Largest Human Family Tree Identifies Nearly 27 Million Ancestors

A team of scientists has combined modern and ancient genomes to build a new “genealogy of everyone,” in an achievement that sets the groundwork for future studies into our evolution and global spread.

Thousands upon thousands of modern and ancient human genomes have been integrated into a coherent and unified genealogy, according to new research published in Science. It’s akin to a family tree, but it’s a whopper, as it contains nearly 27 million ancestors, making it the largest human genealogy ever created. The new map could be used to study human evolution and even assist with medical research having to do with hereditary diseases.

‘We have basically built a huge family tree, a genealogy for all of humanity that models as exactly as we can the history that generated all the genetic variation we find in humans today,” Yan Wong, an evolutionary geneticist at the Big Data Institute and a co-author of the study, explained in a University of Oxford statement. “This genealogy allows us to see how every person’s genetic sequence relates to every other, along with all the points of the genome.”

The network shows how individuals around the world are related to each other, and it predicts common ancestors, including when they lived and where they came from. It also models key events in human history, such as human migrations out of Africa and dispersals to other parts of the globe.

Researchers have been collecting human genomes for years, but the challenge has been in making sense of it all from a larger, holistic perspective.

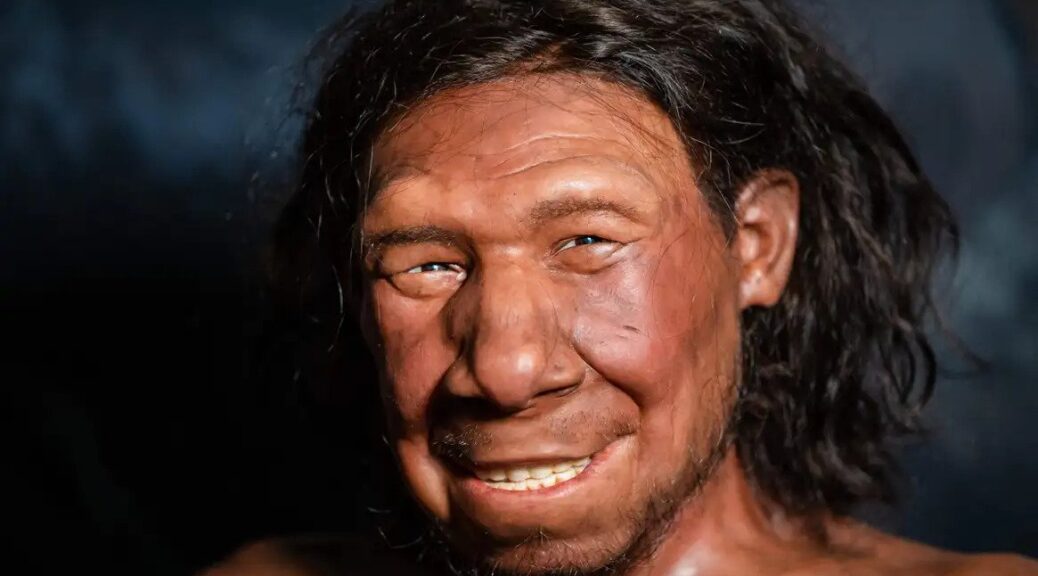

Comparisons of these genomes have been difficult owing to disparate methods of gathering the data, the presence of multiple databases, and variances in terms of data quality and analysis. To compound the problem, each human genome contains segments from multiple ancestries, whether from various ethnic groups or different human populations altogether, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

These ancestries also exist across vast timescales, which represents yet another challenge. What’s needed are algorithms that can accommodate these challenges, and that’s exactly what the researchers are claiming to have achieved.

To create the map, Wong, with his colleagues, applied a “non-parametric tree-recording method” to modern and ancient human genomes, the oldest of which date back hundreds of thousands of years. I reached out to Sharon Browning, a biostatistician at the University of Washington who wasn’t involved in the research, to get her to take on the achievement.

“This paper is primarily about a great new tool for genetic studies called tskit, which is short for ‘tree sequence kit’,” explained Browning in an email. It’s called a tree because, “if you consider one small part of the genome in a number of individuals, and trace back the descent, eventually you get back to a single ancestor, like ‘mitochondrial Eve’ for the mitochondrial genome,” she said.

“That single ancestor is the root of the tree, and the set of individuals that you were considering are the tips of the branches of the tree.” Browning said the tree looks different along with different parts of the genome because of recombination (when the exchanging of genetic material results in variation), and that tskit is “used to infer the trees along the sequenced genome.”

Indeed, the algorithms work by predicting where common ancestors must be present in the evolutionary family tree, by looking at genetic variation. And because the genomes are geotagged, it predicts where these common ancestors lived.

“Essentially, we are reconstructing the genomes of our ancestors and using them to form a vast network of relationships,” Anthony Wilder Wohns, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the Big Data Institute, said in the Oxford release.

“We can then estimate when and where these ancestors lived. The power of our approach is that it makes very few assumptions about the underlying data and can also include both modern and ancient DNA samples.”

Browning said an earlier version of tskit showed promise, but it turned out to have significant limitations. The researchers have now addressed the limitations, “providing a tool that should be extremely useful across many different types of study,” she said. To which she added: “Although the authors provide a couple of applications, including their cool visualization of where human ancestors came from, the scope of possible applications is very large, and I would expect to see a flurry of activity from researchers developing these.”

Browning cautioned that the trees estimated by tskit “don’t come with uncertainty measures,” so she expects the results will be useful for positing new hypotheses, rather than for proving hypotheses. “Other more specialized methods will still be needed for verification purposes,” she said.

Looking ahead, the team hopes to add new genetic information to the system as it arrives. They don’t expect this to be a problem, as the system can accommodate millions more.