El-Kurru’s Carved Graffiti Reveal Another Side of Ancient Nubia

Now, northern Sudan, which has mostly desert boundaries with Egypt. Moreover, this part of the Nile Valley was once the domain of Kush, a strong African civilization. It traded in Egypt and in the Mediterranean region gold and the products of inner Africa.

For over 2000 years Kush has been the largest power in this region, reaching its greatest extent in conquering Egypt as its 25th dynasty from about 725-653 BCE. Kush was ruled from the capital of Meroe in the years 300 BCE to 300 CE.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, the city was built on the Nile about 100 miles north of modern-day Khartoum, Sudan’s capital.

Other regions of Kush remained important, however. These included the older capital region of Napata, which centered on the “holy mountain” of Jebel Barkal and included the nearby pyramid cemetery of El-Kurru.

There were a number of temples and other sacred sites in Kush. And, as per the research in El-Kurru has documented, visitors to these sites had one particular religious ritual that may strike some as strange: they carved graffiti in important and sacred places.

These graffiti can still be seen today at several sacred sites in what was the kingdom of Kush – on a pyramid and in a temple at El-Kurru, at a seasonal pilgrimage center called Musawwarat es-Sufra, and in the Temple of Isis at Philae, at the border with Egypt.

The curators of an exhibition detailing the recently discovered graffiti from El-Kurru.

The exhibition is on view at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan until March 2020. It features photographs, text, and interactive media presentations that unpack the practice and its importance in Kushite society.

A catalog written in conjunction with the exhibition presents selected examples of graffiti from the Nile valley and beyond, including the ancient Roman city of Pompeii.

All accustomed to understanding ancient cultures almost entirely through the activities of the powerful elite and the art they left behind in their palaces, temples, and tombs. But that creates a distorted picture of ancient life – as distorted as such a picture would be today.

The graffiti featured in this exhibition allows a glimpse into some of the activities of non-elite people and their religious devotion to particular places. It’s a reminder that society is more than the elite and powerful.

Marking place and time

The graffiti at El-Kurru were discovered by a Kelsey Museum archaeological excavation, on a pyramid, and in an underground temple at the site.

El-Kurru was a royal cemetery for the kings of the Napatan dynasty, who ruled Egypt as the 25th dynasty. But the graffiti date to several hundred years after the kings’ rule. By this time the pyramids and funerary temple were partially abandoned, yet people were visiting the site and carving graffiti.

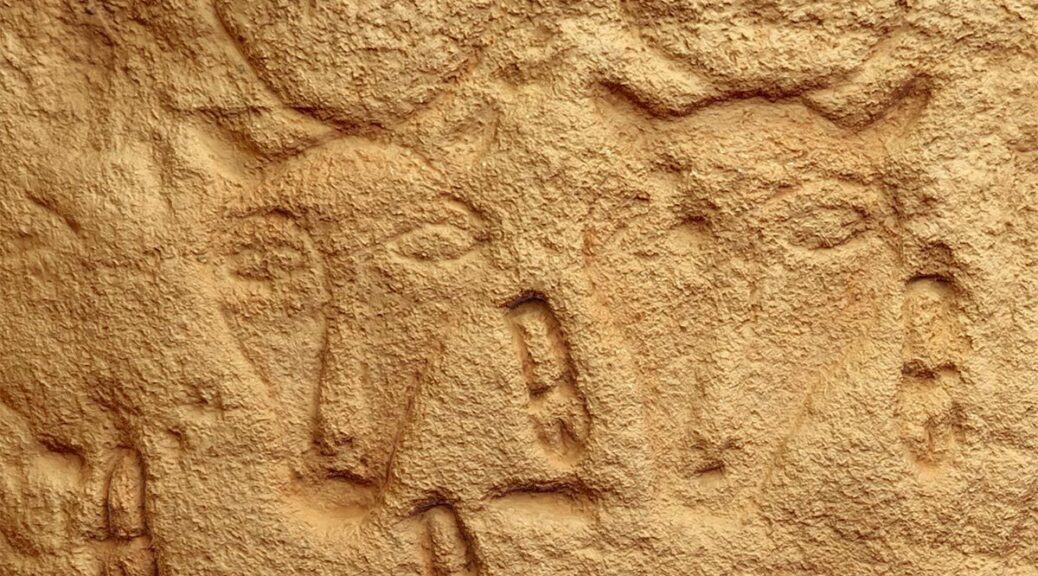

The graffiti includes clear symbols of ancient Kush, like the ram that represented the local form of the god Amun, and a long-legged archer who symbolized Kushite prowess in archery. There are also intricate textile designs as well as animals – beautiful horses, birds, and giraffes.

The most common marks are small round holes gouged in the stone. By analogy with modern practices, these are probably areas where temple visitors scraped the wall of the holy place to collect powdered stone that they would ingest to promote fertility and healing.