In Madrid, a 76,000-year-old Neanderthal hunting camp was discovered

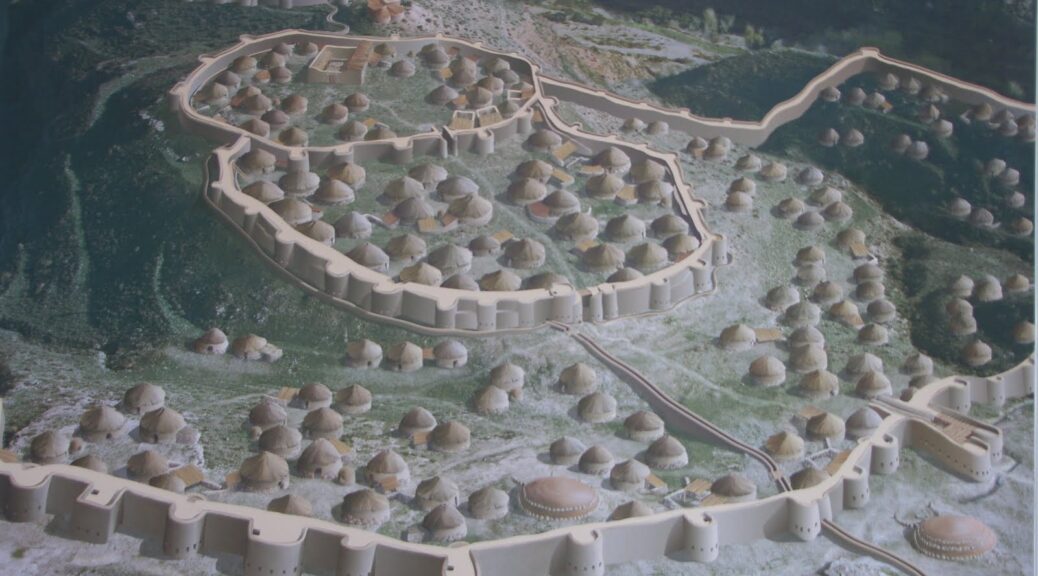

In Madrid, archaeologists have uncovered an ancient camp where Neanderthals conducted ‘hunting parties’ 76,000 years ago to chase down big bovids and deer. Archaeologists think it is the largest such camp in the Iberian Peninsula region, with a total area of 3,200 square feet (300 square meters).

They think it may have acted as an intermediary between Neanderthals hunting their prey and the place of final consumption, where the whole group would take advantage of the resources that the hunting parties had gathered.

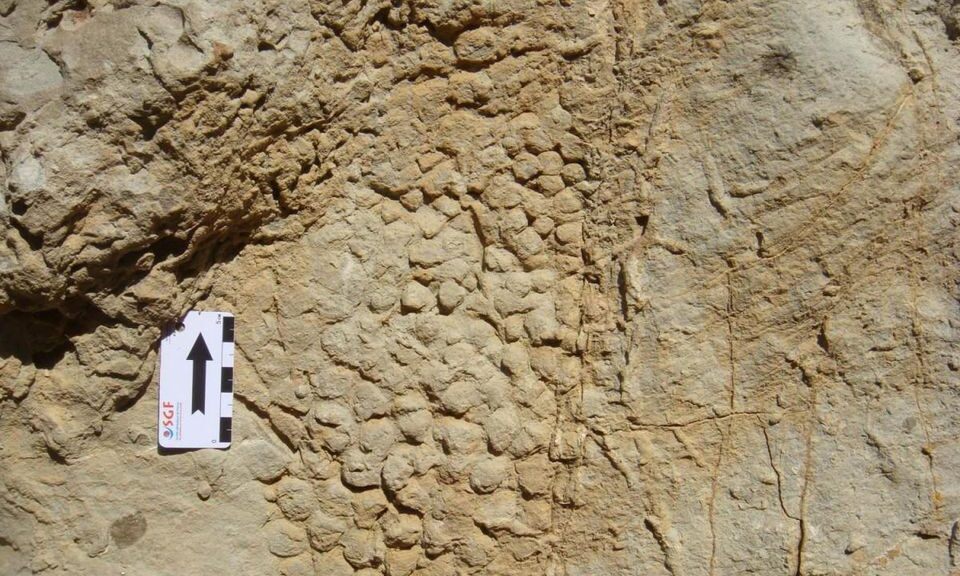

An analysis of fauna at the Abrigo de Navalmaíllo site in Pinilla del Valle, Madrid helped researchers make the discovery.

This looks at the entire process of what happens after an organism dies and eventually becomes a fossil.

‘We have been able to demonstrate with great certainty that the Neanderthals of Navalmaíllo hunted mainly large bovids and deer that they processed at the site and that they would later move to a second referential place,’ said Abel Moclán, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the National Center for Research on Human Evolution.

‘This aspect is very interesting since there are very few deposits in the Iberian Peninsula where this type of behaviour has been identified.

‘For all this, we have used very powerful statistical tools, such as Artificial Intelligence.’

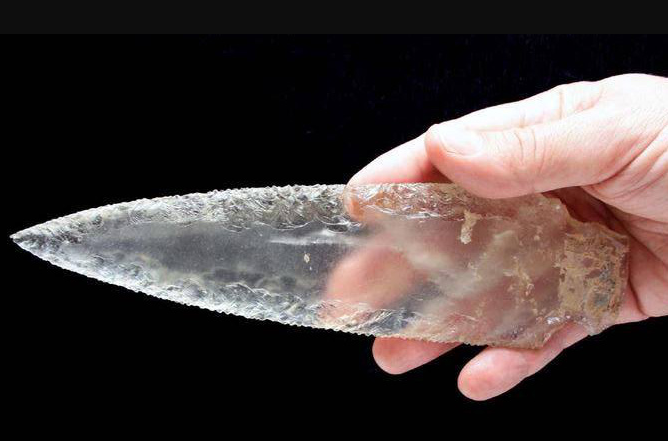

Archaeologists have previously found evidence of other Neanderthal activity in the region, including the making of stone tools or the use of fire.

With this latest discovery, researchers think it was used as a short-term base by Neanderthal groups.

Animals were captured locally, transported to the camp, and following their processing, parts of them would have been transported elsewhere.

All phases of butchery were identified, along with the extraction of marrow from long bones, revealing an interest in obtaining this nutritious food.

Human use of animal resources at the site reflects a focus on hunting large bovids and cervids, or deer, while horses, rhinoceroses and small-sized animals were much less frequent, the researchers said.

The activity of carnivores was also identified, but these animals, including hyenas, mostly left behind the remains of small prey or fed upon carcasses abandoned at the camp by human hunters.

‘Navalmaíllo is one of the few archaeological sites in Iberia that can be interpreted as a hunting camp,’ the study’s authors said, but added that ‘it is probable that more hunting camps are present in the Iberian Peninsula but are yet to be found.’

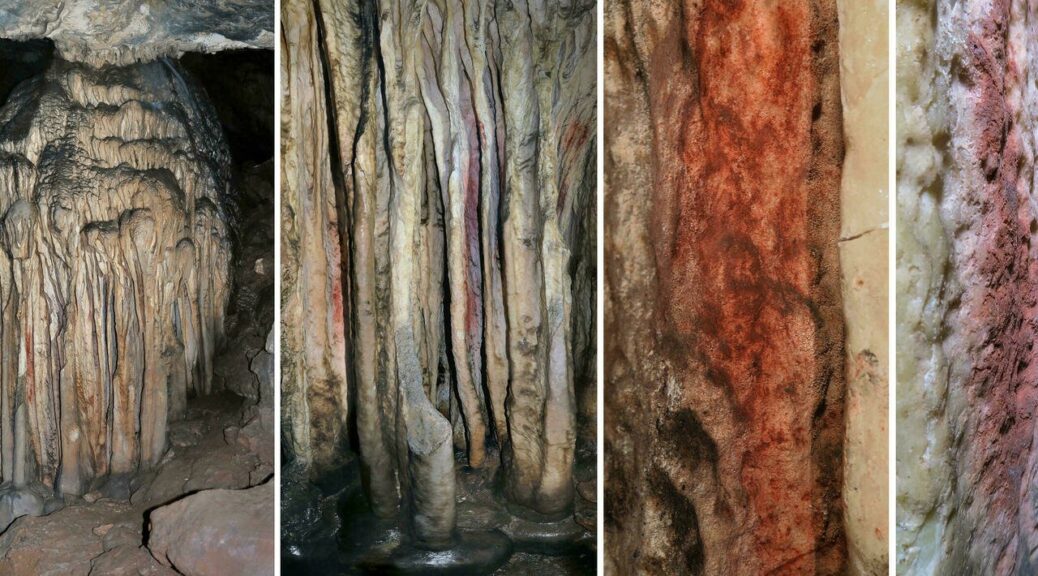

Earlier this month separate research claimed that cave paintings drawn by Neanderthals of swirling dots, ladders, animals and hands show our distant cousins were more artistic than first thought.

A flowstone formation at the Cueva de Ardales, Málaga in Spain is stained red, originally thought to be a natural coating of iron oxide deposited by flowing water.

However, samples of the red residue allowed a team from Barcelona University to re-examine its origins and confirm it was created by Neanderthals 65,000 years ago.

They found the ochre-based pigment was intentionally applied by Neanderthals, as modern humans had yet to make their appearance on the European continent.