Vikings Weren’t All Scandinavian, Ancient DNA Study Shows

The term “Viking” tends to conjure up images of fierce, blonde men who donned horned helmets and sailed the seas in longboats, earning a fearsome reputation through their violent conquests and plunder.

But a new study published in the journal Nature suggests the people known as Vikings didn’t exactly fit these modern stereotypes. Instead, a survey deemed the “world’s largest-ever DNA sequencing of Viking skeletons” reinforces what historians and archaeologists have long speculated: that Vikings’ expansion to lands outside of their native Scandinavia diversified their genetic backgrounds, creating a community not necessarily unified by shared DNA.

As Erin Blakemore reports for National Geographic, an international team of researchers drew on remains unearthed at more than 80 sites across northern Europe, Italy and Greenland to map the genomes of 442 humans buried between roughly 2400 B.C. and 1600 A.D.

The results showed that Viking identity didn’t always equate to Scandinavian ancestry. Just before the Viking Age (around 750 to 1050 A.D.), for instance, people from Southern and Eastern Europe migrated to what is now Denmark, introducing DNA more commonly associated with the Anatolia region. In other words, writes Kiona N. Smith for Ars Technica, Viking-era residents of Denmark and Sweden shared more ancestry with ancient Anatolians than their immediate Scandinavian predecessors did.

Other individuals included in the study exhibited both Sami and European ancestry, according to the New York Times’ James Gorman. Previously, researchers had thought the Sami, a group of reindeer herders with Asiatic roots, were hostile toward Scandinavians.

“These identities aren’t genetic or ethnic, they’re social,” Cat Jarman, an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo who wasn’t involved in the new research, tells Science magazine’s, Andrew Curry. “To have a backup for that from DNA is powerful.”

Overall, the scientists found that people who lived in Scandinavia exhibited high levels of non-Scandinavian ancestry, pointing to a continuous exchange of genetic information across the broader European continent.

In addition to comparing samples collected at different archaeological sites, the team drew comparisons between historical humans and present-day Danish people.

They found that Viking Age individuals had a higher frequency of genes linked to dark-coloured hair, subverting the image of the typical light-haired Viking.

“It’s pretty clear from the genetic analysis that Vikings are not a homogenous group of people,” lead author Eske Willerslev, director of the University of Copenhagen’s Center of Excellence GeoGenetics, tells National Geographic. “A lot of the Vikings are mixed individuals.”

He adds, “We even see people buried in Scotland with Viking swords and equipment that are genetically not Scandinavian at all.”

The ongoing exchange of goods, people and ideas encouraged Vikings to interact with populations across Europe—a trend evidenced by the new survey, which found relatively homogenous genetic information in Scandinavian locations like mid-Norway and Jutland but high amounts of genetic heterogeneity in trade hubs such as the Swedish islands of Gotland and Öland.

Per the Times, the researchers report that Vikings genetically similar to modern Danes and Norwegians tended to head west on their travels, while those more closely linked to modern Swedes preferred to journey eastward. Still, exceptions to this pattern exist: As Ars Technica notes, Willerslev and his colleagues identified an individual with Danish ancestry in Russia and a group of unlucky Norwegians executed in England.

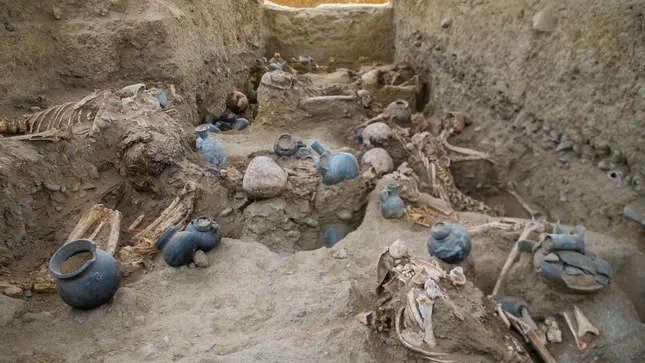

The study also shed light on the nature of Viking raids. In one Estonian burial, the team found four brothers who’d died on the same day and were interred alongside another relative—perhaps an uncle, reports the Times. Two sets of second-degree kin buried in a Danish Viking cemetery and a site in Oxford, England, further support the idea that Viking Age individuals (including families) travelled extensively, according to National Geographic.

“These findings have important implications for social life in the Viking world, but we would’ve remained ignorant of them without ancient DNA,” says co-author Mark Collard, an archaeologist at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, in a statement. “They really underscore the power of the approach for understanding history.”