A mummy discovered in a vast burial ground of Egypt’s pharaohs could change how ancient history is understood

A new analysis of an ancient Egyptian mummy suggests that advanced mummification techniques were used 1,000 years earlier than previously believed, rewriting the understood history of ancient Egyptian funerary practices.

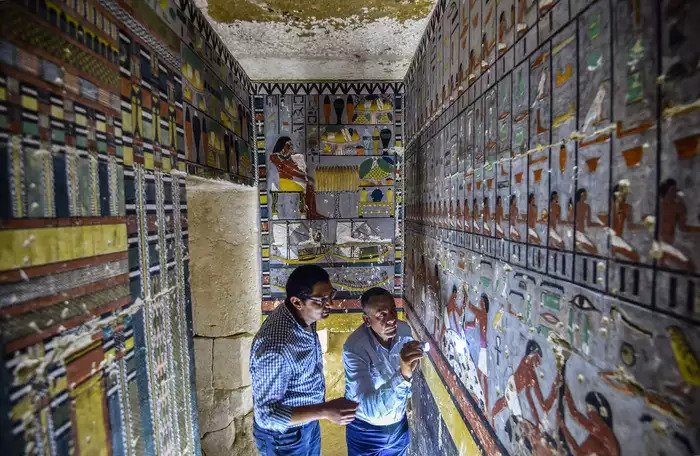

The discovery centres around a mummy, known as Khuwy, believed to have been a high-ranking nobleman. He was excavated at the necropolis, a vast ancient burial ground of Egyptian pharaohs and royals near Cairo, in 2019.

Scientists now believe that Khuwy is much older than previously thought, dating back to Egypt’s Old Kingdom, which would make him one of the oldest Egyptian mummies ever to be discovered, The Observer reported.

The Old Kingdom spanned 2,700 to 2,200 B.C.E and was known as the “Age of the Pyramid Builders.”

Khuwy was embalmed using advanced techniques thought to have been developed much later. His skin was preserved using expensive resins made from tree sap, and his body was impregnated with resins and bound with high-quality linen dressings.

The new analysis suggests that ancient Egyptians living around 4,000 years ago were carrying out sophisticated burials.

“This would completely turn our understanding of the evolution of mummification on its head,” Professor Salima Ikram, head of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told The Observer.

“If this is indeed an Old Kingdom mummy, all books about mummification and the history of the Old Kingdom will need to be revised.”

“Until now, we had thought that Old Kingdom mummification was relatively simple, with basic desiccation – not always successful – no removal of the brain, and only occasional removal of the internal organs,” Ikram told The Observer. Ikram was surprised by the amount of resin used to preserve the mummy, which is not often recorded in mummies from the Old Kingdom.

She added that typically more attention was paid to the exterior appearance of the deceased than the interior.

“This mummy is awash with resins and textiles and gives a completely different impression of mummification. In fact, it is more like mummies found 1,000 years later,” she said.

Ikram told The National that the resin used would have been imported from the Near East, most likely Lebanon, demonstrating that trade with neighbouring empires around that time was more extensive than previously thought.

The discovery has been documented in National Geographic’s new series, Lost Treasures of Egypt, which starts airing on 7 November. Tom Cook, who produced the series for Windfall Films, told The Observer that Ikram initially could not believe that Khuwy dated back to the Old Kingdom because of the advanced mummification techniques.

“They knew the pottery in the tomb was the Old Kingdom but [Ikram] didn’t think that the mummy was from [that period] because it was preserved too well,” Cook told the outlet.

“But over the course of the investigation, she started to come round [to the idea].”

Khuwy’s ornate tomb featured hieroglyphics that suggested the burial took place during the Fifth Dynasty period, spanning the early 25th to mid-24th century B.C.E, The Smithsonian said.

Archaeologists also found pottery and jars used to store body parts during the mummification process that dated back to that time.

Ikram’s team will conduct more tests to confirm that the remains do belong to Khuwy.

She told The National that one possibility was that another person could have been mummified and buried centuries later in a re-purposing of the tomb.

“I remain hesitant until we can conduct carbon-14 dating,” Ikram told the outlet, adding that it would likely take six to eight months.