Archaeologists unearth the remains of three dozen headless people at a stone age settlement in Vráble, Slovakia

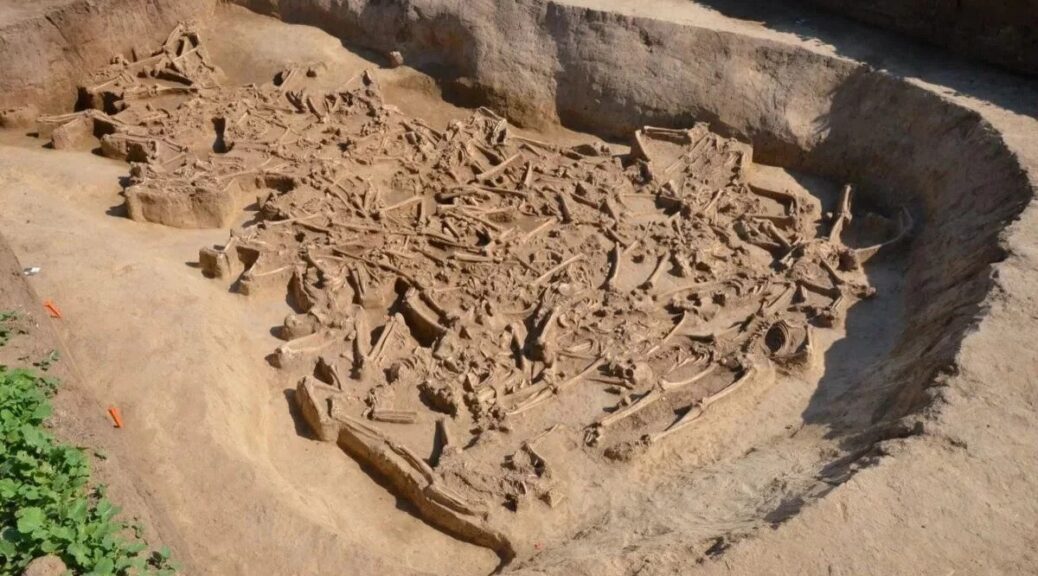

Archaeologists have unearthed a mass grave containing the remains of about three dozen headless bodies of people at a settlement dated 5250-4950 BC in Vráble, western Slovakia.

The team of Slovak-German archaeologists investigating one of the largest Central European Stone Age settlements at Vráble thinks these people may have been killed in cult ceremonies.

The skeletons were found inside a defensive ditch of one of the largest Neolithic settlements in Central Europe.

Three settlement areas cover more than 120 acres in the Neolithic settlement. Over the last seven years, excavations and geophysical surveys have revealed more than 300 long houses in the settlement, albeit built at different stages of occupation.

Archaeologists estimate that 50-70 houses were in use at any given time.

One of the three settlement areas was fortified with at least one defensive ditch and a palisade during the final phase of occupation.

The settlement has six entrances through the defensive perimeters. Individual graves have been discovered in and around the ditch during previous excavations.

This year, skeletal remains of at least 35 people were discovered in a lengthy ditch close to one of the settlement’s entrances. The bodies seem to have been thrown in randomly. They were discovered with their arms and legs extended, lying on their sides, backs, and stomachs.

The grave contained the remains of men, women, and children, many of whom were adolescents and young adults when they passed away. Peri-mortem fractures do exist. The skull of one child and one mandible were the only bones from heads found in the grave.

Experts will also look for any genetic links between them, and whether the heads were forcibly removed or separation occurred only after the decomposition of the body.

“Only then will we be able to answer several questions about the social categorization of the [site’s] inhabitants, probably also about the emerging social inequality in the conditions of early agricultural societies, and perhaps even reconstruct the functioning or the causes of the demise of this vast settlement,” the director of the archaeological institute Matej Ruttkay said.

The researchers said some of their other findings about the settlement have been exceptional.

“In the final stage of operation, one of the areas was fortified with a moat with six entrances to the settlement, which was doubled by a palisade. This was absolutely exceptional in Central Europe at that time,” explains Ivan Cheben, head of archaeological research at SAV.

“We also confirmed the presence of more than 300 longhouses through a detailed geophysical survey. It is possible that 50 to 70 houses could have been used at the same time in the individual stages of the settlement’s functioning.”