Archaeology dig in Spain yields prehistoric ‘crystal weapons’

When you see a beautiful crystal how do you feel? Perhaps the perfection of the diamond or the vivid colours of the different gems are your thing? The fact is that people have been fascinated by crystals ever since they had first discovered them.

The gems ‘ names come from ancient cultures that were obsessed with them pretty much, adding them to their jewellery, kitchenware, and weapons. Do you know that even the Bible describes the new Jerusalem after the apocalypse built all in gems and crystals?

An archaeological excavation in Spain reveals that even in the 3rd millennium BC, crystals were an object of fascination and ritual

Archaeologists discovered a number of shrouds decorated with amber beads at the Valencina de la Concepción site, and they also found a “remarkable set of “crystal weapons.

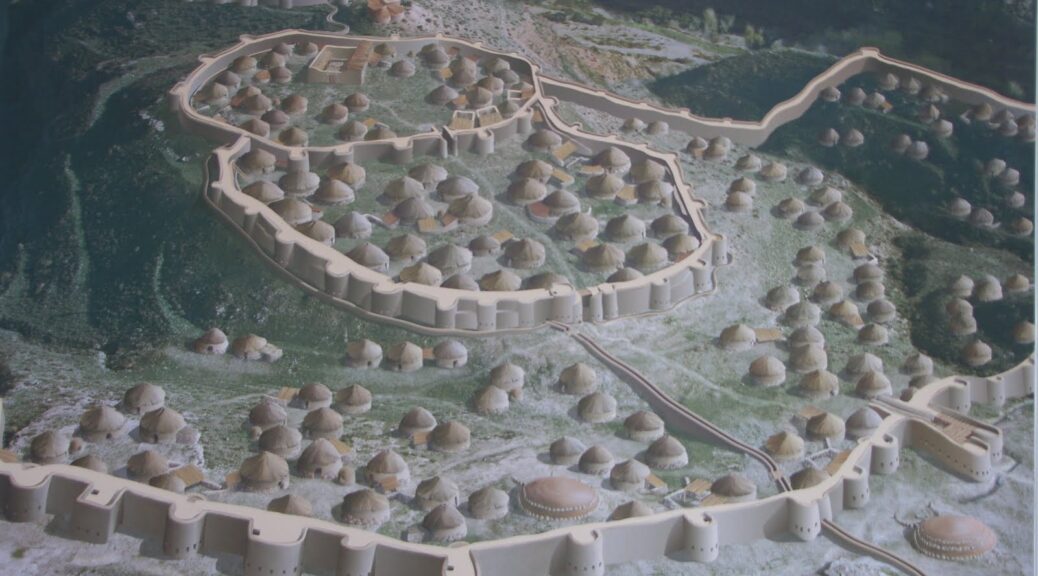

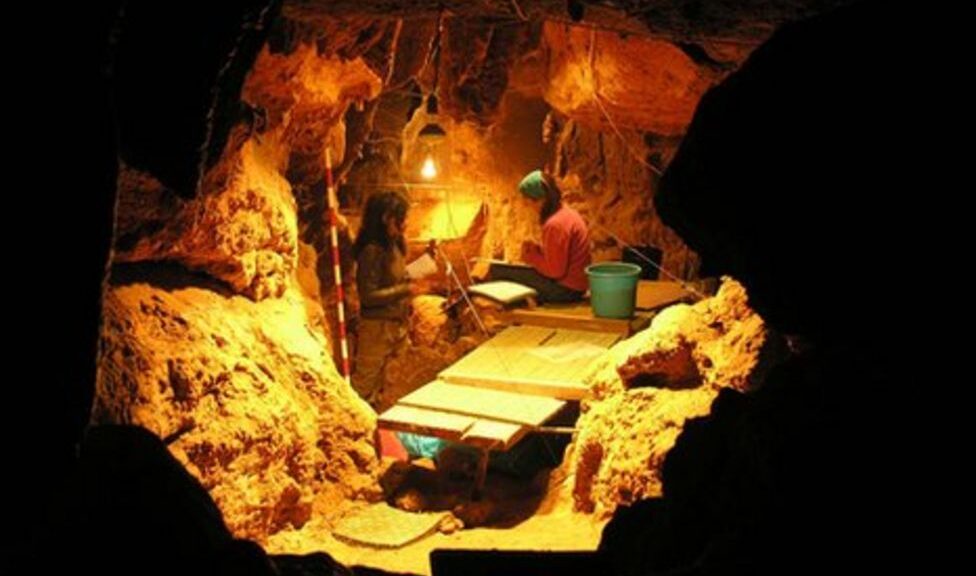

The Monterilio tholos, excavated between 2007 and 2010, is “a great megalithic construction…which extends over 43.75 m in total.” It has been constructed out of large slabs of slate and served as a burial site.

The period in which this site was built was well known for the excavation of metals from the ground, and where there is excavation – there can also be crystals.

In the case of the Monterilio tholos, the people there found a way to shape the quartz crystals into weapons.

However, the spot where these crystals were uncovered is not associated with rock crystal deposits, so it means that these crystals were imported from somewhere else.

The rock crystal source used in creating these weapons has not been pinpointed, but two potential sources have been suggested, “both located several kilometres away from Valencina.”

As the academic paper which focuses on these crystal weapons states, the manufacture of the crystal dagger “must have been based on the accumulation of transmitted empirical knowledge and skill taken from the production of flint dagger blades as well from the know-how of rock-crystal smaller foliaceous bifacial objects, such as Ontiveros and Monterilio arrowheads.”

The exact number of ‘crystal weapons’ found on the site has been estimated to “10 crystal arrowheads, 4 blades and the rock crystal core of the Monterilio tholos.”

Interestingly enough, although the bones of 20 individuals were found in the main chamber, none of the crystal weapons can be ascribed to them.

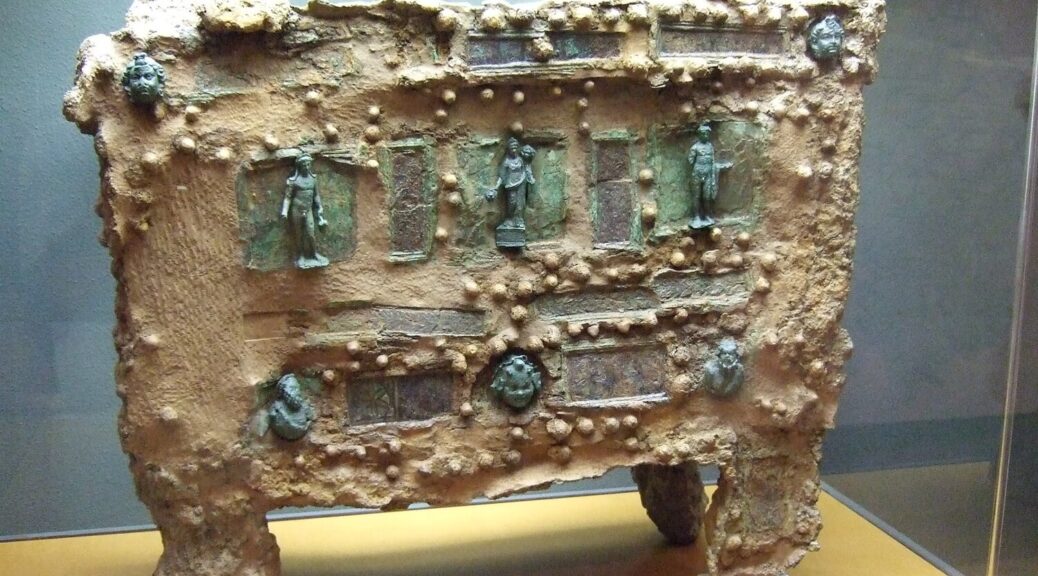

The individuals had been buried with flint daggers, ivory, beads, and other items, but the crystal weapons were kept in separate chambers.

These crystal weapons could have had ritualistic significance and were most probably kept for the elite. Their use was perhaps closely connected to the spiritual significance they possessed. Indeed, many civilizations have found crystals as having a highly spiritual and symbolical significance.

The paper states that “they probably represent funerary paraphernalia only accessible to the elite of this time period.

The association of the dagger blade to a handle made of ivory, also a non-local raw material that must have been of great value, strongly suggests the high-ranking status of the people making use of such objects.”