2,000-Year-Old Skeleton of Sarmatian Man Identified in England

How did a young man born 2,000 years ago near what is now southern Russia, end up in the English countryside?

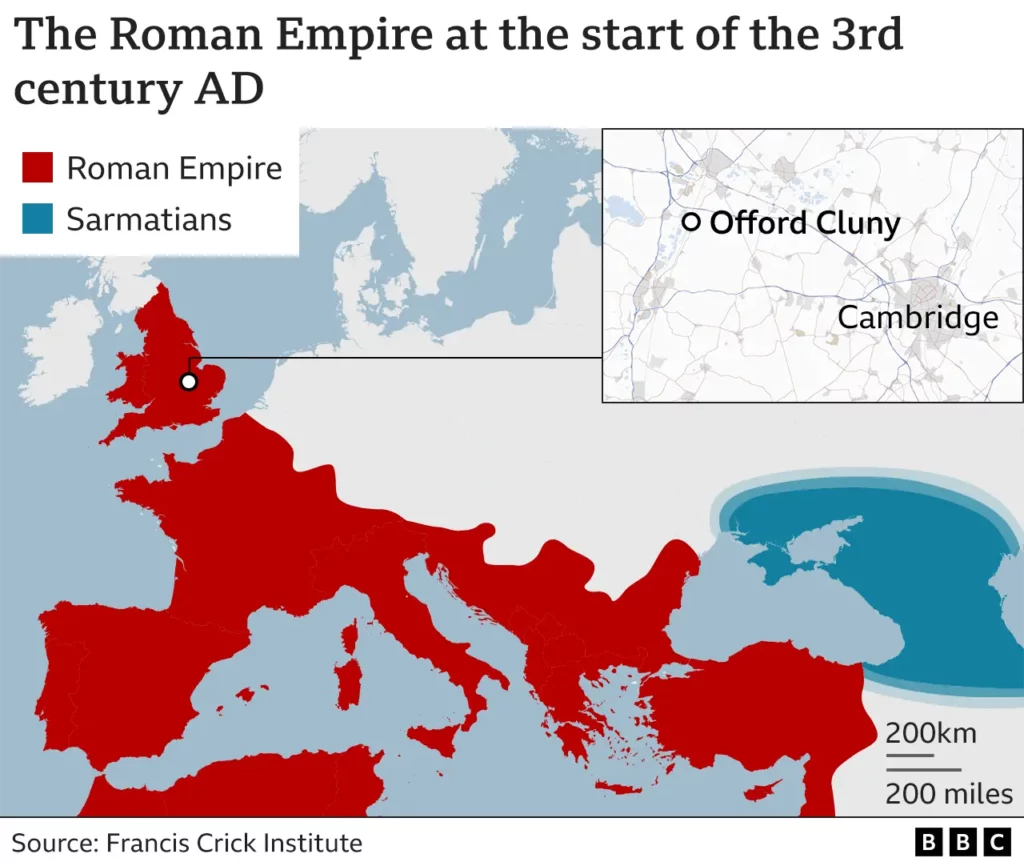

DNA sleuths have retraced his steps while shedding light on a key episode in the history of Roman Britain. Research shows that the skeleton found in Cambridgeshire is of a man from a nomadic group known as Sarmatians. It is the first biological proof that these people came to Britain from the furthest reaches of the Roman empire and that some lived in the countryside.

The remains were discovered during excavations to improve the A14 road between Cambridge and Huntingdon. The scientific techniques used will help reveal the usually untold stories of ordinary people behind great historical events.

They include reading the genetic code in fossilised bone fragments that are hundreds of thousands of years old, which shows an individual’s ethnic origin.

Archaeologists discovered a complete, well-preserved skeleton of a man, they named Offord Cluny 203645 – a combination of the Cambridgeshire village he was found in and his specimen number. He was buried by himself without any personal possessions in a ditch, so there was little to go on to establish his identity.

Dr Marina Silva of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute, in London, extracted and decoded Offord’s ancient DNA from a tiny bone taken from his inner ear, which was the best preserved part of the entire skeleton.

“This is not like testing the DNA of someone who is alive,” she explained.

“The DNA is very fragmented and damaged. However, we were able to (decode) enough of it.

“The first thing we saw was that genetically he was very different to the other Romano-British individuals studied so far.”

The latest ancient DNA analysis methods are now able to flesh out the human stories behind events that, until recently, have been reconstructed only by documents and archaeological evidence.

These largely tell the tales of the wealthy and powerful.

The latest research is a detective story which uses cutting edge forensic science to unravel the mystery of an ordinary person – a young man buried in a ditch in Cambridgeshire between 126 and 228 AD, during the Roman occupation of Britain.

At first, archaeologists thought Offord to be an unremarkable discovery of a local man. But DNA analysis at Dr Silva’s lab showed that he was from the furthest reaches of the Roman Empire, an area that is currently southern Russia, Armenia, and Ukraine. The analysis showed him to be a Sarmatian, who are Iranian-speaking people, renowned for their horse-riding skills.

So how did he end up in a sleepy backwater of the empire so far from home?

To find the answers, a team from the archaeology department of Durham University used another exciting analysis technique to examine his fossilised teeth, which have chemical traces of what he ate.

Teeth develop over time, so just like tree rings, each layer records a snapshot of the chemicals that surrounded them at that moment in time. The analysis showed that until the age of six he ate millets and sorghum grains, known scientifically as C4 crops, which are plentiful in the region where Sarmatians were known to have lived.

But over time, analysis showed a gradual decrease in his consumption of these grains and more wheat, found in western Europe, according to Prof Janet Montgomery.

“The (analysis) tells us that he, and not his ancestors, made the journey to Britain. As he grew up, he migrated west, and these plants disappeared from his diet.”

Historical records indicate that Offord could have been a cavalry man’s son, or possibly his slave. They show that around the time he lived, a unit of the Sarmatian cavalry incorporated into the Roman army was posted to Britain.

The DNA evidence confirms this picture, according to Dr Alex Smith of MOLA Headland Infrastructure, the company that led the excavation.

“This is the first biological evidence,” he told BBC News.

“The availability of these DNA and chemical analysis techniques means that we can now ask different questions and look at how societies formed, their make-up and how they evolved in the Roman period.

“It suggests that there was much greater movement, not just in the cities but also the countryside.”

Dr Pontus Skoglund, who heads the ancient genomics laboratory at the Crick, told BBC News that the new technology is transforming our understanding of the past.

“The main impact of ancient DNA to date has been improving our understanding of the Stone and Bronze Ages, but with better techniques, we are also starting to transform our understanding of the Roman and later periods.”

The details have been published in the journal, Current Biology.