Smoke archeology finds evidence Humans visited Nerja Cave for 40,000 years

A new study by a team from the University of Córdoba reveals that Nerja is the European cave with the most confirmed and recurrent visits during Prehistory.

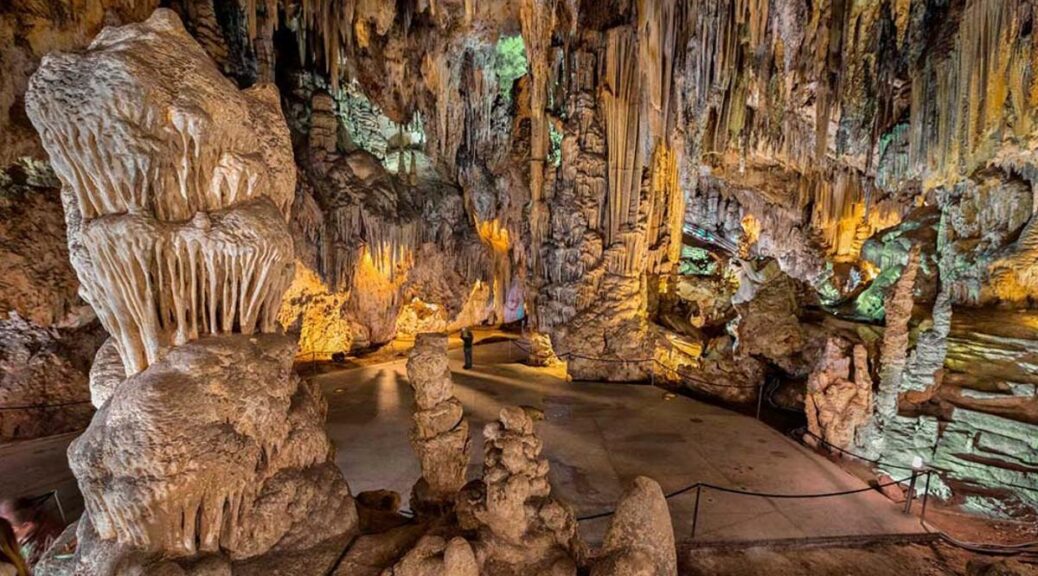

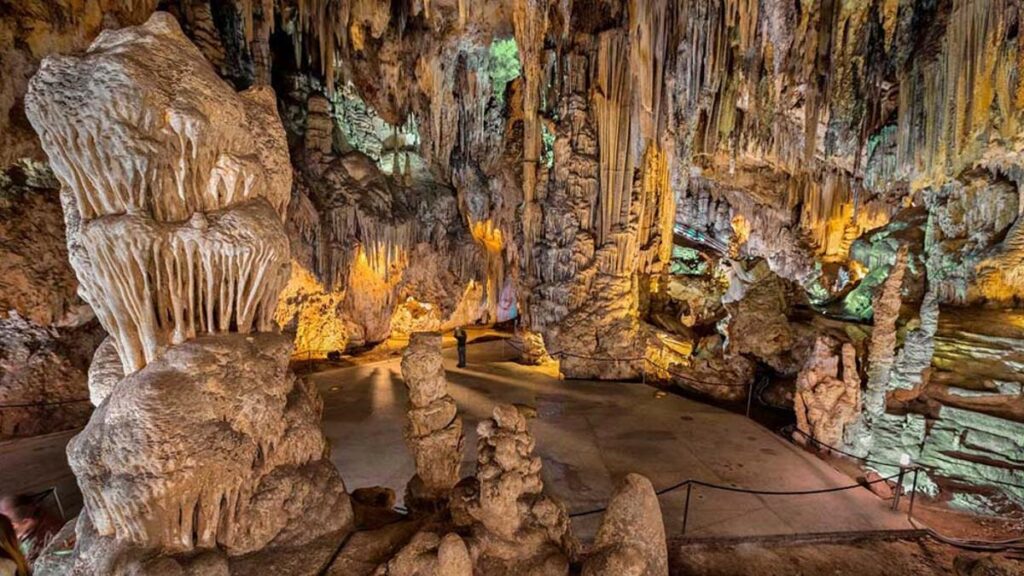

Humans have been visiting the Cave of Nerja for 41,000 years; for a few of them, it has been exploited as a tourist attraction, and for nearly the same amount of time, it has been the subject of scientific study.

Throughout its history, and even today, it continues to stun visitors and researchers from around the world.

The latest surprise from the cave, located in the province of Malaga, was just published in Scientific Reports by an international team including researchers from the University of Córdoba; Marian Medina, currently at the University of Bourdeux; Eva Rodríguez; and José Luis Sachidrián, a Professor of Prehistory and the scientific director of the Cave of Nerja.

They have managed to demonstrate that Humanity has been present in Nerja for some 41,000 years, 10,000 years earlier than previously believed, and that it is Europe’s cave featuring Paleolithic Art in Europe with the highest number of confirmed and recurrent visits to its interior during Prehistory.

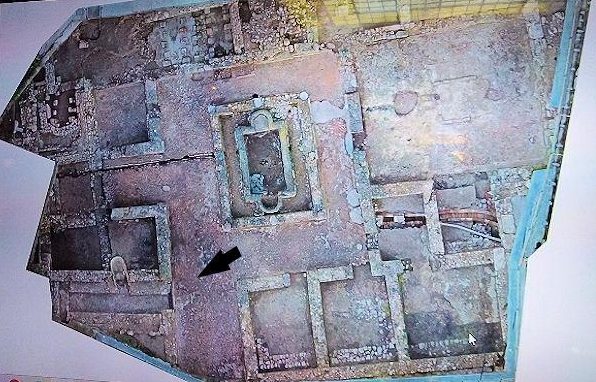

This new research has managed to document 35,000 years of visits in 73 different phases, which means that human groups entered the cave every 35 years, according to their calculations.

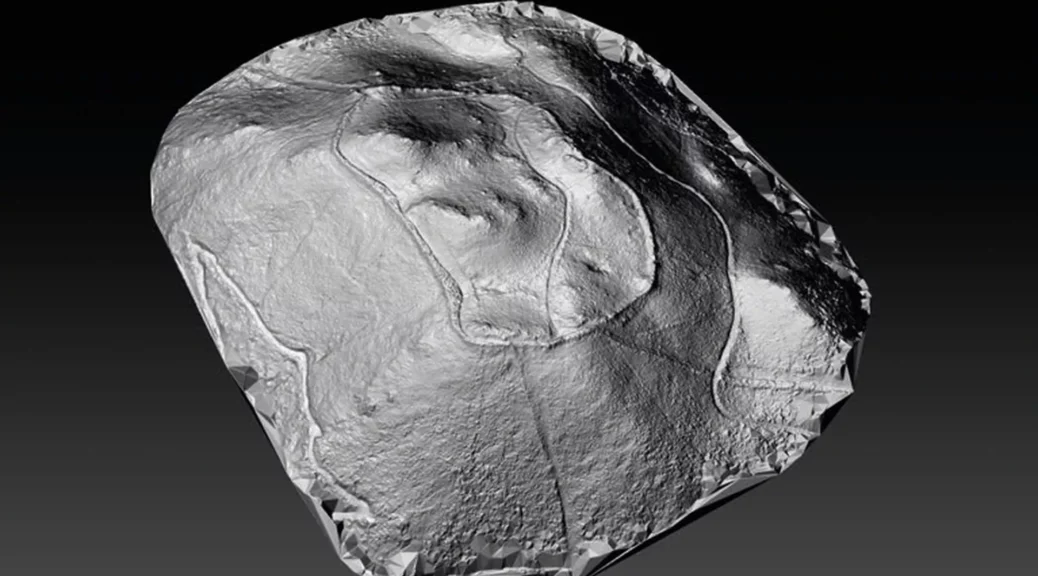

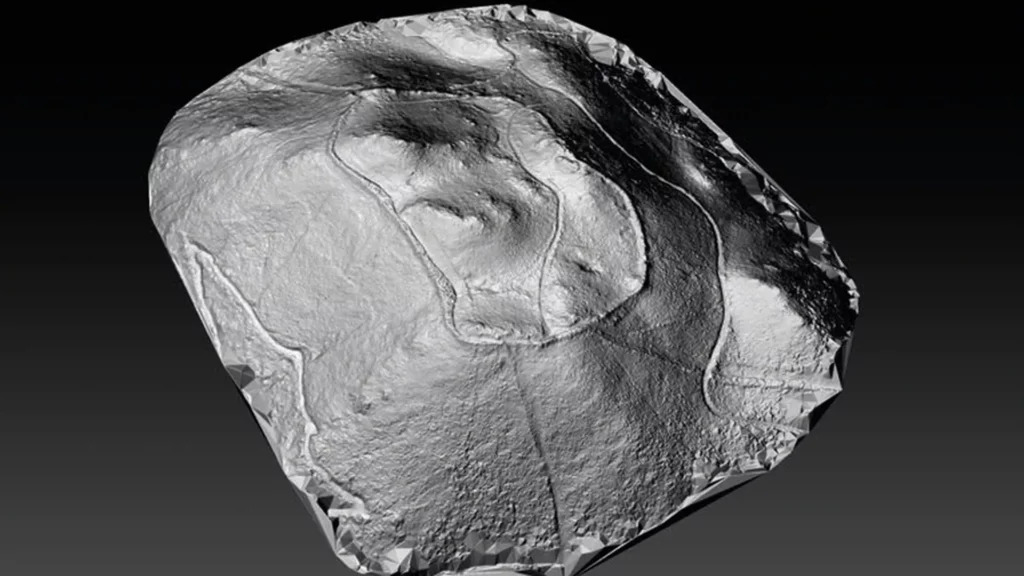

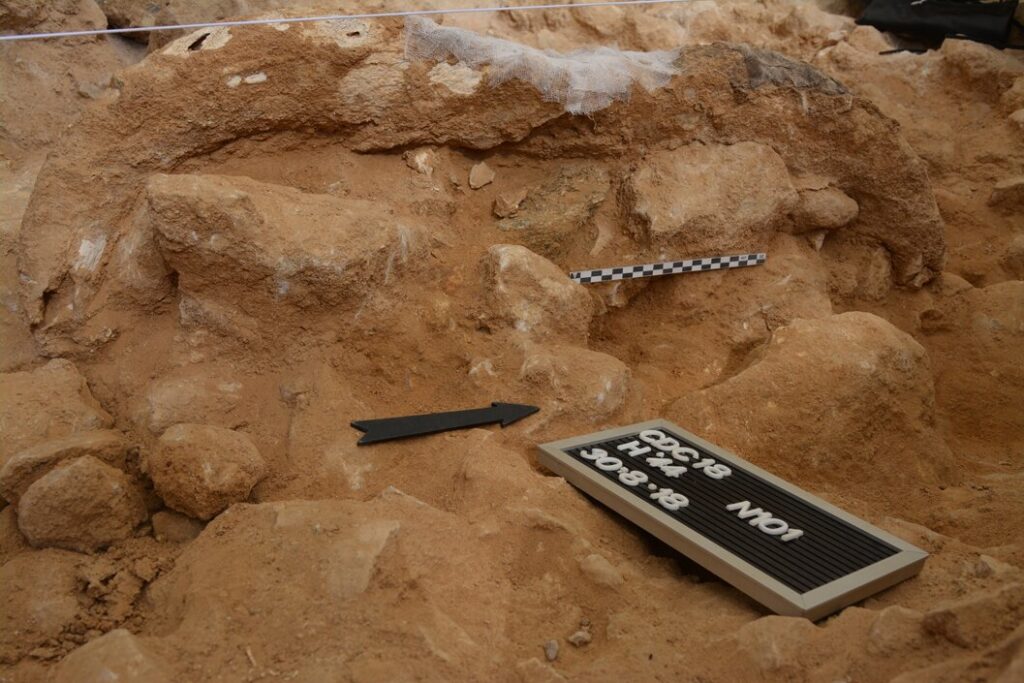

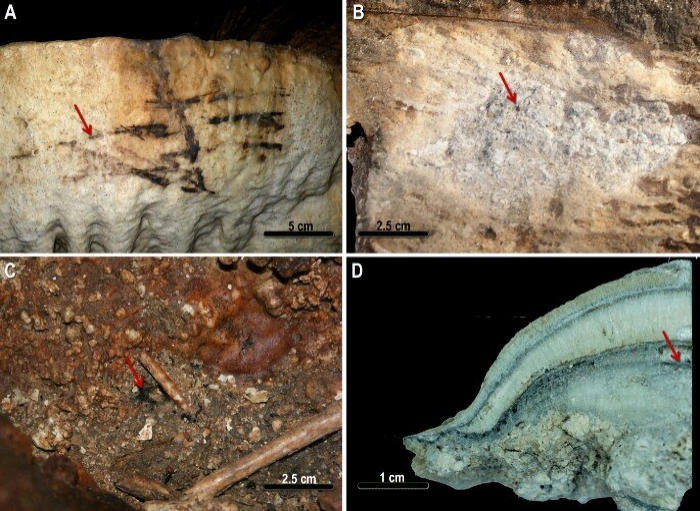

This level of precision has been made possible thanks to the use of the latest techniques dating the coals and remains of fossilized soot on the stalagmites of the Nerja Cave.

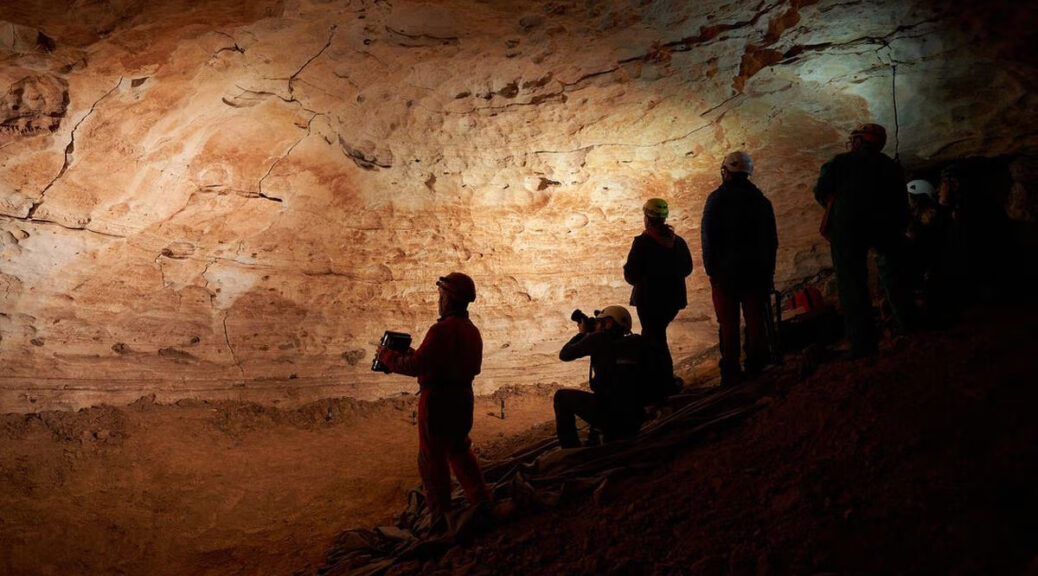

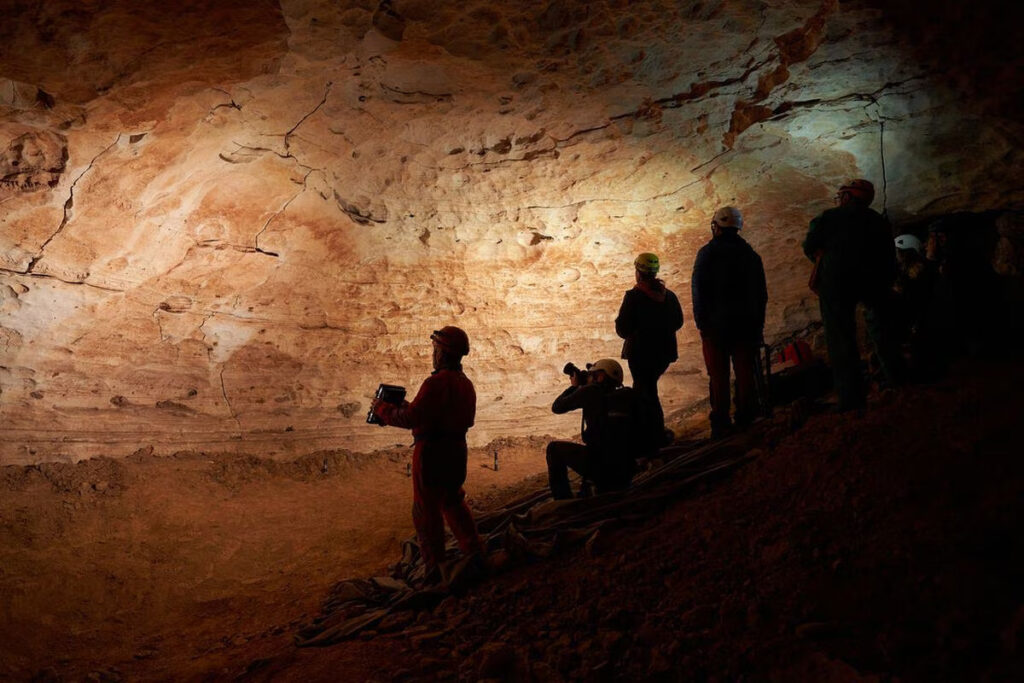

This is what has been called “smoke archaeology,” a new technique developed by the main author of the work, Marián Medina, from Córdoba’s Santa Rosa district, an honorary researcher at that city’s university, who has been reconstructing European prehistory for more than a decade by analyzing the remnants of torches, fires, and smoke in Spanish and French caves.

With the enthusiasm of one who loves what she does, Medina explains that the information that Transmission Electron Microscopy and Carbon-14 dating techniques can provide on man’s rituals and ways of life is impressive.

In this last work, 68 datings are presented, 48 totally new, of the deepest areas of the cave, featuring Paleolithic Art, and evidence of chronocultures never previously recorded has been found.

Furthermore, these “fire archaeologists” understand how to interpret the way the torches were moved based on the information detected under the microscope, inferring from it the symbolic and scenographic use that humans made of fire 40,000 years ago.

“The prehistoric paintings were viewed in the flickering light of the flames, which could give the figures a certain sense of movement and warmth,” explains Medina, who also underscores the funerary use of the Nerja Cave in the latter part of Prehistory, for thousands of years. “There is still much it can reveal about what we were like,” she says.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.