Signs of Surgery Examined on Medieval Woman’s Skull

The skull of an early medieval woman found in Italy shows signs of two trepanations – surgeries for making holes in the head.

There were several reasons for trepanation, but in this case, the procedures seem to have been attempting to remedy an illness, researchers reported in a new study. However, they couldn’t determine exactly what that illness was.

“We suppose that this individual died from pathologies that may have been related to her condition,” Ileana Micarelli, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science. “But we are not certain about the reason.” Micarelli is the lead author of the new study, published Jan. 23 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, part of which she wrote as a doctoral student at the Sapienza University of Rome.

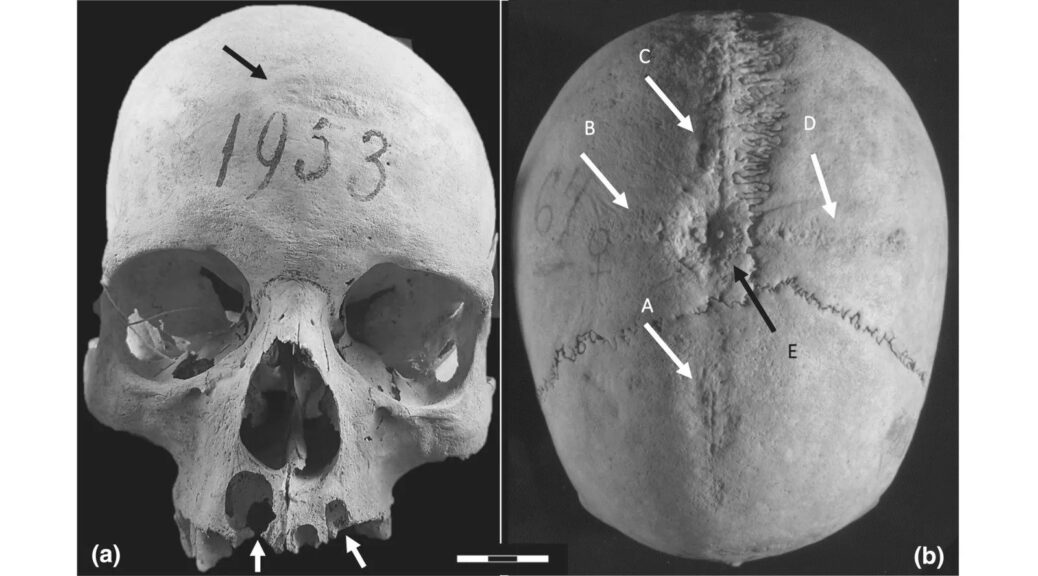

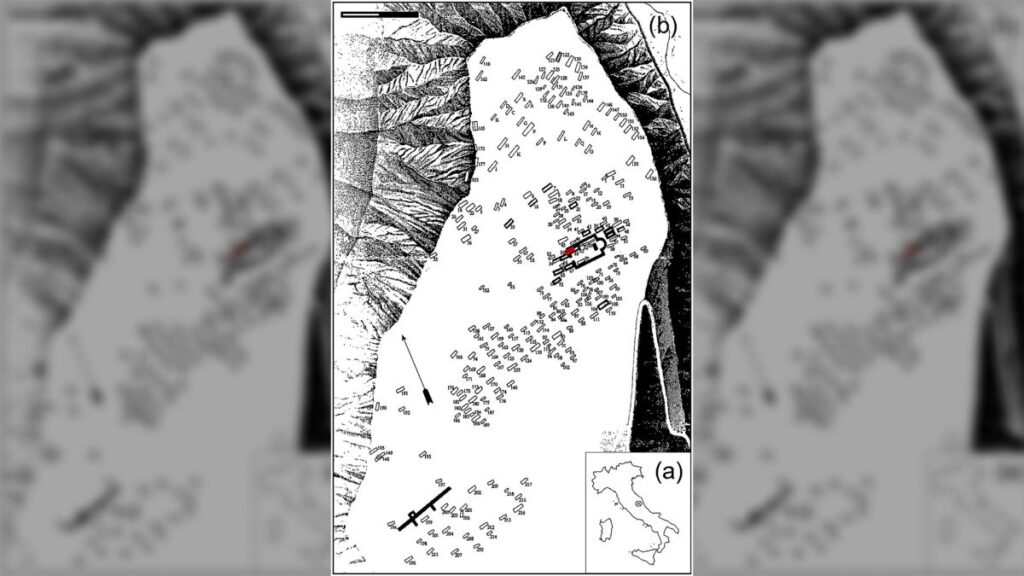

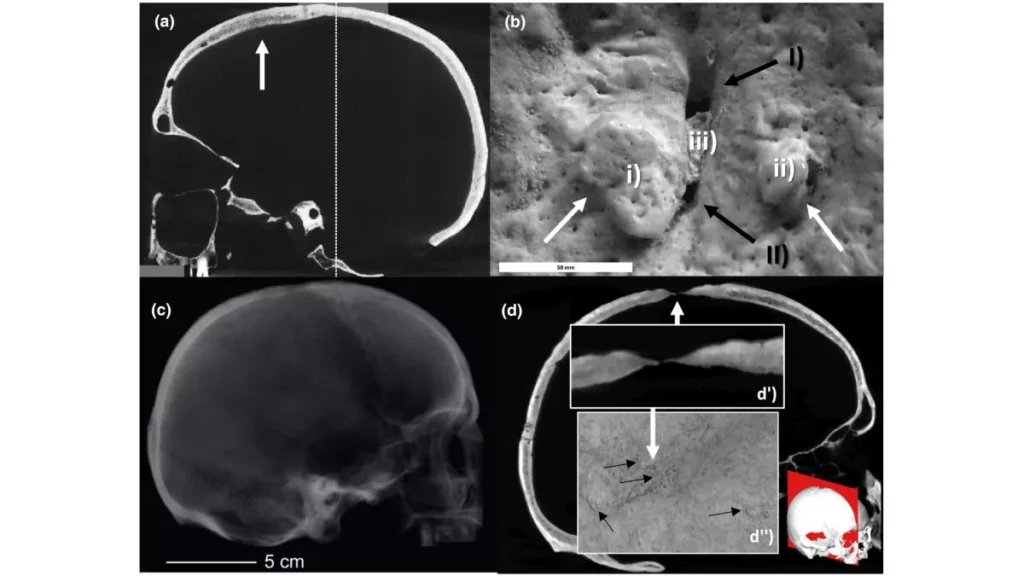

The skull’s most remarkable features, according to the study authors, are traces of a huge cross-shaped incision that show that most of the skin of the woman’s scalp was peeled back, with a partially healed oval of bone at its center that seems to be the result of a trepanation performed up to three months before she died.

Lombard castle

The woman’s skull was found in the 19th century during excavations at a cemetery at Castel Trosino in central Italy, about 80 miles (130 kilometers) northeast of Rome.

From around the sixth to eighth century A.D., Castel Trosino was a stronghold of the Lombard people — Germanic invaders who established a kingdom in Italy after the fall of the Roman Empire — and the researchers think this woman was a wealthy Lombard.

Although hundreds of burials were found during the excavations, just 19 skulls have survived. The rest of the woman’s skeleton is lost, which complicates any modern analysis, Micarelli said.

As well as the cross-shaped incision, the skull shows clear signs of a second surgery, when the bone behind the woman’s forehead was scraped thin after the skin there was peeled back. This appears to have been an attempt at a second trepanation, Micarelli said. There is also evidence that the woman died before the second procedure could be completed: The patch of scraped bone doesn’t go all the way through the skull, and there is no sign that it ever healed, Micarelli said.

But the new scientific analysis doesn’t show any reason why this woman would have voluntarily undergone both of these extreme surgeries, which must have been painful, although painkillers from plants were known of at the time, she said.

Micarelli speculated that the woman may have suffered extreme pain from two large abscesses on her upper jaw, which could have spread the infection to her brain. “We can imagine that these were quite painful as well,” she said.

Ancient Remedy

Bioarchaeologist Kent Johnson, an associate professor of anthropology at the State University of New York, Cortland who wasn’t involved in the study, said there is evidence that trepanations have been carried out for thousands of years. “The practice of trepanation is seen on almost every continent, wherever people have lived,” he told Live Science. “It’s a long-standing and pretty widespread practice.”

In most cases, trepanation was performed in an attempt to cure an ailment and mainly to alleviate trauma to the skull, such as swelling of the brain caused by a blow to the head, Johnson said. However, some scholars have suggested that the surgery sometimes had a ritual purpose.

Indeed, Micarelli and her colleagues considered that the trepanations on the Castel Trosino skull may have been performed for cultural reasons — something is seen among the Avar people in the Carpathian Basin (parts of modern-day Hungary and Romania) in the early medieval period — or as a judicial punishment. However, the study authors ruled out both of those ideas in the case of the Lombard woman’s skull.

In fact, it’s possible that the incisions were not from trepanation at all, said John Verano, an anthropologist and professor at Tulane University and author of “Holes in the Head: The Art and Archaeology of Trepanation in Ancient Peru” (Dumbarton Oaks, 2016) who wasn’t involved in the Castel Trosino research.

He suggested that what Micarelli and her colleagues interpreted as a trepanation on the top of the skull may instead have been an attempt to scrape away infected bone.

“I [have] never seen a trepanation like this, if indeed it is a trepanation,” he told Live Science in an email. “This is a complex case with multiple possible scenarios to explain the bone reaction.”