More evidence shows Vikings came to North America before Columbus

Although the discovery of North America is synonymous with Christopher Columbus, new research reveals that Viking sailors landed on the shores of North America about 700 years before Columbus.

Archaeologists from the University of Iceland came to this conclusion after analyzing wood recovered from five Norse farmsteads in Greenland, according to a study recently published in the journal Antiquity.

Microscopic analysis of wood suggests that Norse people in Greenland were using timber that came from North America over 700 years ago.

The study focused on the timber used in Norse sites in Greenland between 1000 and 1400. According to the findings, some of the wood came from trees grown outside of Greenland.

As part of the study, 8,552 pieces of wood were examined to determine their origin. Only 26 pieces, or 0.27 percent of the total assemblage, belonged to trees that were definitively imported. These were oak, hemlock, beech, and Jack pine.

“These findings highlight the fact that Norse Greenlanders had the means, knowledge, and appropriate vessels to cross the Davis Strait to the east coast of North America, at least up until the 14th century,” archaeologist Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir from the University of Iceland says.

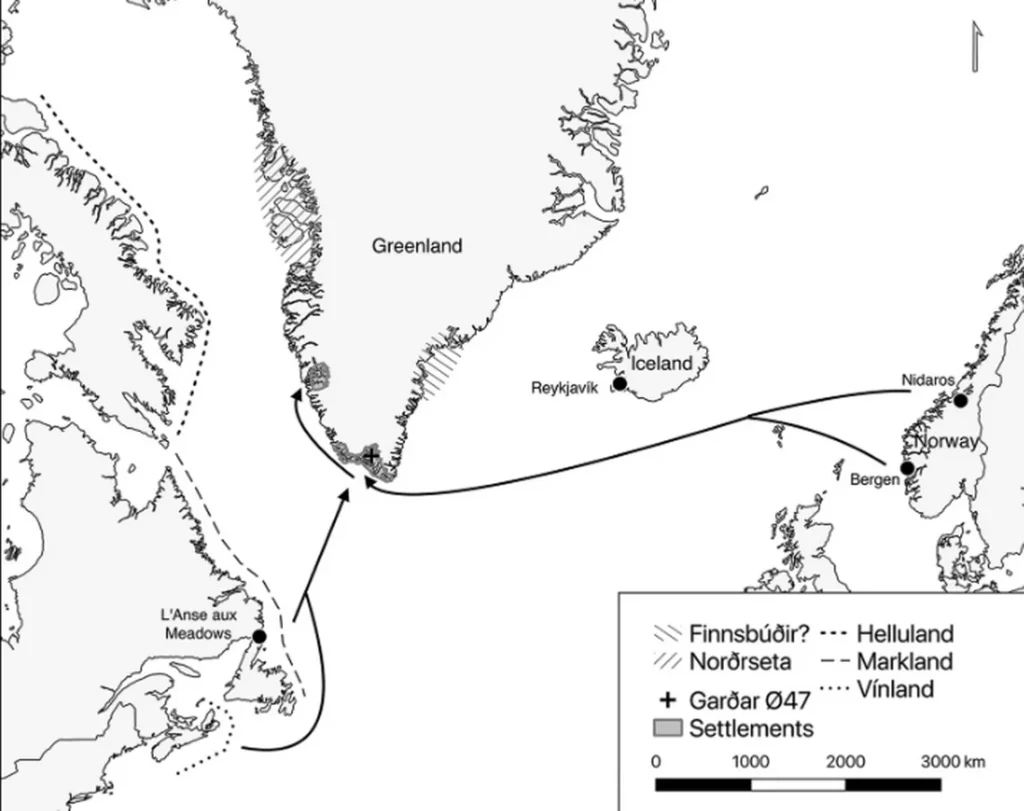

“The wood taxa identified in this study show, without doubt, that the Norse harvested timber resources in North America,” researchers said, adding that the trees could have been felled near the Gulf of St. Lawrence in far eastern Canada.

The few pieces of American wood were only found at one farm known as Garðar, the most prominent of the group.

“This suggests that high-status farms such as Garðar were probably the only settlements that had both the need and the means to acquire North American timber,” researchers said.

Historical records have long suggested that medieval Norse Greenlandic society (985-1450 CE) imported timber from the Americas, but this is some of the first scientific evidence to support the claim.

According to a new study on timber, these epic journeys may have been undertaken in order to hunt for resources.

According to a 13th-century Norwegian text called Konungsskuggsjá, “everything that is needed to improve the land must be purchased abroad, both iron and all the timber used in building houses.”

Grænlendinga saga and Eiríks saga rauða, describe journeys between Greenland to the North American east coast as early as 1000 CE.

There is sturdy evidence to back up this idea. Texts from 14th-century Italy speak of Norsemen making direct contact with a place called Markland, thought to be part of the Labrador coast in Canada.

As for hard evidence of Norse settlements in North America, archeologists in the 1960s excavated a Viking village on the island of Newfoundland that dates to approximately 1,000 years ago. Known as the L’Anse aux Meadows, it’s widely considered to be the earliest evidence of European presence in North America.

According to researchers, the study’s results appear to support claims made in medieval texts that wood was brought from the New World to Europe.