Egypt breakthrough: How 2,000-year-old mystery was solved after ‘lost labyrinth’ discovery

The discovery was made in Dahshur, an archaeological site 90km south of Cairo, where the tattered remains of Pharaoh Amenemhat III’s Black Pyramid can be seen today. The huge mortuary temple that originally stood adjacent to this pyramid is believed to have formed the basis of the complex of buildings with galleries and courtyards called a “labyrinth” by famed ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

With no visible remains, the story was thought to simply be a legend passed down by generations until Egyptologist Flinders Petrie uncovered its “foundations” in the 1800s, leading experts to theories the labyrinth was demolished under the reign of Ptolemy II and used to build the nearby city of Shedyt to honour his wife Arsinoe. But, in 2008, archaeologists working on the Mataha Expedition made a stunning find below the sands, researcher Ben Van Kerkwyk revealed on his YouTube channel ‘UnchartedX’ earlier this year.

He said in January: “It is a rare thing for ancient historical mysteries to ever be fully resolved.

“Great enigmas like the pyramids of Egypt seem to somehow resist the passage of time, unchanging as it flows around them like boulders in the river of history.

“Occasionally our civilisation makes some small incremental progress, a new tomb is found or some object discovered destined to become yet another piece in a museum.

“12 years ago, in 2008, a momentous discovery was made beneath the sands of Egypt, this wasn’t some small incremental step, but represented rather a huge leap forward – an opportunity for historical exploration and learning – the likes of which we have not witnessed in a century.

“The great lost labyrinth of ancient Egypt had been found.”

Mr Van Kerkwyk went on to detail what the area may have looked like some 2,000 years ago.

He added: “This was a gigantic and mythical structure, said by some to have surpassed the achievements of the pyramids, a huge array of thousands of underground halls, temples and chambers, dwarfing all known Egyptian temple sites several times over.

“This structure was visited and witnessed first-hand by the great historians of millennia past, yet ultimately, was lost to the sands of the desert and its physical presence remained unknown for more than 2,000 years.

“Unknown until 12 years ago, the discovery was suppressed and today the incredible potential of this site is being slowly and irrevocably destroyed by both inaction by authorities and by the water table in the area that’s rising.

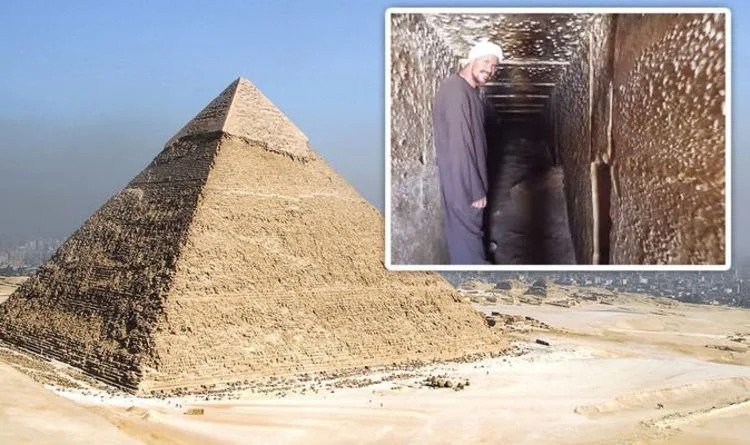

“Compared with Giza or any of the other well-known ancient Egyptian sites, there really isn’t a lot to immediately take in.”

Mr Van Kerkwyk detailed how Mr Petrie first stumbled across the find.

He added: “Some fragments of once-mighty granite columns carved in palm or lotus shapes along with other small fragments of ancient stonework are left lying in a small, open-air museum.

“The site is dominated by the remains of the pyramid of Amenemhat III with only the mud-brick internal structure remaining to see.

“The remains of the labyrinth have been discovered in the sandy areas to the south of the pyramid.

“The first to find any real evidence of this was the great Flinders Petrie, who, in the late 1800s, discovered the remains of a huge stone foundation, more than 300 metres broad around four metres beneath the sand.

“He concluded that this was the remnants of the foundations for the labyrinth, with the structure itself being long since quarried and destroyed.”

Archaeologists found evidence of a huge structure hiding below the sand in 2008, but Mr Van Kerkwyk said the area has never been excavated.

He continued: “However, new evidence collected in modern times is challenging his conclusion and it now seems likely that what Petrie found was not the foundation, but instead was part of the ceiling or roof.

“These same areas were scanned in 2008, using ground-penetrating radar, by the Mataha Expedition, a collaboration between Egyptian authorities, the Ghent University of Belgium and funded by contemporary artist Louis De Cordier.

“The results of this expedition clearly indicate the presence of grid-like and ordered structures deep beneath the sand in levels much deeper than Petrie ever excavated.

“Although this expedition was conducted with the full cooperation and permission of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the official results and conclusion of this legitimate scientific study have never been released.”