One of Scotland’s great mysteries: the 5,200 years old carved stone balls

Scottish carved stone balls are a mysterious class of artefacts, and scientists have been the subject of much speculation by scientists over the years.

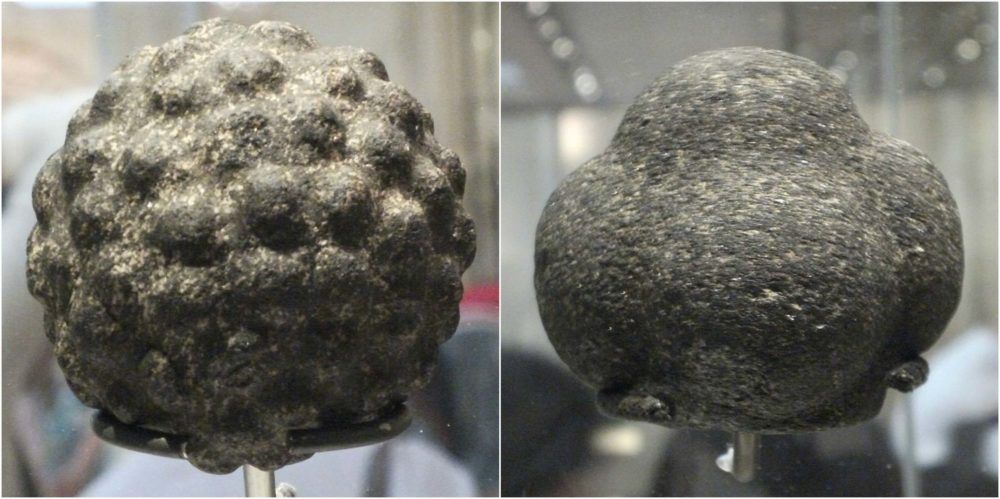

In all, more than 500 stone balls were collected, the largest to fit neatly into the palm of the hand. They were designed so that a number of knobs protrude from the surface and some have beautiful, intricate patterns incised onto them.

So elaborate are the carvings that early archaeologists didn’t believe it was possible for them to have been made using flint tools, so they dated them to a later period. But we know they were indeed carved using flint and date back to around 3,200 BC to 2,500 BC, a time when people in Scotland were leaving their lives as hunter-gatherers and settling into life in farming communities.

What were they for?

Although no hard evidence exists to definitively determine their function, many have speculated as to the stones’ purpose.

Some believe that they were part of a weighing system for primitive scales, but others argue that their weights vary too much for that to be practical. They might have been used to weigh down fishing nets, or as bearings to move bigger rocks, but then why would they be carved so elaborately?

Australian author Lynne Kelly has proposed that the stone balls served as “memory devices” that could have been used as mnemonic aids to the oral history of the times, much like Australian Aboriginal cultures used rock art and their surroundings.

Others have suggested they were used as weapons — either fixed to a wooden handle or simply thrown. But most of the stones show no signs of the kind of damage you’d expect to see on a weapon.

“It is perhaps best to think of them as ceremonial or stylized weapons,” explains Hugo Anderson-Whymark, curator of National Museums Scotland. “Things that could inflict damage if you wanted to use them, and may in some circumstances have been used that way, but are more likely to be objects which represent the status or power of the individual that held them in that community.”

Prehistoric stone balls in 3D

In an effort to gain more understanding, and make the stones more accessible to the public, Anderson-Whymark has created 3D images of the balls. Using a technique called photogrammetry, Anderson-Whymark took hundreds of 2D images from every angle to create very detailed 3D renderings of 60 carved stone balls.

The images, which have been uploaded online for anyone to see, revealed details of the stone balls that had not previously been visible.

“Actually being able to see them in virtual reality is hugely valuable,” Anderson-Whymark told CNN. “It allows us to see some fine details which we didn’t spot before.

“There’s one of them that has concentric lines on the circles, and no one had ever seen that before and it’s been in our collection for well over 100 years,” he added.

The 3D images also revealed that some of the stones were modified over time, possibly across generations. It’s still unclear what that could mean, but Anderson-Whymark said that at the very least it opens the door to other possibilities about the balls’ purpose and significance to people of that era.

“It’s telling us how they were worked and re-worked over time. It’s allowing us to explore that bigger story of how they were made and how they developed, which is potentially going to tell us more about that bigger theory of how they were used,” Anderson-Whymark said.

While a few of the balls have been found in Ireland and northern England (one even travelled to Norway), all the others have been found in Scotland, mostly in Aberdeenshire. Five were found at the remarkably preserved Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae, in the Orkney Islands, off the northern coast of Scotland.

National Museums Scotland, in Edinburgh, has the world’s largest collection of these carved stone balls at around 200 (including 60 casts). Perhaps most famous among them is the Towie ball. Found in Aberdeenshire in the 19th century, it features neatly carved circles, spirals and lines on four knobs.

“The Towie carved stone ball is the finest example of a carved stone ball from Scotland and the motifs on it are just absolutely incredible,” Anderson-Whymark said. “The very fine grooves on the surface are about a millimetre across and have all been carved with a flint tool. Incredibly fine, delicate workmanship.”

An enduring enigma

According to the museum, the patterns on the Towie ball are sacred symbols resembling those in a passage grave in Ireland. Anderson-Whymark says the similarities in the design raise interesting questions about the relationships between these locations.

“One thing they show is that there was perhaps a long-distance contact in that period which we don’t always give prehistoric people credit for,” he said.

“Certainly, when we look at Orkney, we see objects which are moving up from around the west coast through the western seaways … The grooved ware (a style of British Neolithic pottery) originates in Orkney and it travels south towards Ireland and into southern Britain as well.

“We’re seeing things, ideas and people moving with them through that time.”

The enigma of the stone balls will endure for now, and while we may never know exactly what they were used for, we can still appreciate them as fine examples of Neolithic art.