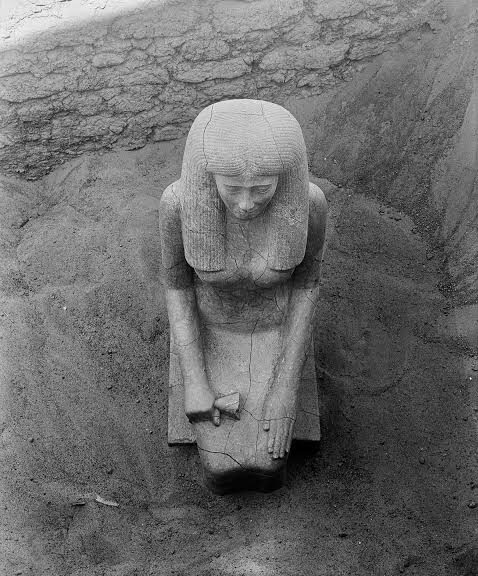

The Statue of Lady Sennuwy of Asyut Emerges from the ground at Kerma Sudan in 1913

The flourishing, wealthy empires of Nubia have lined the nile in Southern Egypt and Sudan more than a thousand years before Jesus.

A century ago, in partnership with Harvard University, the Boston archeologist George Reisner, Made an excavation in the region and brought back to the American public an enduring sight of Nubian artifacts – the largest collection of Nubian artifacts outside East Africa.

This collection was viewed today for the first time as part of a museum theme to reexamine past archeologists’ conclusions and the biases that affected their work.

The Ancient Nubia Now exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston discusses some of what Reisner, one of their own archaeologists and curators, got wrong in his representation of history.

“He is considered the father of American Egyptology,” said curator Denise Doxey. “As an archaeologist, he was really superb.”

But she says that Reisner based many of his assumptions on history that were written by Egyptians who were at war with Nubians for generations and described Nubians as barbarians.

When Reisner came across a beautifully carved, Egyptian stone statue in a tomb in Sudan in 1913, he classified the whole tomb as an Egyptian outpost — even though the statue known as Lady Sennuwy was surrounded by pottery and jewelry that was distinctly Nubian.

“He just couldn’t believe that the Nubians did all this themselves,” Doxey said. “He was a wonderful archaeologist, but he was not a forward-thinking man on social issues at all. So, he brings his own racial biases, which happened to dovetail nicely with the Egyptians’ image of the Nubians. And [it] causes them to completely misinterpret the site.”

Reisner didn’t believe that the Nubians had conquered southern Egypt for a time, and brought Lady Sennuwy back to Nubia as a prize. But Doxey says that’s what actually happened.

“In fact, he had it completely backward,” she said.

Doxey says Reisner contributed to a portrayal of Nubia as a conquered, marginalized culture somehow less important than Egypt, and eventually mostly forgotten by scholars.

“It’s a vicious cycle because people aren’t familiar with Nubia. So, museums are wary about doing exhibitions and [having] nobody come because they don’t know what Nubia is,” Doxey said. “So, it perpetuates this idea that nobody knows what Nubia is, and it helps to keep that imbalance that Egypt is somehow much more important.”

-Denise Doxey, Museum of Fine Arts, curator

“It’s a vicious cycle because people aren’t familiar with Nubia. So, museums are wary about doing exhibitions and [having] nobody come because they don’t know what Nubia is,” Doxey said. “So, it perpetuates this idea that nobody knows what Nubia is, and it helps to keep that imbalance that Egypt is somehow much more important.”

But it’s been clear for some time that Reisner got it wrong. French and Swiss teams did excavations in Sudan in the 1960s and 1970s and discovered that tomb Reisner found with the Lady Sennuwy statue was part of a thriving, Nubian metropolis at the center of a trading network that reached far into Africa.

“It’s a massive, fortified city with suburbs outside and ports and industrial areas and temples,” Doxey said. “So, it was actually a very powerful and important kingdom.”

A kingdom that left behind fine pottery that is eggshell thin and dipped in a distinctive translucent blue glaze; and gold jewelry, and sculptures depicting animals such as rams and lions. Items that were ahead of their time, and are possibly evidence of an advanced culture.

That reminds some people of Wakanda, the fictional, ultra-advanced African country in the movie, “Black Panther.” Ta-Nehisi Coates, who writes the “Black Panther” series for Marvel, has said he imagines Wakanda being pretty much where Nubia was.

In a video in the Nubia exhibit, Nicole Aljoe, director of Africana studies at Northeastern University, talks about Pauline Hopkins, an African American writer who, in 1902-1903, wrote a serialized novel, “Of One Blood; Or, The Hidden Self,” in which one of the main characters discovers a secret, advanced society of superhumans in the Nubia region.

“It is fascinating — it’s this weird kind of proto-science fiction, fantastic, but at the same time supernatural presentation that resonated a lot for me and my students with the film [“Black Panther”] after it came out,” Aljoe said. “It’d be really cool if she was prescient in that way.”

Aljoe says the book is just one example of how African American artists have used the idea of Nubia as a symbol again and again. There were Nubian references during the Harlem Renaissance, the Black arts movement, and in rap music and the Black Lives Matter movement, she says. Right now, there’s a ballot measure in Boston to rename a historic spot Nubian Square. It’s currently named for Thomas Dudley, a governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony who signed laws that enabled the slave trade.

“So, Nubia as kind of representing a royal African history that folks can use to challenge European and racist colonial ideologies,” Aljoe said.