Indigenous artifacts found near Ottawa give clues to a settlement dating back 10,000 years

Archeologists have uncovered a cache of artifacts near Ottawa that could shed new light on trade and communication networks between Indigenous communities thousands of years ago.

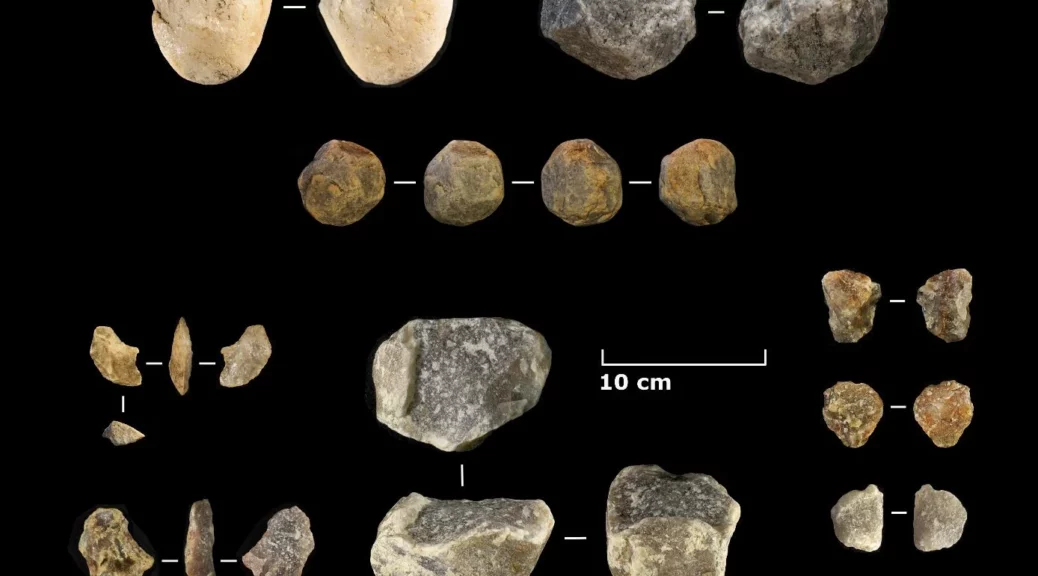

The discovery last month in Lac Philippe, Que., included about 50 pieces of rare quartz tools, which suggest that Indigenous peoples may have inhabited the area up to 10,000 years ago.

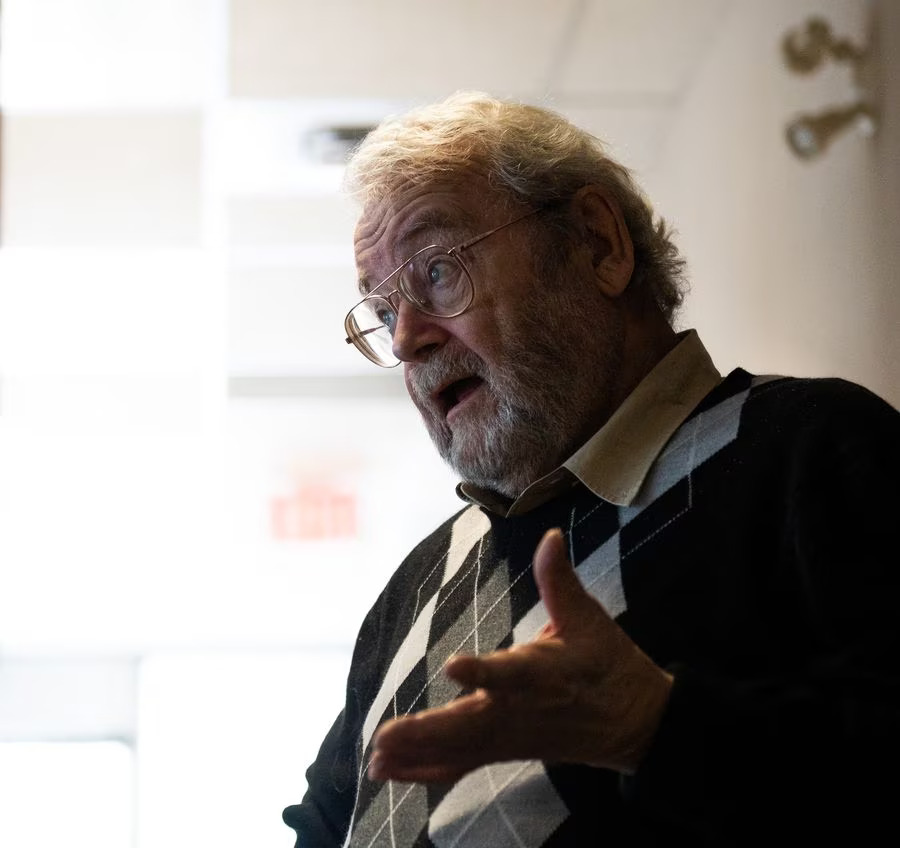

Head archeologist Ian Badgley and his team from the National Capital Commission found the artifacts within hours of starting the dig at the ancient Indigenous settlement. It was the first time they’d found quartz tools in the area.

Mr. Badgley had originally thought the settlement dated back about 3,000 years.

“We think the quartz could be as old as 10,000 years. It’s an eye-opener,” said Mr. Badgley, manager of the NCC’s archeology program, who has been excavating Indigenous sites in Canada for 50 years.

This is not the first significant discovery in the area. Earlier this year, The Globe and Mail reported that hundreds of thousands of precontact Indigenous artifacts found near Ottawa were being stored in boxes in an office suite in an NCC building steps from Parliament.

Many of the Indigenous tools were shaped from chert quarried millennia ago, including a knife found on Parliament Hill estimated to be about 4,000 years old. Doug Odjick, a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg council, said Indigenous artifacts from the area help to educate others about the history of his ancestors.

“We’d like to show people that there was life before Champlain arrived,” he said. “There was civilization. There was trade. There were different methods of gathering.”

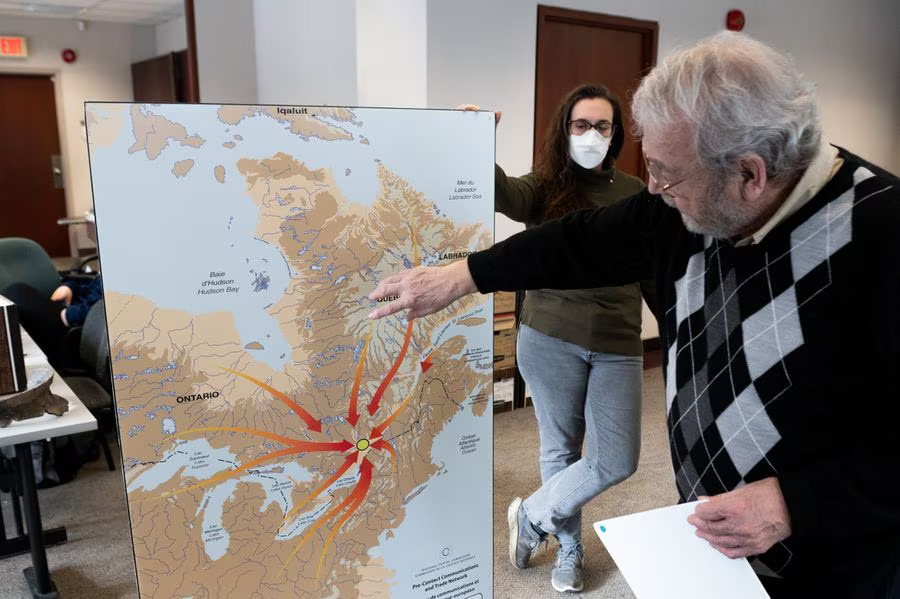

The National Capital Region where the quartz materials were found is “at the hub of a vast precontact communications and trade network,” Mr. Badgley said.

It is situated at the confluence of three major river systems, which acted as major transportation and trade routes. The Kitigan Zibi traded here with other Indigenous peoples such as the Mohawk and Huron.

When Indigenous communities traded, they exchanged more than material items, Mr. Odjick said. “Part of the deal was the trade of knowledge.”

Chief Simon John, from the Ehattesaht Tribe on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island, said a lot of this traditional knowledge has been lost. Many Indigenous peoples rely on oral history to pass down stories, traditions, and culture. While the discovery of Indigenous artifacts may validate relationships between communities, he added, they don’t tell the whole story. Indigenous students from the Anishinabe Odjibikan federally funded archeological field school are taking part in the next stage of excavations this week, and are excited to discover what the finds can tell them about their ancestors.

The students are from the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, located north of Gatineau, and the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan, about 150 kilometers southwest of Ottawa. Jenna Kohoko is one of the students from Pikwakanagan First Nation. While the group was not a part of the initial Lac Philippe digs, they helped clean the first batch of quartz.

“I love looking at the quartz artifacts,” Ms. Kohoko said. “It really says to me that we were here so long ago, we occupy the space, and we were here a lot earlier than people assume.”

Archeologists have also uncovered quartz materials in Pikwakanagan, more than 100 kilometers away from Gatineau Park. Mr. Badgley said the team will be comparing the quartz from these two sites; the new materials are currently being radiocarbon dated in a lab at the University of Ottawa.

They are eagerly awaiting the results, which will take around three months to come in.

“This will tell us more about who these people are, who they were related to, where they were living, and how they moved around,” he said. “It’s exciting.”