Laser mapping reveals the oldest Amazonian cities, built 2500 years ago

Archaeologists once believed the ancient Amazon rainforest was an inhospitable place, sparsely populated by bands of hunter-gatherers. But the remains of enormous earthworks, pyramids, and roads from Bolivia to Brazil discovered over the past two decades have proved conclusively that the Amazon was home to large, complex societies long before European colonizers arrived. Now, there’s evidence that another human society—the oldest yet—left its mark on the region: A dense network of interconnected cities, now hidden beneath the forest in Ecuador’s Upano Valley, has been revealed by the laser mapping technology called lidar.

The settlements, described today in Science, are at least 2500 years old, more than 1000 years older than any other known complex Amazonian society.

Lidar, which allows researchers to see through forest cover and reconstruct the ancient sites below, “is revolutionizing our understanding of the Amazon in pre-Columbian times,” says Carla Jaimes Betancourt, an archaeologist at the University of Bonn who wasn’t involved in the new work.

Finding such an ancient urban network in the Upano Valley highlights the long-unrecognized diversity of ancient Amazonian cultures, which archaeologists are just beginning to be able to reconstruct.

Stéphen Rostain, an archaeologist at CNRS, France’s national research agency, began excavating in the Upano Valley nearly 30 years ago. His team focused on two large settlements, called Sangay and Kilamope, and found mounds organized around central plazas, pottery decorated with paint and incised lines, and large jugs holding the remains of the traditional maize beer chicha.

Radiocarbon dates showed the Upano sites were occupied from around 500 B.C.E. to between 300 C.E. and 600 C.E. “I knew that we had a lot of mounds, a lot of structures,” Rostain says. “But I didn’t have a complete overview of the region.”

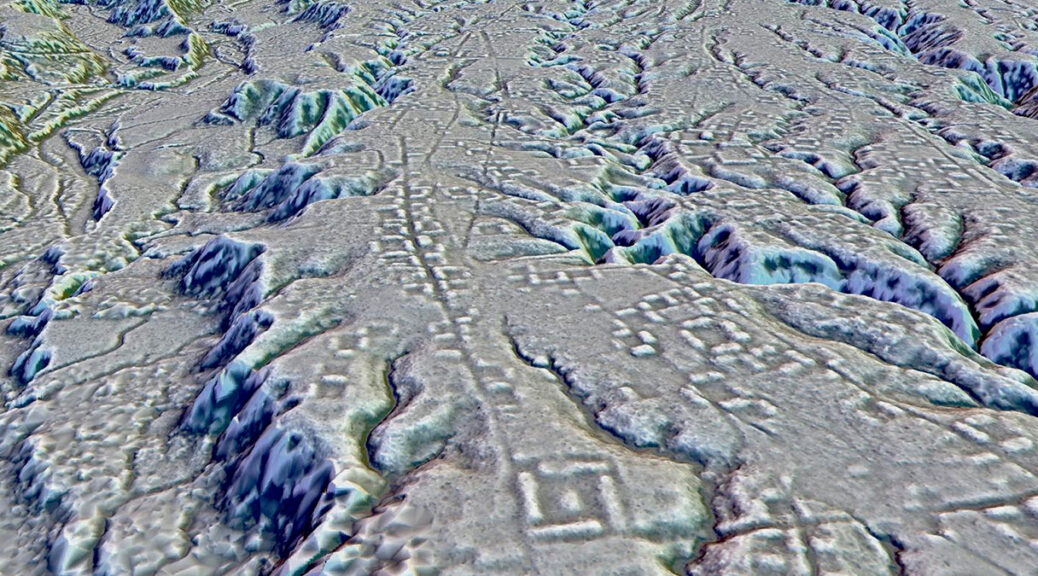

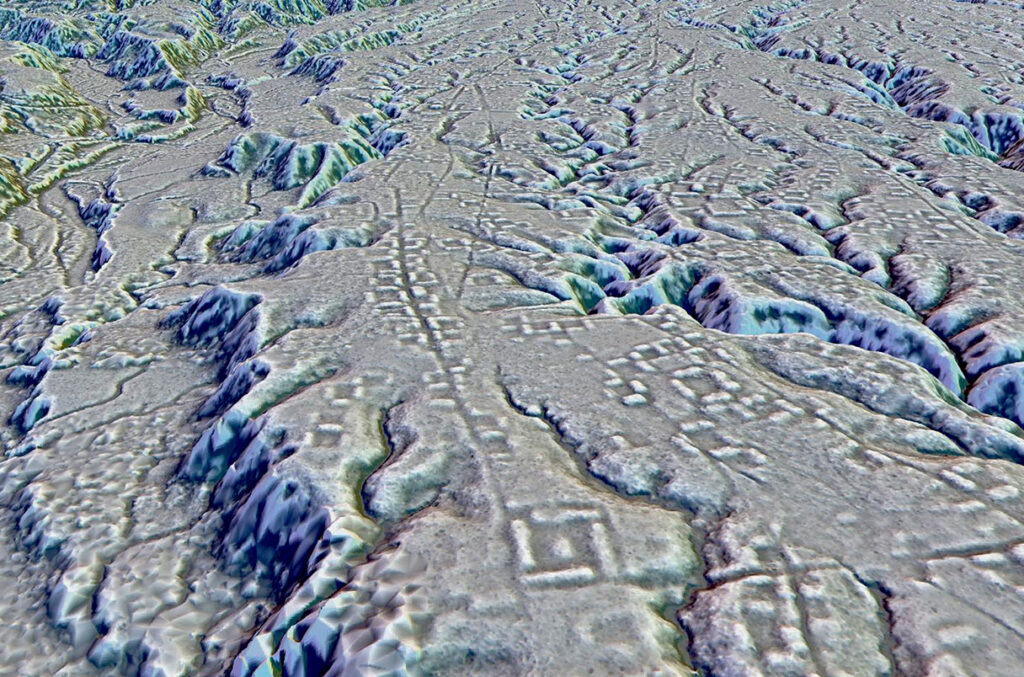

That changed when Ecuador’s National Institute for Cultural Heritage funded a lidar survey of the valley in 2015. Specially equipped planes beamed laser pulses into the forest and measured their return path, revealing topographic features otherwise invisible under the trees.

The lidar data allowed Rostain and his collaborators to see the connections between settlements and also uncovered many more. “Each day it was Christmas, with a new gift,” Rostain says. The team identified five large settlements and 10 smaller ones across 300 square kilometers in the Upano Valley, each densely packed with residential and ceremonial structures.

The cities are interspersed with rectangular agricultural fields and surrounded by hillside terraces where people planted crops, including the corn, manioc, and sweet potato found in past excavations. Wide, straight roads connected the cities to one another, and streets ran between houses and neighborhoods within each settlement. “We’re talking about urbanism,” says co-author Fernando Mejía, an archaeologist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

Although the researchers don’t yet know how many people lived in the Upano Valley, the settlements were large: The core area of Kilamope, for example, covers an area comparable in size to the pyramid-studded Giza Plateau in Egypt or the main avenue of Teotihuacan in Mexico.

The extent of Upano’s landscape modification rivals the “garden cities” of the Classic Maya, the authors say. And what’s been discovered so far “is just the tip of the iceberg” of what could be found in the Ecuadorian Amazon, Mejía says.

The network of roads connecting the Upano sites suggests they all existed at the same time. They are a millennium older than other complex Amazonian societies, including Llanos de Mojos, a recently discovered ancient urban system in Bolivia.

The Upano Valley cities were denser and more interconnected than sites in Llanos de Mojos, Rostain says. “We say ‘Amazonia,’ but we should say ‘Amazonias,’” to capture the region’s ancient cultural diversity, he says.

The details of each culture, however, are still coming into view. People in both the Upano Valley and Llanos de Mojos were farmers who built roads, canals, and large civic or ceremonial buildings. But, “We’re just beginning to understand how these cities were functioning,” including how many people lived in them, who they traded with, and how they were governed, says Jaimes Betancourt, who studies Llanos de Mojos.

So it’s too soon to compare the Upano cities with societies such as the Classic Maya and Teotihuacan, which were “much more complex and more extensive,” says Thomas Garrison, an archaeologist and geographer at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in lidar and wasn’t involved in the work. Still, he says, “It’s amazing that we can still make these kinds of discoveries on our planet and find new complex cultures in the 21st century.”