Remains of twin fetuses and wealthy mom found in Bronze Age urn

During the Bronze Age, a pregnant woman carrying twins in what is now Hungary met a tragic end, dying either just before or during childbirth, according to a new study about her burial.

The woman and her twins were cremated and buried in an urn with lavish grave goods: a bronze neck ring, a gold hair ring and bone pins or needles, indicating that the woman was an elite individual, the researchers said. Moreover, a chemical analysis of the woman’s teeth and bones revealed that she wasn’t local but had travelled from afar, likely to marry into a new community, the researchers said.

“Although the external appearance of the urn is not so different from all the others, the prestige objects indicate that the woman stood at the apex of the community or as part of an emerging elite,” study lead researcher Claudio Cavazzuti, an assistant professor in the Department of History and Cultures at the University of Bologna in Italy, told Live Science in an email.

Archaeologists found the woman and twins’ remains in a cemetery dating to the Hungarian Bronze Age (2150 B.C. to 1500 B.C.), which they uncovered during a rescue excavation ahead of the construction of a major supermarket by the Danube River, just a few miles south of Budapest. With 525 burials excavated so far, “the cemetery is one of the largest known in present-day Hungary for this period,” Cavazzuti said. There are likely several thousand more Bronze Age graves in the area that have yet to be excavated, he added.

These burials are from the Vatya culture, which thrived during the Hungarian Early and Middle Bronze Ages, from about 2200 B.C. to 1450 B.C., he said.

The Vatya people had a complex culture, with settlements supporting agricultural farming and livestock, and economy invested in local and long-distance trade (which explains how the Vatya acquired bronze, gold and amber from different parts of Central, Eastern and Northern Europe), and fortifications that controlled parts of the Danube River, Cavazzuti said.

To learn more about those buried in the cemetery, Cavazzuti and his colleagues did an in-depth analysis on 29 burials (26 urn cremations and three were buried). Except for the elite woman (who was buried with the twins), all of the sampled graves contained the remains of just one person, and most of those graves held simple grave goods made of ceramic or bronze.

About 20% of the Vatya burials at the site contained metal grave goods, “but prestige items, such as those of [the elite woman], are rare,” he said.

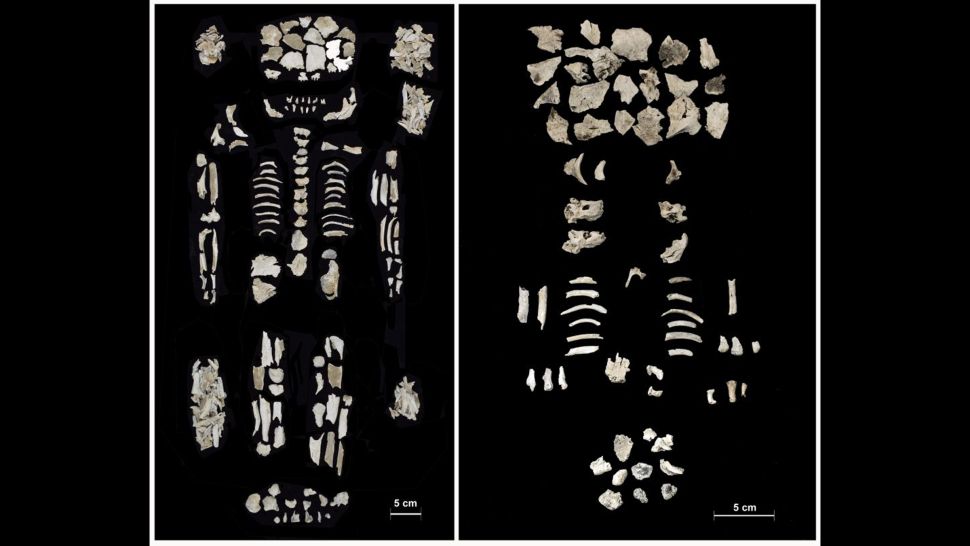

The three buried individuals were adults of indeterminate sex. Of the cremated individuals, 20 were adults (11 females, seven males, two undetermined), two were children between the ages of 5 and 10, and four were between the ages of 2 and 5. But the youngest of the deceased were the twins, who were likely between 28 and 32 gestational weeks old. The elite woman was between 25 and 35 years old when she died, according to a skeletal analysis, the researchers found.

A further look at the elite woman’s bones indicated that she was cremated on a large pyre that likely burned for several hours. But when the fire extinguished, “the ashes were collected more carefully than usual (bone weight is 50% higher than average [compared with other cremated burials]) and deposited in an interesting early Vatya urn,” the researchers wrote in the study. Given that she was buried with the twin fetuses, the woman probably died from complications related to childbirth, the researchers said.

Where was she from?

The research team did a chemical analysis, which entailed looking at the different versions, or isotopes, or strontium in the deceased’s teeth and bones. Different regions have different ratios of strontium isotopes, which people absorb in the water and food they consume.

These strontium isotopes then end up in people’s bones and teeth, allowing researchers to measure and compare them with strontium isotopes found in the environment.

The vast majority of the individuals the team looked at had local strontium signatures, especially the men and children.

The elite woman, in contrast, was born elsewhere and moved to the region between the ages of 8 and 13, Cavazzuti said. Furthermore, an analysis of her grave goods revealed that the bronze neck ring and a gold ring were “prestige objects” similar to valuable items found in other burials and hoards in Central Europe, he said.

“It is not improbable that the neck-ring and pins/needles were meant to symbolize a link with her native land, whereas the gold hair-ring (a wedding gift?) embodied the new local identity she acquired by joining the [new] community at the highest rank,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Another buried woman, who did not have any grave goods, had a strontium signature from elsewhere, possibly from Lake Balaton in western Hungary or central Slovenia, the researchers noted.

Previous research has already shown that women in Europe — especially high-status ones — married outside their local communities since at least the late Neolithic or the Copper Age (about 3200 B.C. 2300 B.C.), Cavazzuti said. During the Bronze Age, societies across Europe were largely patrilocal, meaning that the men stayed in their hometowns while some women travelled from different communities to marry them.

Perhaps these marriages were crucial to the emerging elite “in order to institute or reinforce political powers and military alliances, but also to secure routes [and] economic partnerships,” Cavazzuti said.