7,000-Year-Old Unique Artifacts Discovered Under Melting Ice In Canada

Archaeologists have discovered dozens of unique artifacts that span more than 7,000 years in melting ice patches in British Columbia’s Mount Edziza Provincial Park, Canada.

During the survey, over 50 perishable artifacts were found near Goat Mountain and the Kitsu Plateau in Mount Edziza Provincial Park, a region that is a volcanic landscape “extremely significant” to the Tahltan, one of Canada’s indigenous First Nations.

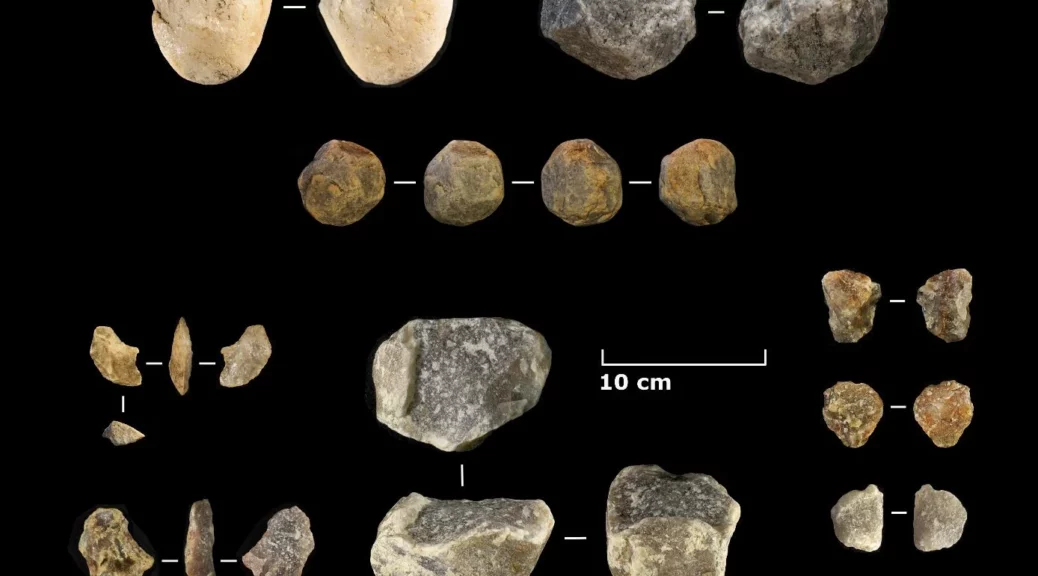

The finds include stitched birch bark containers, wooden walking staffs, carved and beveled sticks, an atlatl dart foreshaft, and a stitched hide boot, the research team writes in their study published in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

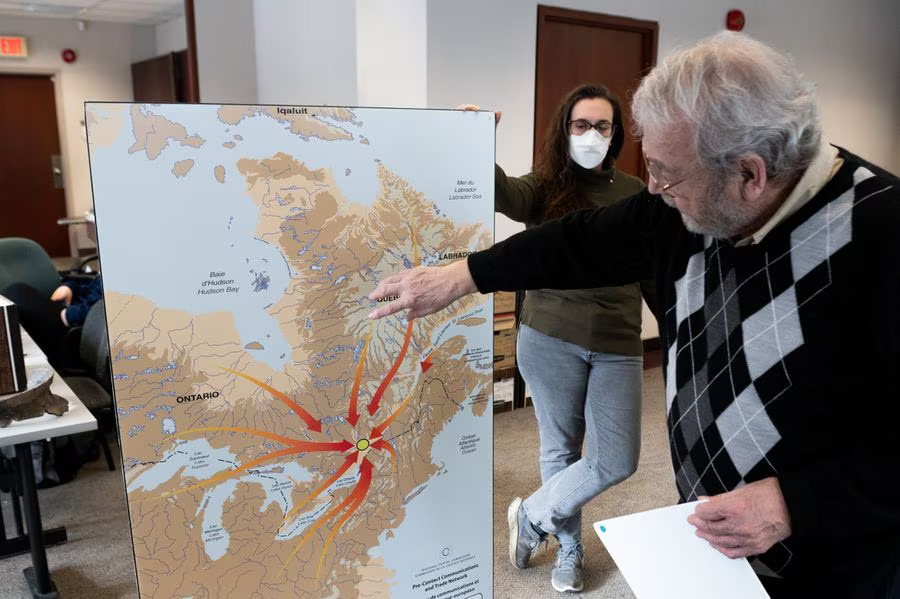

While previously exploring the area, scientists discovered many “vast obsidian quarries” and obsidian artifacts in the park.

However, the nearby ice patches had not been examined as extensively. This time, scientists wanted to find out if perishable ancient artifacts were preserved in the ice.

The study of nine ice patches led to the discovery of 56 perishable artifacts.

“Most of the perishable artifacts were manufactured from wood, including birch bark containers, projectile shafts, and walking staffs,” researchers said. Other artifacts were made “using animal remains include a stitched hide boot and carved antler and bone tools.”

According to a report in the Miami Herald, “Archaeologists found two bark containers with stitching.” One of these is a” 2,000-year-old piece of bark is folded with two rows of stitching along one side and some of the stitching material still left in the holes, the study said.

The other “unique” bark container has sticks stitched into its sides, suggesting it was part of a reinforced basket used for transporting heavy loads. Researchers said it dates back over 1,400 years.”

“Archaeologists also uncovered an artifact made of stitched animal hide that they identified as the remains of a moccasin-like boot,” which is about 6,200 years old. It has “two different thicknesses of hide … which have been stitched in multiple places,” the study said.

Another intriguing object uncovered under the ice was a 5,300-year-old antler shaped like an ice pick. The research team explained the three-pronged antler had one sharpened point, one blunted as if used as a hammer, and one broken but presumed to be used as a handle.

“Every perishable artifact was found amongst a backdrop of millions of obsidian” artifacts, the study said. The artifacts were taken to a museum in British Columbia for “climate-controlled conservation” and further study.

“Radiocarbon ages on 13 of the perishable artifacts reveal that they span the last 7000 years,” the study informs.