Skull found in Turkey with neat hole may have been the work of mystics

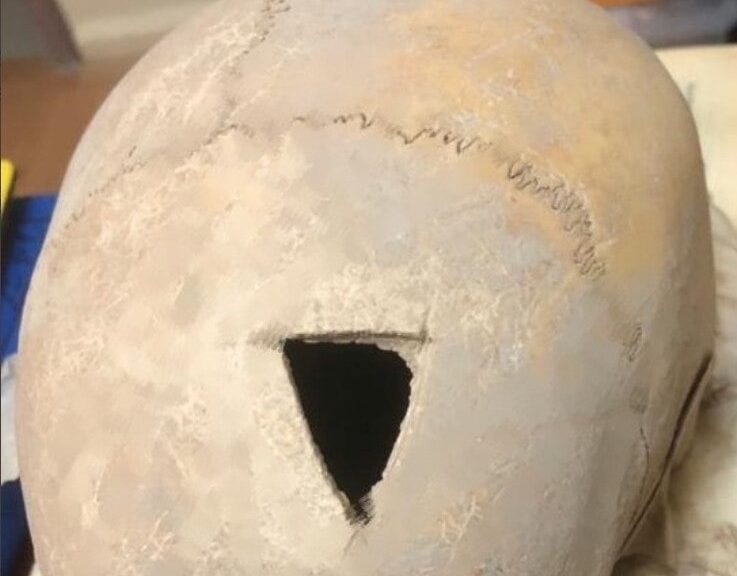

A 3,200-year-old skull was recently uncovered in Turkey’s eastern Van province. This find was made even more intriguing by the skull’s clearly man-made triangle-shaped hole, indicating that the deceased owner had undergone an ancient medical procedure now called trepanation.

Trepanation, a procedure that involves drilling a hole into the patient’s skull, is one of the oldest known surgical procedures in human history and a practice used by ancient humans all over the world. Archaeologists have found trepanned skulls in Europe, the Americas, Africa and China.

Skull-drilling in the 21st century

The practice is still used today to treat subdural hematomas, but surgeons have refined the process and now refer to it as a craniotomy or a burr hole.

Burr holes tend to be used in emergency situations after a traumatic head injury to relieve pressure due to fluid buildup in the skull which puts undue pressure on brain tissue. Craniotomies, per the National Cancer Institute, resemble ancient trepanation more so than burr holes; the surgeon removes a small piece of the skull in order to gain access to the brain.

This is sometimes used to relieve pressure, but can also be used to remove a tumor or a tissue sample, as well as to repair a skull fracture or brain aneurysm (a bulge in a blood vessel wall).

Unlike in ancient trepanation practices, modern surgeons nearly always replace the removed piece of the skull once they have finished their procedure.

What was the practice used for in ancient times?

According to the science news website Live Science, trepanation was used in ancient times to treat head injuries and pain, and some scientists believe it was used to ritually remove evil spirits from the body.

A 2013 article published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology concluded that often, patients did survive the procedure and would heal after surgery. Researchers found scarring from trepanation, but the injury to the skull had healed.

Researchers have not yet determined whether the skull found recently in Turkey belonged to a survivor or a victim of trepanation. They also do not yet know – and perhaps never will find out – whether the procedure was performed in order to treat a medical issue or exorcise demons.