandals and a wooden mace.

As researcher of the Prehistory Department of the University of Alcalá Francisco Martínez Sevilla explains, “the new dating of the esparto baskets from the Cueva de los Murciélagos of Albuñol opens a window of opportunity to understanding the last hunter-gatherer societies of the early Holocene.”

“The quality and technological complexity of the basketry makes us question the simplistic assumptions we have about human communities prior to the arrival of agriculture in southern Europe. This work and the project that is being developed places the Cueva de los Murciélagos as a unique site in Europe to study the organic materials of prehistoric populations.”

Cueva de los Murciélagos is located on the coast of Granada, to the south of the Sierra Nevada and 2 kilometers from the town of Albuñol. The cave opens on the right side of the Barranco de las Angosturas, at an altitude of 450 meters above sea level and about 7 kilometers from the current coastline. It is one of the most emblematic prehistoric archaeological sites of the Iberian Peninsula due to the rare preservation of organic materials, which until this study had only been attributed to the Neolithic.

The objects made of perishable materials were discovered by the mining activities of the 19th century and were documented and recovered by Manuel de Góngora y Martínez, later becoming part of the first collections of the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid.

As detailed by María Herrero Otal, co-author of the work and researcher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, “The esparto grass objects from Cueva de los Murciélagos are the oldest and best-preserved set of plant fiber materials in southern Europe so far known.”

“The technological diversity and the treatment of the raw material documented demonstrates the ability of prehistoric communities to master this type of craftsmanship, at least since 9,500 years ago, in the Mesolithic period.

Only one type of technique related to hunter-gatherers has been identified, while the typological, technological and treatment range of esparto grass was extended during the Neolithic from 7,200 to 6,200 years before the present.”

The work is part of the project “De los museos al territorio: actualizando el estudio de la Cueva de los Murciélagos de Albuñol (Granada)” (MUTERMUR). The objective of this project is the holistic study of the site and its material record, applying the latest archaeometric techniques and generating quality scientific data.

The project also included the collaboration of the National Archaeological Museum, the Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Granada, the City Council of Albuñol and the owners of the cave.

“The results of this work and the finding of the oldest basketry in southern Europe give more meaning, if possible, to the phrase written by Manuel de Góngora in his work Prehistoric Antiquities of Andalusia (1868): ‘the now forever famous Cueva de los Murciélagos’,” the authors say.

The study was conducted by a team of scientists led by researchers from the Universidad de Alcalá (UAH) and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), and published in the journal Science Advances.