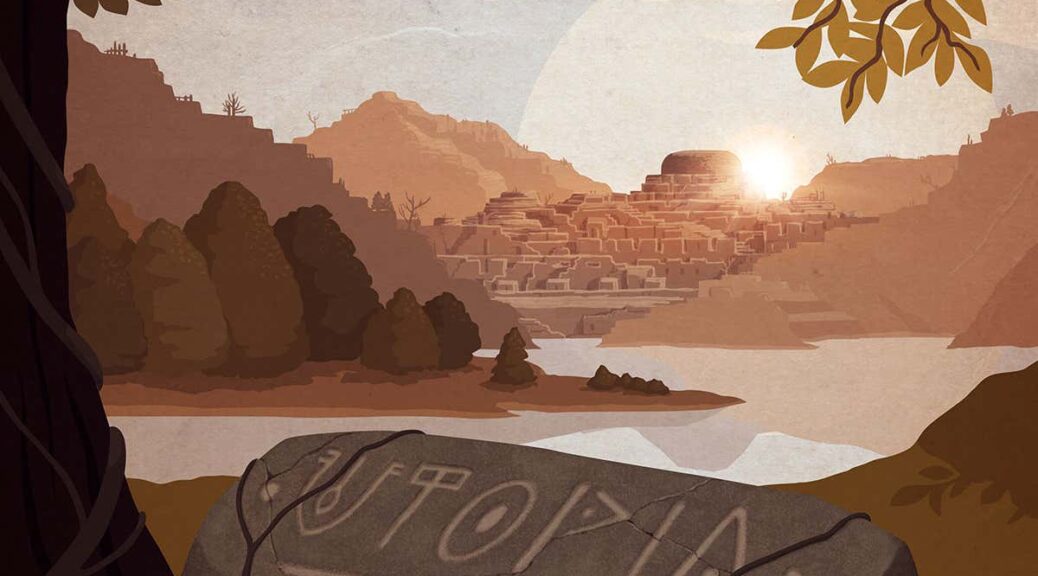

The real utopia: This ancient civilisation thrived without war

Many believe the idea of a utopian society is an impossible fantasy. But there may have been one mysterious, ancient group of people that was able to fulfil the dream of life without conflict or rulers.

Remains of the Indus civilisation, which flourished from 2600 to 1900 BC, show no clear signs of weapons, war or inequality. Many believe the idea of a utopian society is an impossible fantasy.

But there may have been one mysterious, ancient group of people that was able to fulfil the dream of life without conflict or rulers.

Remains of the Indus civilisation, which flourished from 2600 to 1900 BC, show no clear signs of weapons, war or inequality.

Robinson points out that archaeologists have uncovered just one depiction of humans fighting, and it is a partly mythical scene showing a female goddess with the horns of a goat and the body of a tiger.

There is also no evidence of horses – an animal that late became common in the region – suggesting they were not use to raid other towns and cities.

In the almost 100 years since the Indus civilisation was discovered, not a single royal palace or grand temple has been uncovered.

Speaking to Robinson, Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum, said: ‘What’s left of these great Indus cities gives us no indication of a society engaged with, or threatened by, war.

‘Is it going too far to see these Indus cities as an early, urban Utopia?’.

While Mr MacGregor sees the utopian theory as credible, others cast doubt on the total absence of war.

Richard Meadow, Director of the Zooarchaeology Laboratory at the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, said: ‘There has never been a society without conflict of greater or lesser scale.’

He argues that until the Indus script is deciphered, we cannot really know whether they lived this idyllic life. Large societies are usually overseen by a central government, yet findings suggest otherwise for the Indus civilisation.

So far, the only sculpture that might depict a ruler is of a bearded man, dubbed the ‘priest-king’ – due to his resemblance to Buddhist monks and Hindu priests.

Many of the structures and buildings, however, would have taken the coordination of tens of thousands of men, which some argue would have required a leader of sorts.

For example, Mohenjo-Daro – an archaeological site in the province of Sindh, Pakistan – required a huge amount of manpower to build.

While the Indus might sound like they lived a utopian fantasy, the civilisation mysteriously came to an end in around 1900 BC. Robinson believes the key in understanding this civilisation, is deciphering their script.

In an article published in Nature last year, he said: ‘More than 100 attempts at decipherment have been published by professional scholars and others since the 1920s.

‘Now – as a result of increased collaboration between archaeologists, linguists and experts in the digital humanities – it looks possible that the Indus script may yield some of its secrets.’